Behind the walls of a gated community: ‘The dystopian image of a hermetically sealed stronghold is often misguided’

-

Beeld: Weidner/Flickr

Beeld: Weidner/Flickr

Scared rich people, living their privileged lives behind a safe fence. That is the image many people have of gated communities. Social geographer Simone Pekelsma personally spent weeks living behind the walls of two secure housing communities and emerged with a very different story.

In recent decades, millions of gated communities have been built around the world. The rise of these walled-in residential communities has been a hot topic among social scientists for years. After all, aren’t these communities an outgrowth of the increasingly extreme gap between rich and poor? After all, the predominant image of this form of cohabitation is that of affluent city dwellers shutting themselves off from the ‘unsafe’ outside world.

Social geographer Simone Pekelsma also became fascinated by this topic. In the context of a documentary, she conducted research on gated communities in Istanbul back in 2011. ‘I visited several gated housing estates there and it soon struck me that the ideas I had from academic literature – hermetically sealed and only for the rich – did not match reality,’ says Pekelsma.

‘I was actually really curious about life inside those walls’

She also noticed that the descriptions in the literature mostly focused on the external form. ‘They were about the fences or walls, or about the barriers and security guards. Or about the slick image developers painted of these complexes in their sales catalogues. I was actually more curious about life inside those walls. Why do people decide to live in a gated community and how do they experience life there?’

Unable to find any answers to these questions in the academic literature, Pekelsma decided to find out for herself. The documentary she collaborated on ultimately failed to materialise, but Pekelsma was awarded a PhD for her scientific research this month.

High-rise

Not all gated communities are sealed off from the outside world, as the social geographer soon discovered. ‘In several of the communities I lived in, for example, I could just rent a flat through Airbnb,’ says Pekelsma. She studied two gated communities from the inside – one in Madrid and one in Istanbul – by living there for several weeks with her family. ‘That was also partly strategic: I thought that if I went there with my family, it might be easier to get access to people.’ Her strategy worked, and Pekelsma spoke to many different residents. In the following years, she visited the communities several more times for shorter periods.

‘The simple academic definition of a gated community – a residential complex with a fence or wall around it and a barrier where access is managed by a human guard – does not do justice to the diversity among this type of community,’ says Pekelsma.

‘Of course, some communities do match the textbook example of the somewhat luxurious detached houses in a park-like setting with a fence around it. But there are also a lot of forms of high-rise buildings these days. Especially in big cities in Thailand, India and China, among others, these are very much on the rise. In Istanbul, there is even a gated community with 60,000 residents.’

Just looking at the differences between the two projects in Istanbul and Madrid, you can see that communities can be very different, says Pekelsma. ‘In Spain, for example, it is quite normal to move to a gated community as soon as you have children,’ says Pekelsma. ‘It is so natural there that people are not even aware of the fact that they live in a gated community. Many people grew up in one themselves. These communities are not only there for the highest earners, but also for the lower middle class.’

Child-friendly

An apartment complex where people live around a park with a swimming pool and perhaps a playground or padel court, that is what a prototypical residential project in Madrid looks like. With a security guard at the entrance keeping an eye on who is entering and leaving.’

‘Almost everyone I spoke to in Madrid said, “we live here because of the children and once they grow up we may move away”. Before having children, people tend to live in the city centre, but with children it becomes too crowded, too hot, and too cramped in summer. A gated community is first and foremost a really nice place for children to grow up, there is a sense of community, and it is good to spend summers next to the pool.’

‘You can put up fences, but you have no control over what residents bring in themselves’

In the complex where Pekelsma stayed in Istanbul, a high-rise residential tower, she found far more diversity than she had expected based on the academic literature. ‘That really surprised me. Almost 65% of the units were rental properties, and the residents came from different walks of life, from athletes who wanted to live close to the big nearby stadium, to men who kept an apartment to meet their mistress. There were students, families, and I even heard that members of the mafia retreated there occasionally.’

What surprised her most were the irritations and concerns residents shared with her. ‘These were not at all about the dangerous outside world full of scary poor people against whom they tried to protect themselves with a fence,’ says Pekelsma.

