The lessons of Srebrenica: ‘it can happen again’

Never again. That was the predominant feeling in Europe after World War II. But in 1995, there was Srebrenica, a new genocide on European territory. A group of Social Geography students from Radboud University travelled to Srebrenica. Their teacher warns: 'History might repeat itself.'

Prefer to read this story in Dutch?

The soul of the town of Srebrenica did not survive the 1995 genocide: a total of 8,000 people were murdered during this tragedy, which took place during the Bosnian War. Families were torn apart, and many of those who managed to escape the violence never returned. They are afraid to, or don’t have the money to do so. All that is left is a silent little town. Dimly lit houses stand side by side with broken houses without windows, empty carcasses that only remind us of what Srebrenica used to be: a rich mountain town in the heart of Yugoslavia.

Korthals Altes is one of the Nijmegen students from the Master’s in Conflicts, Territories and Identities, a programme which falls under Human Geography. The group is visiting Bosnia and Herzegovina for a week, to see with their own eyes what war can lead to. He has been in Srebrenica before, he explains, so he knew what to expect. Which is more than can be said for Benthe Guezen (23): ‘What I feel mostly is incredulity: How could something like this happen? Things should have gone differently. It makes me really angry.’

Srebrenica is a black page not only in the history of Bosnia and Herzegovina, but also in that of the Netherlands. Under the flag of the United Nations, the Dutch army had boots on the ground in Srebrenica to protect the local Muslim population against the advancing Bosnian Serb army. When the Serbians tanks entered the neutral enclave of Srebrenica, the Dutch, with their light weapons, were utterly helpless to stop them. In front of their eyes, thousands of Muslims were deported to be systematically murdered.

