Heino Falcke writes book: ‘Without light, we cannot see the shadow of a black hole’

-

Heino Falcke. Foto: Erik van 't Hullenaar

Heino Falcke. Foto: Erik van 't Hullenaar

From the first look at the starry night sky to the image of a black hole. That is the journey described by religious astronomer Heino Falcke in the book “Light in the Darkness”, which is released today in Germany and will shortly be published in twelve more languages. “The presentation of that image was a definining moment in my life.”

After the presentation of the first image of a black hole (article in Dutch) at the European Commission in Brussels, various publishers approached Heino Falcke with the request to write a book. As he liked the idea, he contacted a book agent, he tells us on the phone while driving from his residence in a small city close to Cologne to Radboud University. ‘The call will disconnect in two minutes because I’ll be crossing the border.’

Four publishers were eventually bidding for the rights. Falcke chose Klett-Cotta, who also published Stephen Hawking’s last book. ‘They were willing to turn Licht im Dunkeln – English translation: Light in the Darkness – into a top title’, Falcke says. He wrote the book together with a journalist. ‘It was hard work. Lucky for me, I was already used to writing scientific articles in collaboration with multiple people.’

Small talk

This time, the astronomer intended to write a book for laymen instead of experts. He therefore took the lectures he has been giving in small rooms with fluorescent lighting for the past twenty years as a starting point. In these, he takes the audience along on a journey through the universe and explains the theory of relativity using a traffic situation involving a car and a police officer. ‘I use that in the book as well’, he adds. ‘In passing, I also tell some anecdotes from my own life and on other astronomers. As early as in the 18th century, astronomers travelled around the world to determine the size of the universe. We did the same in order to image the black hole.’

‘Humans have been watching the night sky for millennia’, Falcke says. ‘It has shaped, characterised and changed our culture and our view of the world. After reading the book, you should be able to make small talk about astronomy at a dinner party. I want to get readers to think about God, the world and the universe.’

What should you know about astronomy at a dinner party?

‘What is the origin of the seven days? Why were people in the olden days thrilled by astrology, and what error of reasoning was the base of that? Can we measure and predict everything, and is everything within the natural sciences set in stone?’

‘I am a firm believer in the natural laws. As physicists, we are proud of the predictability and reproducibility of experiments. However, we cannot predict the universe. Why is that? Because we have come to understand our own limitations. The book is an appreciation of science and of what we can do, but it is also an appreciation of what cannot be achieved.’

Light in the Darkness might as well be the title of a book on religion.

‘What makes black holes so unique is the fact that they are dark. But without light, we would not be able to see their shadow. Books written by scientists and astronomers are often very depressing: they constantly repeat how man is nothing. I try to describe what makes us unique: emotions such as belief, hope, love and passion are exceptional in this universe. It is our humanity that makes us special. I find searching very important. I want to encourage that in science, and for those who want in religion as well. Nothing is as unpleasant as a book that only provides answers.’

A significant part of the book revolves around the first image of a black hole.

‘The preamble is a long history of astronomy. As the Event Horizon Telescope team, we stand on the shoulders of the many generations of astronomical thinkers. I try to describe how my personal journey is linked with the grand journey. I bring the reader to my room in which I first thought that it would be possible to realise that image: an Amazing Grace moment, in which I could visualise my own thoughts as it were. The coming about of that image was a process that spanned many years and which I compare to being in love.’

‘At the end of the book, we pose the question what the image of the black hole and our knowledge of the Big Bang mean for astronomy and astrophysics. And is the query into the existence of God necessary at all? According to me, that question cannot be avoided.’