‘What they found most irritating, for example, were the single men who were quite loud with the girlfriends they brought along. Or the dogs people brought to the pool, or the noisy student parties. So you can put up fences or walls, but you have no control over what residents bring in themselves.’

Property marketers

Pekelsma believes one of the reasons many people find it appealing to live in a more controlled environment is the rapid growth of many cities worldwide. ‘Istanbul had approximately one million inhabitants in 1950; today it is 16 million. For a city growing that fast, it is hard to maintain facilities such as parks, car parks, playgrounds, and sports facilities. In such cases, gated communities can provide a solution.’

Many people in these megacities are also looking for a sense of community. ‘Real estate marketers in Istanbul are very clearly playing on that sentiment, with slogans like: “here you still know your neighbours” or “here you can live like in the olden days”.’

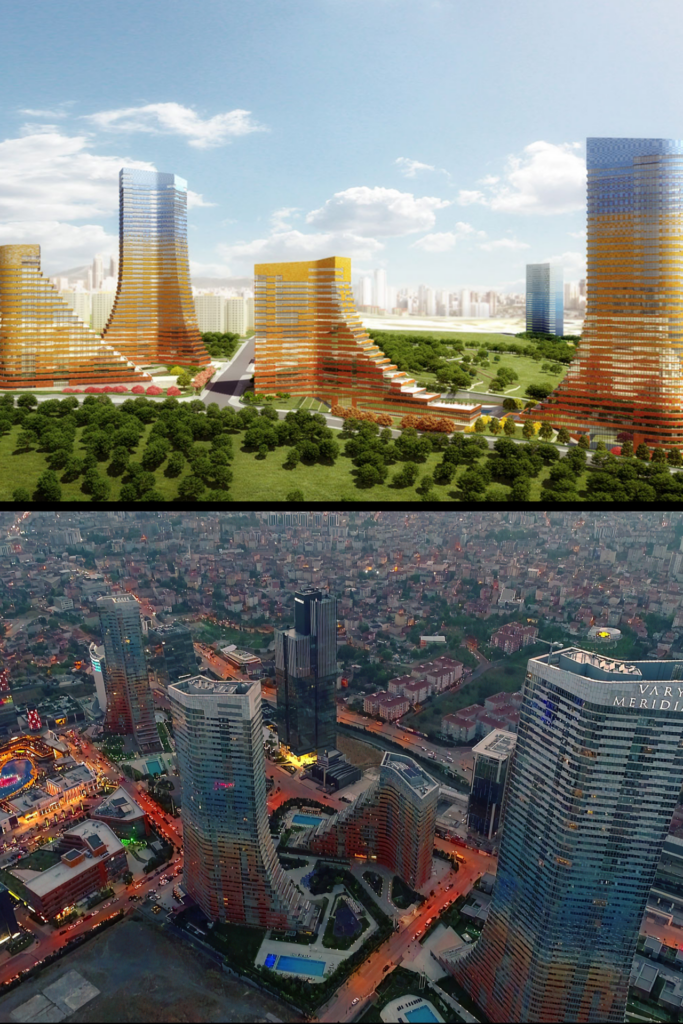

The image residents have beforehand of life in the gated community is often a lot more idyllic than the reality. ‘The image property marketers paint of super clean towers, with green trees around them, is very different from what this kind of project looks like in the reality of a big city. This often leads to disappointment.’

According to Pekelsma, many assumptions in the media and academia about gated communities arise from these slick images created by project developers. ‘To experience the reality of these communities, you have to make the effort to look behind the walls.’

Pekelsma hopes that her research can contribute to a more diverse and realistic picture of gated communities. ‘I am not saying: fill the cities to the brim with walled complexes and everything will be great. But I do want to nuance the dystopian image of hermetically sealed strongholds full of rich people. That is much too extreme.’

‘I also think that we have these same walls in our own society. Maybe not physically, but we too are facing increasing segregation, with more and more people living and functioning mainly within their own bubble.’