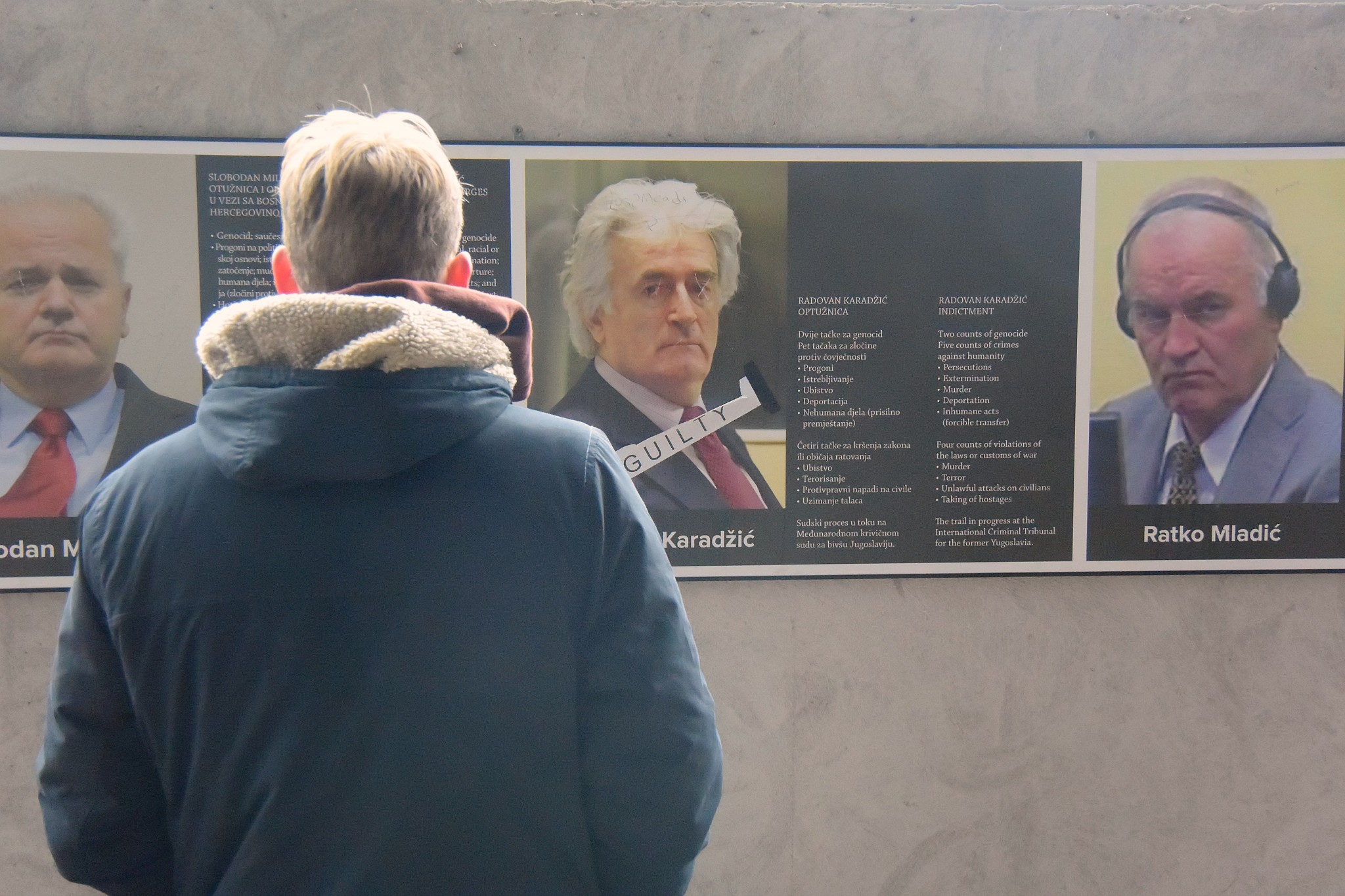

Opposite the cemetery, on the other side of the road, is the former battery factory that functioned during the war as the base for Dutchbat, the Dutch battalion. The empty factory hall is now an exhibition and memorial space, where the Dutch do not strike a particularly flattering figure. One of the photographs shows Dutchbat commander Thom Karremans having a drink in Srebrenica with General Ratko Mladic of the Bosnian-Serbian troops. Mladic is often referred to as ‘the butcher of Srebrenica’. In the factory hall, visitors can read racist texts left behind by the Dutch soldiers: No teeth…? A moustache…? Smells like shit…? Bosnian girl!

Guezen: ‘I was afraid beforehand that I would feel guilty visiting Srebrenica. Which is strange, in a way, since I personally had nothing to do with what happened here. But these were Dutch people!’

Divided

The Bosnian war raged until 1995 and left deep scars on the country. The Bosnia and Herzegovina of today is home to the three ethnic groups that fought in the war: Bosnian Muslims (also known as Bosniaks), Bosnian Serbs and Croats. Relations between these groups are still very tense. ‘The country is strongly divided,’ says anthropologist and conflict expert Mathijs van Leeuwen, who accompanies the students on this trip, together with political geographer Henk van Houtum. ‘Take the capital city, Sarajevo, where the three ethnic groups used to live all together. After the war the city became strongly segregated: it is now inhabited almost solely by Muslims. The Serbs have moved away.’

Bosnia is slowly changing, says Van Leeuwen. Too slowly, according to many inhabitants. ‘There is so much unemployment. Citizens have little faith in their politicians, who are obsessed with ethnic differences and fail to address the real problems. This has a paralysing effect on politics. Mutual distrust dominates.’

Bosnian society is based on ethnic differences. After the 1995 Peace Treaty, Bosnia and Herzegovina was divided into two parts: one part where Serbs form a majority and one part mostly inhabited by Bosnian Muslims and Croats. The former front line forms the border between these two regions. The country has not one, but three Presidents, one for each ethnic group. In the last population census, Bosnians had to indicate to which group they belong: there was no general ‘Bosnian’ option on the form. Van Leeuwen: ‘Since the end of the war, the ethnic segregation has become institutionalised, and therefore even more apparent.’

Aleppo

Comparisons have recently repeatedly been drawn between Srebrenica and a more recent stage of war violence: Aleppo. For example, Dutch Minister of Foreign Affairs Bert Koenders has warned that Aleppo is threatening to become the ‘Srebrenica of today’.

Political Geographer Henk van Houtum strolls between the graves of the Srebrenica cemetery. He understands why Koenders would draw such a comparison. ‘Of course he has political reasons for saying it. He is using it to bring attention to the failure of the international community respond, just as was the case during the Fall of Srebrenica.’ There are more parallels to be drawn between the Balkan Wars and today’s war in Syria. ‘In the 1990s too, we had a refugee camp in Heumensoord near Nijmegen. At the time it was filled with Yugoslavs.’

‘It’s still important to realise that this place only tells one side of the story.’

At the same time, Koenders is not telling the entire story. According to Van Houtum he is using the Srebrenica comparison to wake us up and draw our attention to Aleppo, where Assad’s regime is joining Putin’s Russia. ‘But Koenders is ignoring the role played by the entire international community in the war in Syria.’ After all: the West played a role in the escalation in Syria. ‘The US invaded Iraq under false pretences, thereby contributing to extremism in the region. A number of European states are selling weapons to Saudi Arabia, which they in turn pass on to Syrian hands.’

The thick layer of snow on the Srebrenica cemetery is untouched: this is not a place that attracts many visitors, despite the scale of the disaster. Van Houtum has his own perspective on the cemetery. ‘This place is a symbol for commemorating the dead; it makes me go quiet inside. At the same time, I walk around here and ask myself: ‘What story is being told here?’’

