Brother and former Radboud student Stefan Ansinger is blissfully happy at the monastery

-

Broeder Stefan Ansinger bij het dominicanenklooster. Foto: Erik van 't Hullenaar

Broeder Stefan Ansinger bij het dominicanenklooster. Foto: Erik van 't Hullenaar

From celebrating mass to editing YouTube videos and from singing Gregorian chants to a motorcycle blessing. For Stefan Ansinger, no two days are the same. After studying Public Administration in Nijmegen, he entered the Dominican Order. Vox followed him for 24 hours in Fribourg, Switzerland, where he spent the past five years living in a monastery and studying theology.

Tuesday, 2 p.m.

In a brass bucket of consecrated water, Brother Stefan Ansinger (28) dips a brush that looks remarkably like a toilet brush. He holds it in the air, pronounces a blessing in French, and swings it down with a jerk.

The director of a Swiss real estate company and his new motorcycle get the full brunt of it. Moments later, the 15 staff members gathered in a circle around the red Ducati are also sprayed with quite a few drops of water. Everyone laughs.

This interview is part of Vox’s interview special, which can be found in the Vox stands on campus, starting next week. The magazine contains interviews with student and NEC player Dirk Proper; researcher Samira Azabar; virologist Marc van Ranst; producer Tom Verstappen; doctor Tanya Bisseling and her student daughter Jasmijn Olde; friar Stefan Ansinger; and influencer Manon van den Bos.

‘People do need to get a bit wet,’ Ansinger says a little later over coffee with Nidelkuchen, traditional pastries from Fribourg. The director and his staff hang on his every word. Ansinger explains that the blessing did not give the motorcycle any special powers, but rather blessed the person riding it.

For five years, Ansinger has lived in Fribourg, Switzerland, where he studies theology at the local university. From 2013 to 2017, the Venray-born brother studied Public Administration at Radboud University.

Ansinger met the motorcycle-riding real estate agent last spring during a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. The man in question, Vincent Hayoz, is President of the Section Suisse Romande of the Knights of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem, an order for lay people within the Catholic Church. ‘Last week he sent me a message asking me whether I was willing to bless his new bike, and here I am,’ says Ansinger. ‘And so it is that every day of a Dominican’s life looks different.’

‘I asked Stefan because he’s a young, promising brother,’ says Hayoz. ‘He will be a bishop one day, maybe even Pope,’ he says with a smile. ‘Why? Because he doesn’t want to. And anyone who doesn’t want to ends up becoming it. That’s how it goes in the Church.’

Before the brother walks back to the monastery, Hayoz gives him an envelope containing some money. ‘We’ll divide it among our fellow brothers,’ says Ansinger.

Monday, 5 p.m.

On the previous day, Brother Ansinger welcomed the Vox editor and photographer at the Couvent Saint-Hyacinthe, a nineteenth-century building in a neighbourhood with lots of modern concrete architecture. At first glance, the building doesn’t look like a monastery. Since 1921, it has mostly housed students of the Dominican Order who study theology at the University of Fribourg. Just like Stefan Ansinger. One more essay and he will have completed his study programme; he plans to return to the Netherlands in September.

The former Radboud student grew up in a Catholic family of six in Venray, on the border of Limburg and North Brabant, an area he refers to as Limbrant. ‘There is still a real Catholic culture there, with lots of conviviality and good vlaai pastries.’ His mother led a church choir, his father taught Bible studies, the six children went to church every Sunday – and are all still religious to this day.

Already at age 12, the Church was more than a weekly outing for Ansinger; he says he was struck early on by the beauty of the liturgy. ‘The way the entire congregation sings the Credo together – you just know these aren’t empty words,’ he says. ‘It was then that something clicked for me: I want to devote my entire life to this.’

As he wanted to get acquainted with the outside world first, Ansinger chose to study Public Administration at Radboud University after completing secondary school. ‘Because of the political and multidisciplinary dimension,’ he says. ‘It’s useful in the Church, where you meet people from all sorts of backgrounds.’ He travelled to campus on the Arriva train every day; at home, he served mass several times a week.

But Ansinger also lived a student life. As President of Catholic Students Nijmegen (KSN), he attended drinks to celebrate the new board wearing a suit. If he missed the last train, he spent the night with fellow students. He also occasionally visited the Molenstraat, although he was never a real party animal. ‘Just give me a beer with some bitterballen on a terrace.’

‘You have to make do with what you are given’

In a group with fellow religious students, Ansinger talked about their common vocation to the priesthood. But the diocesan seminaries in the Netherlands he visited during his studies did not appeal to him – he found them too far-removed from the world. Through a conversation with student chaplain Jos Geelen, he eventually arrived at the Dominicans.