Radiation

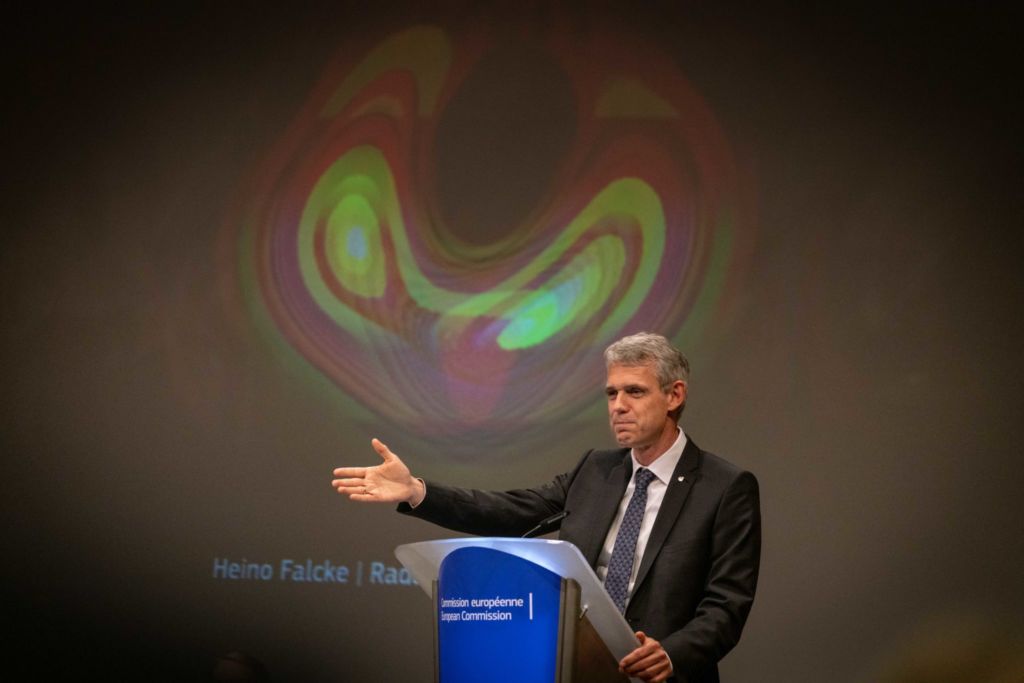

10 April 2019. People all over the world are watching the press conference at the European Commission in Brussels concerning the first image of a black hole. After an introduction by the European Commissioner for Research, Science and Innovation Carlos Moedas, Heino Falcke takes the stage. ‘This is the nucleus of the galaxy M87 and this is the first ever image of a black hole’, he says. On the screen behind him, the iconic black spot appears, draped in bright yellow radiation. Several seconds later, the image adorns the front pages of websites around the world, from Le Monde to the New York Times.

‘The Nobel Prize doesn’t keep me up at night’

‘It was a defining moment in my life’, Falcke says today. ‘The road to get there was an incredible ride. After the presentation, my agenda got very busy: in 2019, I gave a total of 120 interviews and lectures. Then the coronavirus crisis hit. It temporarily stopped everything, which gave me the time to finish this book. Sometimes, you need to be forced to take some time off.’

Since the presentation, journalists have called you a candidate for the Nobel Prize. How do you deal with that?

‘It’s horrible. I am somewhat afraid that in the next twenty years, I will always be mentioned as the one who did not get the Nobel Prize. You can ask my colleagues: it isn’t something that keeps me up at night.’

Two weeks after this interview, the German astrophysicist Reinhard Genzel and the American astronomer Andrea Ghez were awarded the Nobel Prize for their discovery of a black hole at the centre of the Milky Way. ‘I am happy for them and congratulated them’, Heino Falcke writes in an email. ‘They have really earned it. Their work was part of my inspiration; I wrote a chapter on them. They managed to measure the mass of a black hole very precisely; we are currently observing the event horizon.’

Have you since been recognised in the supermarket or in the streets?

‘No. I am on television occasionally, but people hardly ever address me on that subject. Many people have seen the image of the black hole but do not know which scientists were involved in the realisation. It only happens at lectures that people ask for my autograph.’

Has there been an increase in young people starting astronomy studies since the image of the black hole?

‘When we established the Physics and Astronomy programme in Nijmegen, we started with 20 students. Currently, we have 140. Last year, I asked the students during a lecture whether that image had influenced their decision to study physics. They said it did make a difference. It moved me that the image gave some students that final push in this direction.’

Several PhD candidates who contributed to the coming about of the image of the black hole have since defended their dissertations and moved abroad. Does that hurt?

‘Such is life. It is my duty to make sure that they can enter the world as proper scientists, similar to what I did with my children in a different context. We had a terrific team and went through a lot together. Since it was so demanding, we did not always make sufficient time for each other. By the time it was possible, the coronavirus arrived. I might seem very sober-minded, but I sometimes tear up when thinking about it.’

‘Our PhD candidates attained a very high level’

‘No other group did as much with PhD candidates as ours. At a young age and without dissertation, they attained the same level as scientists at Harvard or MIT and they are now taking on great positions and jobs. That might be the most important result that the black hole has yielded for me.’

Is the most important moment of your career behind you?

‘In football, the most important match is always the next one; the same applies to a scientific career. I am not somebody who looks back too much. I did do that for the book, since I felt an important responsibility as figurehead to do something with it. I still have many plans and ideas, but the time to realise them is becoming shorter and the money is dwindling. I am now running on my scientific financial fumes. Getting new funding and drawing in and training new people is extremely hard work. Scientifically speaking, I am starting over almost entirely, although I do have a network and talented colleagues, of course.’

Were you hoping that by this stage in your career, it would be easier to be awarded funding?

‘I should not really be saying anything on this subject, lest I raise another Twitter storm. However, it is definitely not easier to apply for funding than it used to be. I am somewhat older, but even if I work for hours at night, I do not have sufficient time to write all the proposals that I might want to do.’

What are the major challenges in astronomy for the years to come?

‘How much time do have you left? (laughs) What resulted from the image of the black hole is an intensification toward the research into gravity at the intersection of astronomy and physics. We must learn to understand space-time physics. I hope that exciting discussions will arise regarding the combination of quantum physics and the theory of relativity. There are still some fundamental aspects to be discovered there. Other subjects into which much research can still be done are the origin of the Big Bang, dark energy and dark matter, and the question whether there is life elsewhere in the universe.’

Twelve languages

The first edition of Licht im Dunkeln will be circulated in Germany at 20,000 copies. The translation rights have already been sold to twelve countries, including for English (worldwide), French, Chinese, Spanish and Finnish. The Dutch version, entitled Licht in de Duisternis, will be available in book shops from 30 October.