According to Van Houtum, it is the task of researchers to view a conflict from a number of perspectives, so that they can show the bigger picture. ‘Commemorative places such as this are very important as permanent reminders of a terrible genocide. But it is also important to zoom out: to the conflict as a whole, and the interests that played a role in it. The Bosnian War was very complex. It’s still important to realise that this place only tells one side of the story.’

Part of the Srebrenica story is that the Dutch soldiers failed, that they did not show respect to the people they were supposed to protect. ‘This is very understandable coming from the Muslims’ perspective,’ says Van Houtum. ‘But the Dutch could not have prevented the genocide. They were too lightly armed and waited in vain for international support. The Serbs were the ones who committed the genocide, not the Dutch. And the Serbs were only reacting, as they would have put it, to the murders committed by Bosnian Muslims elsewhere.’

Doom scenario

If there is something to be learnt from Srebrenica and Syria, it is that wars are rarely local events, but often intertwined with developments of an international scale. Although the Bosnian War ended more than twenty years ago, these international influences still affect us today. Bosnia and Herzegovina is still the subject of international wrangling between parties such as the European Union, Croatia, Serbia, Turkey, and Russia. As of 2016, the European Union still has troops on the ground in Bosnia and Herzegovina to ensure that the 1995 Peace Treaty is respected.

And this is necessary, says Van Houtum. He sketches a doom scenario: ‘Imagine that the extreme right comes to power in France this year. That might mean the end of the European Union, and therefore the end of the peace mission in this region. The Serbs in Bosnia might make use of this moment to join Serbia. What would happen then? History might just repeat itself.’

This shows that safety and peace on European territory is by no means obvious. ‘The ball can also start rolling in the wrong direction. Here in Srebrenica we see what the consequences of that might be. This really could happen again.’

Student Benthe Guezen hopes that this doom scenario will not materialise, and that the Bosnian population will seek contact with one other. Her visit to Srebrenica has not made her more optimistic. As the bus carries the students over the snow-covered mountains back to their Sarajevo hotel, she talks about the new generation of Bosnians, growing up in their own separate world: ‘The Muslims, Croats and Serbs all have their own schools, because the teachers cannot agree on a common history curriculum. If even the children are separated and live in their own reality, how can Bosnia ever become a single country again?’ / Photo’s: Margriet Rozema and Mathijs Noij

[kader-xl]

The Bosnian war in short

The Bosnian war in short

In the 1990s, Yugoslavia completely fell apart. Slovenia and Croatia declared their independence in 1991, and the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina organised a referendum to poll its population on independence. Bosnian Croats and Bosnian Muslims mostly voted for independence. Bosnian Serbs were against: they wanted to remain with ‘Belgrade’ and boycotted the referendum.

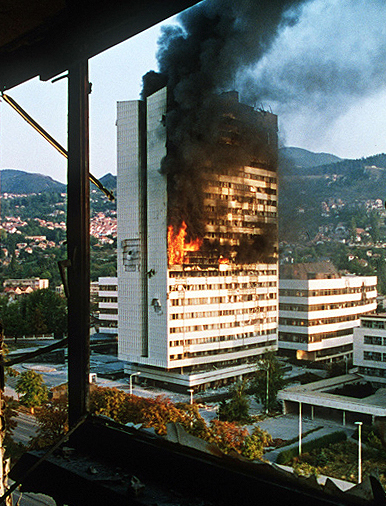

The referendum ended with a ‘yes’, following which Bosnia and Herzegovina declared its independence. In response, the Bosnian Serbs declared their own Serb Republic (Republika Srpska), in which they formed the majority. Throughout the country, fights quickly erupted between Bosnian Serbs and Bosnian Muslims. Sarajevo was surrounded by Serbs: the siege of Sarajevo began. The Serbs could count on support from Belgrade.

In June 1992, the United Nations expanded their peace mission in former Yugoslavia and positioned troops on Bosnian territory. Due to a limited mandate, this mission was unable to stop the war. Under increasing pressure from the international community, the warring parties signed a peace treaty on 14 December 1995. The Treaty of Dayton divided Bosnia and Herzegovina into two regions, one for the Muslims and the Croats, and the other for the Serbs. This peace treaty is still valid today.

In the 1990s more than 2 million Bosnians fled the war in their region. Some remained in former Yugoslavia, while others fled to Western Europe. The Netherlands took in approximately 25,000 Bosnian refugees.

[/kader-xl]

eee schreef op 27 januari 2017 om 20:14

Bosniaks have a ethnic name and it is Bosniak (Bosniaks in plural) and not “muslim”.