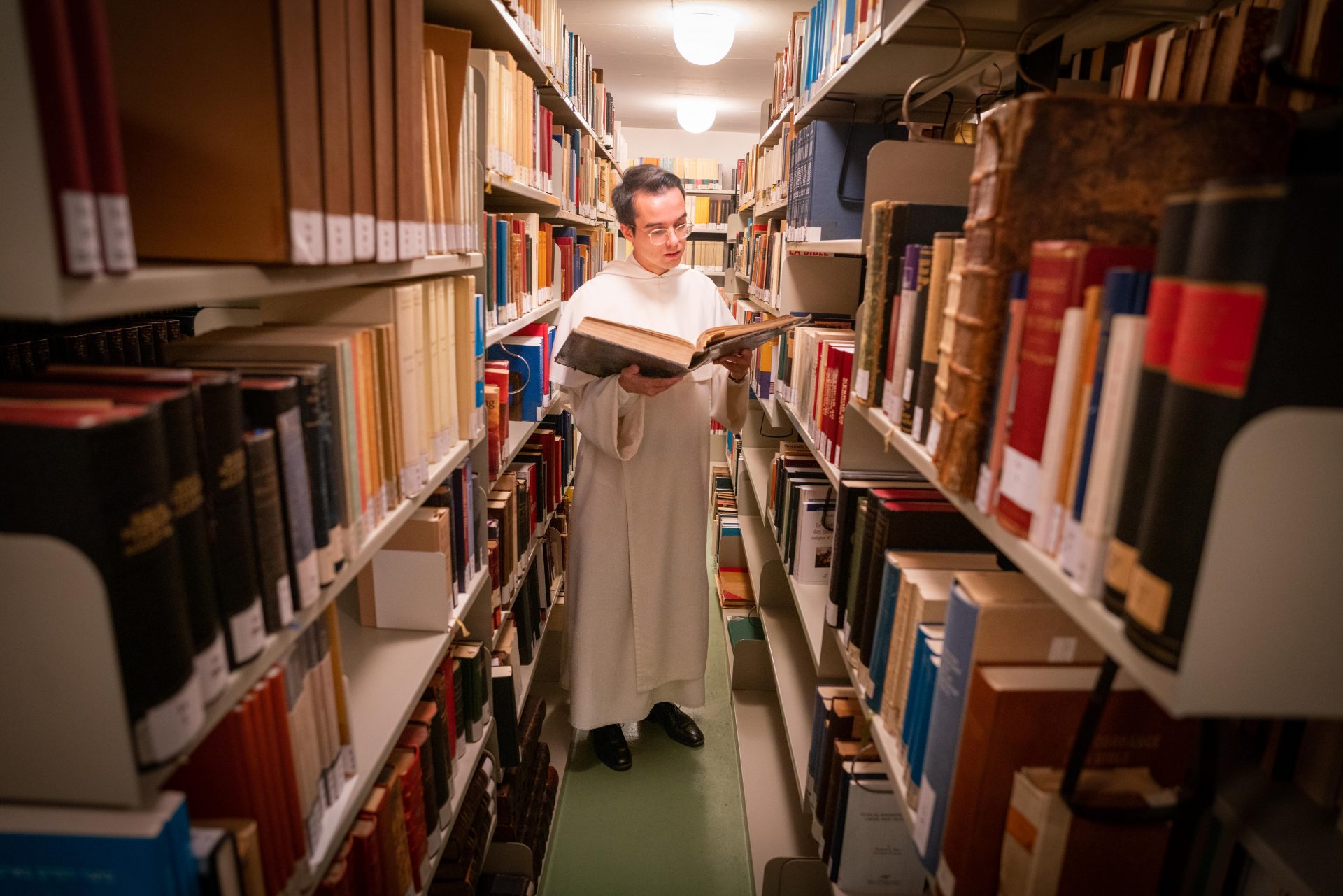

One important reason being that the Dominicans are a social order. ‘This is where we study,’ Ansinger says in the library, which is housed in a bunker under the monastery, a remnant of the Cold War. ‘But what is characteristic of our order is that we also go out into the world to preach.’

It is now ten past seven. In the monastery’s corridors, an electronic bell announces the start of vespers – the sung evening prayers. Nine brothers in white habits walk to the chapel: a large, bare space that Ansinger doesn’t particularly like. ‘The altar is far too austere – it looks like an IKEA table,’ he says. ‘But you have to make do with what you are given.’

