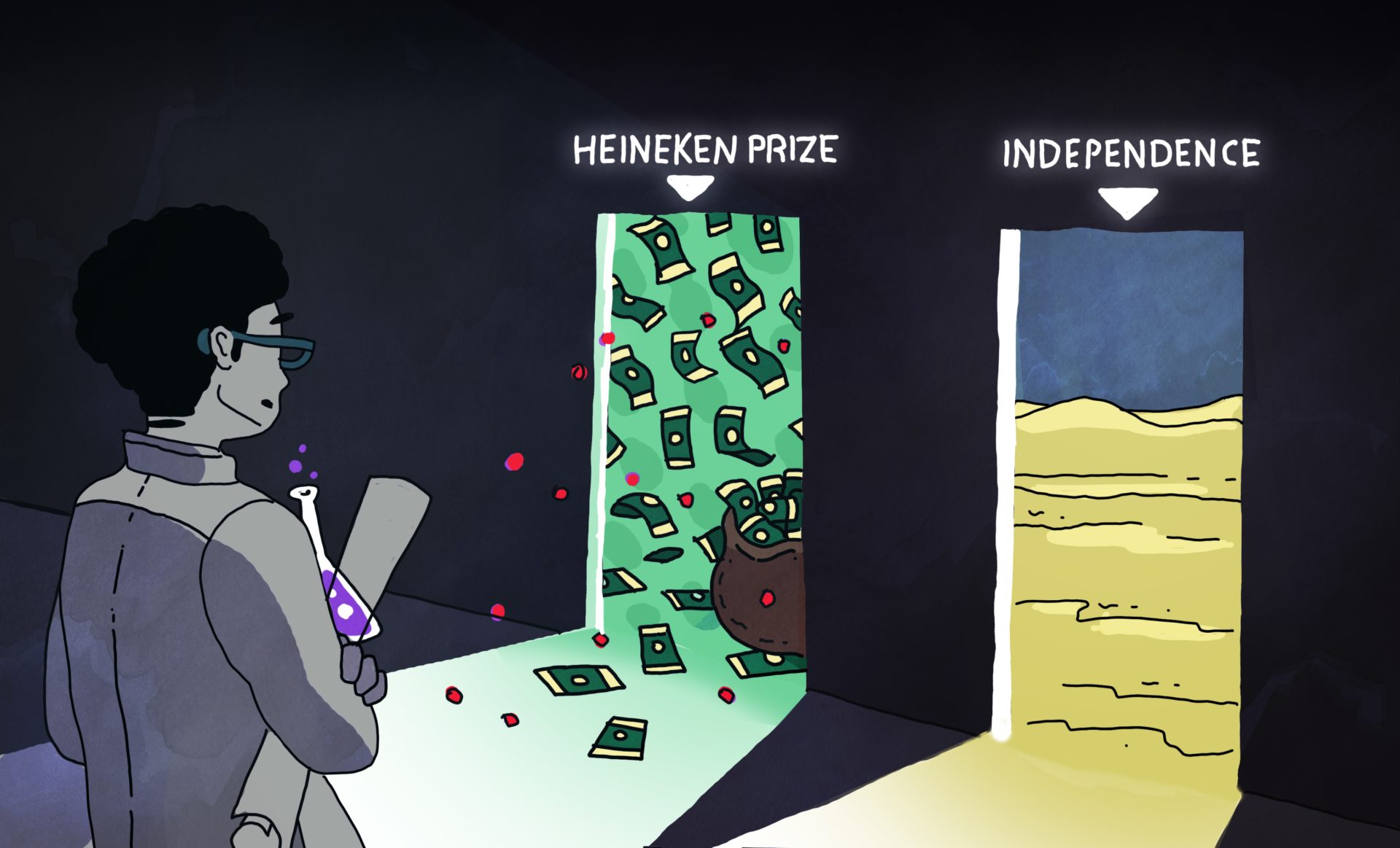

How Heineken and Shell create dilemmas for researchers with sponsored prizes

-

Illustratie: Ivana Smudja

Illustratie: Ivana Smudja

On Thursday, the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW) is awarding the Heineken Prizes. An important scientific award or pure advertising for the brewery? Sponsored awards are omnipresent in science. But are they also compromising academy independence?

‘The most prestigious Dutch prizes for art and science.’ That is how the Alfred Heineken Foundation describes the prizes they award every second year; the 2022 prizes will be awarded this Thursday. The Heineken Prizes – six for renowned researchers and four Young Scientist Awards for upcoming talent – are indeed prestigious. Winners of the ‘first prizes’ are each granted a sum of €200,000, and have above-average chances of later winning a Nobel Prize. It is therefore no surprise that the media refer to them as the ‘Dutch Nobel Prizes’.

