European Diplomas in neurotechnology step by step becoming a reality

-

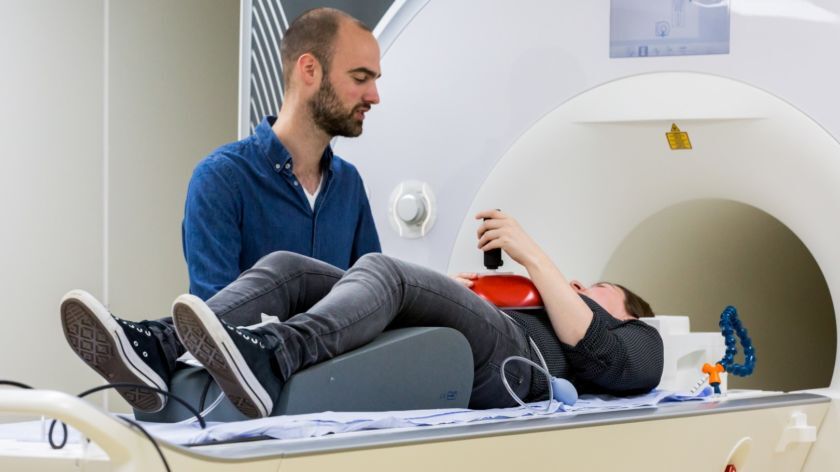

MRI scanner at the Donders Institute. Photo for illustration purposes (Vox)

MRI scanner at the Donders Institute. Photo for illustration purposes (Vox)

Handing out European Masters diplomas and setting up joint promotion trajectories. These are just a few goals of the European university NeurotechEU, of which the Radboud University is a driving force. At the same time, those taking the initiative closely follow the political decision making of the national and European politics, which can have an effect on the project.

If everything goes well, in September 2027, the first masters students will be studying at the European University NeurotechEU. Through physical exchange programs and online courses, students can take courses at one of the eight universities in the European alliance, which includes Radboud University. The ultimate goal is for them to receive a European degree in neurotechnology.

Online education is an important component of the system, says Professor Richard van Wezel, recently appointed coordinator of NeurotechEU, in a meeting room in the Huygens Building. ‘A lot of time has been spent jointly creating an online system where students can participate in digital education. But students or staff can also do an internship at a partner university for a while, for example, to learn a specific technique.’

‘Working out accreditation is one of the most important goals at this stage ’

How the course will be regulated for the quality of the education delivered is still an important point of discussion between the partnering universities, Van Wezel explains. ‘In this phase, working out accreditation is one of the most important goals’.

Emmanuel Macron

For over four years, Radboud University has been the driving force behind NeurotechEU. Eight universities from all corners of Europe (see box) are involved in the collaboration. In this second phase of the project, the alliance has a budget of up to 14 million euros.

The eight universities of NeurotechEU

Eight universities are working together in NeurotechEU. These are, in addition to Radboud University, the Universidad Miguel Hernández from Elche, Spain; the Karolinska Institutet in Sweden; the Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität from Bonn, Germany; the Bogaziçi Üniversitesi in Turkey; the Universitatea de Medicină și Farmacie din Cluj-Napoca from Romania; the Université de Lille in France; and, finally, the Háskólinn í Reykjavík in Iceland.

Emmanuel Macron was the one who came up with the initial idea of European Universities. In the meantime, there are nearly sixty similarly active European universities. Whoever were to take a look at the list of participating European Universities would see that virtually every Dutch university participates in an alliance. Neurotech EU distinguishes itself from the majority through clearly focussing on one area, namely brain and technology.

Brain Implants

Only a few European alliances have such a specific theme, Van Wezel elaborates. ‘Some of the universities that initially approached it broadly are now facing a problem: what will the focus be?’ he wonders. ‘We don’t have that problem.’

The focus on brain research makes it interesting for scientists to participate, according to Van Wezel. ‘And it just so happens that many Nijmegen scientists are working on this subject. With the Donders Institute and the Behavioural Science Institute (BSI), we are known for this both nationally and internationally.’

For example, Van Wezel himself works on the development of brain implants for blind people. ‘We conduct the research together with our partner university in Elche, Spain. The goal is for these individuals to receive an electrode in their head that provides them with a form of vision.’

“We are contemplating the question: what does it mean to work with the brain?”

‘But many other themes related to neurotechnology are also addressed at the European university, such as brain diseases like Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, or epilepsy. We also contemplate ethical issues and legal issues; what does it mean to work with the brain? Not only explicitly with implants, but also with medication or non-invasive techniques. Take artificial intelligence, for example: it is heavily based on how the brain works and will have even more impact on our society than it already does.’

International exchange of education is a goal of NeurotechEU, but according to the project leader, exchanging knowledge among staff, both scientific and support staff, is also important. This can occur at symposia and conferences on specific themes, such as certain brain diseases. ‘But we are also thinking about valorisation, so how do you disseminate this new knowledge to a broad audience?’

Political Decision-Making

As an EU project, NeurotechEU regularly deals with the complex outcomes of European and national political decision-making. According to Van Wezel, both the outcomes of national elections and those of the European Union as a whole can influence the progress of NeurotechEU. “Oxford University, one of the founding members of NeurotechEU, is no longer part of the alliance since Brexit. And because of a temporary ban on certain projects, Hungary no longer receives European funding, so the University of Debrecen is currently not a full partner but an ‘associate partner’ of the alliance.”

Translated by Nick Fidler