Today, the former Radboud student is cantor. He launches with Psalm 135, marking the beat with his arm. ‘Rendez grâce au Seigneur: il est bon,’ sings Ansinger. ‘Éternel est son amour,’ reply the other eight brothers.

Monday, 7.45 p.m., refectory

Afterwards, Ansinger is not entirely satisfied. ‘The brothers with the best voices weren’t there today,’ he says. ‘In the morning it’s even worse: they’ve just got out of bed and sing four notes too low. I usually try to warm up my voice a bit in the shower.’

Ansinger’s great passion is Gregorian chanting. Three years ago, he and a fellow brother started the YouTube channel OPChant. In the videos, the brothers sing Gregorian chants according to the Dominican tradition, in special churches around the world. The channel has nearly 25,000 subscribers and some videos have been viewed more than 100,000 times.

The video channel has a crowdfunding page that has already raised more than €12,000. Ansinger re-invests this money in the project: to travel to beautiful churches in Switzerland, Italy, and Poland, or to buy a new camera. Thanks to a slider, the videos also have moving images; the brother does all the editing himself. ‘There are some useful tutorials on YouTube.’

In addition to YouTube, Ansinger is also active on Instagram and Twitter; together with a former fellow student, he creates the podcast De Herbergiers. ‘The Church needs to embrace modern issues,’ he says. ‘The Nijmegen theologian and Jesuit Petrus Canisius, who died in Fribourg, introduced the printing press here. His catechism travelled around the world as a result; it became one of the most translated Dutch books.’

The brother with whom the Dutchman founded OPChant left a few months ago, after seven years in the Order, Ansinger tells us over dinner at the refectory. On the wall is a large painting of 12 Dominicans, inspired by Da Vinci’s Last Supper. The buffet includes meat roast, a potato salad, a carrot salad, and pasta. There is a bottle of red wine on every table.

Ansinger does not comment on the reason why his fellow brother left, but it has certainly affected him. ‘I’m not angry at him, but it’s a bit like a divorce. The brother who left was asked to send a letter to Rome, and the reason for his departure has to be investigated. He was a good singer, and that’s hard to replace in a monastery.’

Ansinger himself has never doubted his vocation. ‘Of course, there have been difficult moments at the monastery. It’s the same as in a marriage, where you pledge to remain faithful to each other. A first crush can also be very overwhelming for a brother; it can haunt you for months. It’s important to talk about it with your fellow students and the student magister. In the end, you learn that strong friendships are also very valuable.’

All the brothers have finished eating, but Ansinger’s plate is still half full. ‘I am the slowest eater of the monastery,’ he says. ‘Please interrupt me if I’m talking too much.’ He laughs: ‘A priest friend told me that I suffer from organised hyperactivity, but I don’t feel that organised.’

Monday, 9 p.m., lower town

It is already almost dusk as we walk along the old city wall to the lower town of Fribourg. The town’s nickname is La petite Rome, says the brother. The study programme in theology at the secular University of Fribourg attracts not only lay people, but also Cistercians, Franciscans, Jesuits, and Dominicans, all of whom have their own monasteries in the city. ‘If you’re here on a Sunday, you can hear church bells ringing everywhere.’

‘Of course, there have been difficult moments at the monastery. It’s the same as in a marriage, where you pledge to remain faithful to each other’

Unlike some of the other brothers, Ansinger also wears his habit in town. ‘It’s our calling – it applies 24/7,’ he says. ‘It helps to introduce religion into the street scene. I’m often accosted or asked for prayers. You often end up in conversation, even in trains and airports.’

Peering down at low-Fribourg, Ansinger struggles to hold back a tear. ‘I’m going to miss this so much. It has been so special to live here for five years. I will definitely come back soon once I’m settled in the Netherlands.’

At Café du Gothard, a brasserie with wooden tables, panelled walls, and framed mountain views, Ansinger has arranged to meet members of the Catholic student association Teutonia for an informal drink – known locally as a Stammtisch.

Ansinger orders a white beer and toasts Alexander and Richard, a German and a Swiss student who have been drinking for a while. “Zum Wohl!” Throughout history, several Dominicans have been members of the student association, and Ansinger is keen to carry on the tradition. Alexander and Richard have occasionally attended mass at the monastery, they say. ‘When he spends the night at the pub, he sings better in the morning,’ Alexander says with a smile.

Tuesday, 7.30 a.m., Couvent Saint-Hyacinthe

Ansinger’s voice is struggling: he has to restart the morning hymn twice. ‘That never happens to me,’ he says afterwards. ‘But it has nothing to do with the Stammtisch, mind you. I was in bed by midnight.’