And yet, there is a bitter aftertaste to the Heineken Prizes, as Professor of Mathematics Klaas Landsman recently argued in NRC. This has to do with the fact that the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW) academic association is responsible both for the judging and for awarding the prizes. ‘In this way, the KNAW is acting as advertising column for a company that earns its money selling poison,’ writes the professor (a KNAW member himself), referring to the adverse health effects of alcohol. ‘The KNAW is contributing to these advertisements by creating a positive association with the Heineken name.’

Undesirable influence

Landsman’s argument is part of a debate that is as old as science itself: aren’t universities too much at the service of the business sector? Often, these concerns arise in response to the financing of research, for example into medicines.

According to a 2020 report by the Rathenau Institute, one in eight researchers has at times experienced undesirable influence from companies. The question is to what extent this also plays a role in the commercial financing of prizes. For example, could a researcher who studied the adverse effects of alcohol on the brain ever win a Heineken Prize?

Of course they could, says Roshan Cools. As Professor of Cognitive Neuropsychiatry, she chaired this year’s KNAW jury responsible for awarding the Heineken Prize for cognitive sciences, which went to the Brazilian-British neuroscientist Kia Nobre (Oxford).

‘Researchers mostly associate the Heineken Prizes with prestige, not with beer.’

The foundation financing the Heineken Prizes is legally independent of the Heineken brand, emphasises Cools in her office at the Donders Centre for Cognitive Neuroimaging. Formally, this foundation belongs to the Heineken family, not to the company. ‘Researchers mostly associate the Heineken Prizes with prestige, not with beer. The Heineken company therefore has no influence whatsoever on the Prizes’ content.’

In fact, neither does the foundation, she adds. The KNAW supervises the entire award process, from A to Z. The foundation asks a number of organisations, including the Young Academy and the Network of Women Professors to put forward candidates. The jury, whom Cools, in her position as chair, selected personally, then creates a shortlist and asks external referents for an appraisal, after which they select a final winner. This is not very different from the procedure for important publicly funded prizes such as the Dutch Research Council (NWO, ed.) Spinoza Award.

It is clearly no coincidence that the prize and the beer brand bear the same name, says Klaas Landsman. Sponsoring prizes is very good PR; after all, the general public does associate the name Heineken with beer. ‘I’m sure that the jury really is independent,’ he says. ‘My point is that the KNAW likes to advertise itself as the “voice and conscience” of Dutch science. By doing so, it places itself on a rather high moral pedestal. As a consequence, it cannot afford to become associated with a company that creates products that are harmful to health, or with events like the Formula 1 championship.’

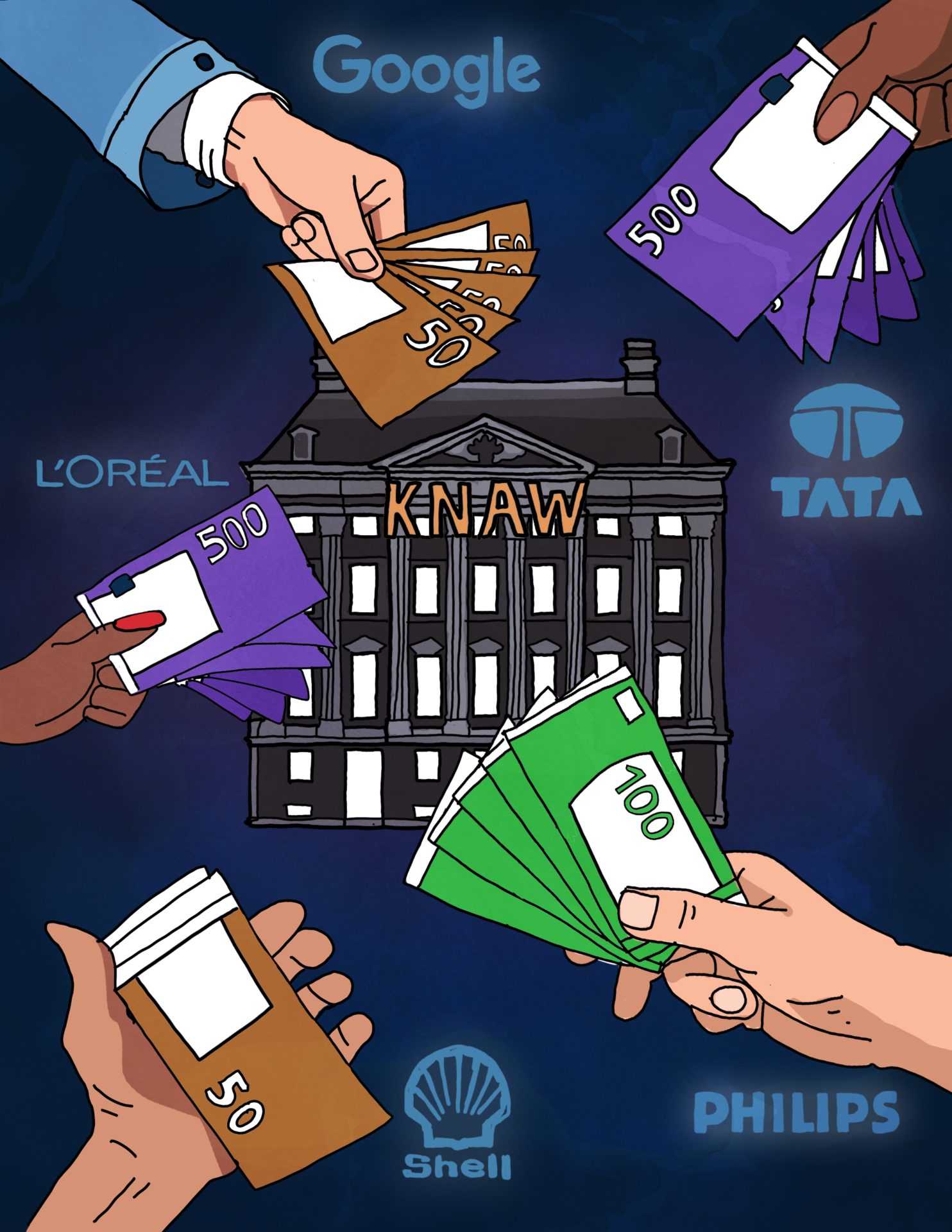

Tata Steel

The KNAW is not the only academic association with commercially tinted prizes. The Royal Holland Society of Sciences and Humanities (Koninklijke Hollandse Maatschappij der Wetenschappen) (KHMW, the ‘older sister’ of the KNAW, founded in 1752) also has many of its student prizes – which range from a few hundred to thousands of euros – financed by multinationals. These include the Shell Graduation Award for Physics, the Schiphol Incentive Award for Aerospace Engineering, and the Tata Steel Graduation Award for Mechanical Engineering and Materials Science (see box). These are not really companies that have the best reputation at the moment.

Sponsored awards

Both companies and various non-profit organisations are attaching their name to scientific awards. Here are a few notable examples:

• Nobel Prizes (8 million Swedish crowns, approximately €800,000)

• Heineken Prizes (€200,000)

• L’Oréal-UNESCO Award for Women in Science ($100,000)

• Coca-Cola Stipend for Sports Medicine (until the early 2000s)

• Niels Stensen Fellowship for researchers (until 2015 only Catholic researchers) (€50,000)

• Pfizer Graduation Award for Life Sciences (€1,000-€3,000)

• Tata Steel Graduation Award for Mechanical Engineering and Materials Science (€5,000)

• ASML Graduation Award for Mathematics (€5,000)

• Shell Graduation Award for Physics (€1,000-€3,000)

• Shell Incentive Award for Chemistry (€500)

At international level, it is also very common for respectable organisations to become associated with a private sponsor. The best-known example are the Nobel Prizes: financed by the Nobel Foundation (based on the legacy of dynamite inventor Alfred Nobel), but formally awarded by Swedish and Norwegian academic institutions such as the Karolinska Institute. The United Nations use a similar construction with the L’Oréal-UNESCO Award ($100,000), a renowned prize for women in science.

In principle, there is nothing wrong with this construction, says Professor Cools. ‘I think the academic world is actually very happy to have private money invested in science. I personally see a lot of value in collaboration between universities and the business sector. It brings companies closer to society, and allows them to stimulate demand-driven research. Ultimately, researchers also often want to solve societal problems, for example around mental well-being.’ And don’t forget, she says, that many companies are also involved in doing research. This makes it logical for them to look for partners to work with.

It is important to make good agreements when you get involved with companies, emphasises Cools, for example when deciding who has a say about what will appear in scientific publications. ‘But this is not an issue with sponsored prizes, since they are awarded for research that’s already been completed.’