Tuesday, 9 a.m.

Ansinger takes us for a walk to Maigrauge, a convent for contemplative nuns founded in the thirteenth century. A sister lighting a candle in the chapel smiles briefly at the brother, who seems to enjoy the order’s centuries-old tradition.

From the valley, we climb to Notre Dame de Bourguillon, a chapel on a mountain popular with pilgrims. Ansinger gets down on his knees and prays silently.

Peter Canisius is said to have visited this place often. Ansinger has studied the life of the Nijmegen theologian. ‘Canisius preached a lot at the Fribourg cathedral; he revived the devotion of St Nicholas, and stood up for the poor. Like the Dominicans, Canisius felt that true preaching begins with good contemplation and study.’

The room where Canisius died in the Collège Saint- Michel, which is now a secondary school, is locked today. So the brother takes us instead to St Nicholas Cathedral, which houses Canisius’ remains. The relic includes two thigh bones and two shin bones of the saint and is shaped like an arm holding a pen. Nulla dies sine linea was Canisius’ motto: not a day passed when he did not write.

Tuesday, 11 a.m.

On the terrace of Café des Arcades, in the shadow of the cathedral, Ansinger orders a large Coke. He moves out of the sun and recounts one of the most difficult moments since his vocation: in February, one of his childhood friends died after a serious car accident. ‘When I rang his parents, all I could do was listen. Maarten had fallen into a coma right away and was transferred to Radboud university medical center. There, they soon found he was beyond saving. Via Skype, I held a prayer service in the room where he was lying.’

Three questions for Stefan

What did you want to become when you were little?

‘A priest and a musician. I was always happiest in church or in the concert hall – I loved anything to do with the human voice, the flute, and the violin.’

Where did you go this summer?

‘As Dominican brothers, travelling or at home, we are always together. Therefore, for me, the ideal holiday is in another contemplative monastery. I usually go to the Benedictines in Saint-Wandrille (Normandy) because of the heavenly Gregorian liturgy combined with excellent cooking!’

Who do you admire?

‘Dionysius the Carthusian (1402-1471), a learned ascetic southern Dutch Carthusian monk who prayed and worked tirelessly in the fields of philosophy, theology, and mysticism. His work breathes the various medieval theological schools.’

A week later, Ansinger conducted his first funeral as a deacon, in the church village of Oirlo. He had prepared the service down to the very last detail. ‘Maarten was capable of that higher form of friendship, the selfless kind. He would hang out in a bar until the last minute because he enjoyed being with his friends. I preached that in situations like this, something of Christian love returns. During the liturgy, I remained calm, but when I had to sprinkle the coffin with water and incense at the end of the mass, I broke down completely. It was very difficult.’

Even brothers sometimes face difficult moments. ‘If I’m facing a difficult period, I sometimes consult a psychologist. I’ve done so at times during my Dominican life, and I don’t feel ashamed about it. I think it’s good to hear a voice from the outside for once. This is also encouraged by the student magister.’

Tuesday, 1 p.m., refectory

How would they characterise their Dutch fellow brother? The brothers have to think about it after the afternoon mass. ‘Stefan is always very cheerful,’ says Brother Andreas Riis, a youthful-looking bearded 40-year-old from Denmark.

‘The only way to attract people is to try to stand for what inspires you’

‘He’s a bit postmodern,’ says Brother Emmanuel Durand, who has lectured Stefan as Professor of Theology at the University of Fribourg. ‘Despite his busy schedule, he often attended lectures, and was very diligent.’ Will they miss him when he moves back to the Netherlands in September? ‘That’s how it goes at this monastery,’ Riis says. ‘We’re very happy when new brothers arrive, but also always sad when they leave. But I’ll continue to follow him on YouTube.’

Tuesday, 1.30 p.m., monastery garden

After the summer, Ansinger will start working in the Netherlands, where he will contribute to the Erasmus University Rotterdam student apostolate. It is the last internship on his way to the priesthood, he says over coffee in the rose garden. ‘About three hundred, mostly international students, attend the English-language mass there every Sunday. I will assist with religious teaching, help people, maybe start a choir.’

Ansinger realises that people in the Netherlands are less religious than in this part of Switzerland. The Church is getting smaller, there are fewer believers. But he isn’t throwing in the towel. ‘The Church has had ups and downs for two thousand years. The only way to attract people is to try to stand for what inspires you. That way you show others that it’s possible to be blissfully happy in a church or in an order.’