No downplaying concerns

Researcher Luca Consoli, from the Institute for Science in Society (FNWI), concurs. ‘The debate around the influence of companies on science in general – separately from the whole Heineken discussion – is very important, but it often becomes rather black-and-white,’ says the Associate Professor of Science and Society. ‘I think you have to look for the nuance. The business sector has always played an important role in the relationship between science and society. Look for example at how Philips and universities joined forces to create all kinds of valuable products.’

This certainly doesn’t mean that all concerns should be downplayed, he emphasises. ‘As a researcher, you should always remain alert in your dealings with companies. What are their interests? What do you want? You have to make clear agreements. This is why it is also important that the institution where you work sketches clear conditions and offers support in the negotiations. In Nijmegen, this is quite well organised.’

‘Heineken is not a forbidden company; people also enjoy drinking alcohol’

‘Complete academic independence is an illusion. By aspiring to a very high level of academic purism, you place yourself outside of society,’ says René ten Bos, Professor of Philosophy of the Management Sciences. Commerce has always been closely linked to academia, and sponsored prizes are just one exponent of this. Abolishing them will not change much to the situation, he argues. ‘And Heineken is not a forbidden company; people also enjoy drinking alcohol. This is not the tobacco or weapons industry we’re talking about. As far as I’m concerned, these considerations should be left to the individual conscience of researchers themselves. There’s no getting around the fact that much of what we do these days is morally ambivalent.’

Sexual harassment

And yet, the idea that manipulation is always lurking is not purely hypothetical. Laureates may, consciously or unconsciously, adopt a milder perspective towards their sponsor. For philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, the fear of losing his independence was enough reason to turn down the Nobel Prize in 1964. And when Heineken Art Prize winner Erik van Lieshout spoke negatively about the brewery in 2018 – after it had come to light that Heineken workers in Africa had been guilty of sexual harassment – he says that he was asked by the Heineken PR Office to retract his comments. He considered returning the prize money, but decided to spend part of it on creating a documentary about his struggle with the prize, called Beer.

Within the academic community, too, people worry about the influence of multinationals. For example microbiologist Marjan Smeulders, who is active within the Scientists4Future climate action group, and who has in the past called on the ABP pension fund to stop investing in fossil fuel companies like Shell. ‘Fossil sponsoring at universities will soon be put on the agenda of Scientists4Future,’ she informs us by email.

‘Personally, I was shocked to hear that the University of Twente Green Team is working on a hydrogen car for the Shell EcoMarathon competition.’ In this ‘sustainability competition’, teams have to drive as far as they can on one litre of fuel. A car running on hydrogen also perfectly fits the business model of fossil fuel companies, argues Smeulders: making fuel for combustion engines. ‘This allows them to keep doing what they’re doing, and that while electric cars are far more energy-efficient.’

‘Prize winners are proud’

So far, the concerns of Landsman and others have not led to much change. The KNAW is not planning to review its current partnership with Heineken, says a spokesperson in a written response: ‘The Heineken Prizes are not paid by the Heineken company, but by the family, from the A.H. Heineken Foundation funds.’ Nor is the KNAW itself receiving any money. ‘The prize winners and their teams are proud of their prizes and use the money to further scientific research.’

The Board of the Science Faculty, which nominates students for the awards of KNAW sister KHMW, has not yet put commercial sponsoring on the agenda, says Dean Sijbrand de Jong in response to our question. As a ‘citizen and KHMW member’, he is however thinking about it, he emails us, partly in the wake of Klaas Landsman’s opinion piece. ‘But I don’t yet have a clear enough stance on it to express my opinion.’

Nijmegen laureates are not worried

Neuroscientist Floris de Lange (Heineken Young Scientist Award, 2012)

‘I don’t have any problems with the Heineken name. Heineken is not an objectionable company; the idea that the KNAW is becoming associated with ‘poison’ sounds like an exaggeration to me. And as far as I’m concerned, there is no question of compromising scientific integrity, because the KNAW is doing the judging. Compare it with the Nobel Prize, which is also financed with money that Alfred Nobel earned by developing dynamite. No one finds that problematic.’

Linguist Mark Dingemanse (Heineken Young Scientist Award, 2018)

‘I found it an honour to win the Young Scientist Award in Humanities. What is crucial for me is that the KNAW is responsible for the entire procedure, from nomination to selection and conferment. I wouldn’t be so enthusiastic about a prize awarded by a company, but that’s not what this is. As far as I’m concerned, it would be better if prizes were not named after people at all. Once a name becomes established, as is the case with the Heineken Prizes, it’s hard to change it – although not impossible.’

mRNA-expert Katalin Karikó (University of Pennsylvania; recipient of Radboud University Honorary Doctorate and winner of this year’s L’Oréal-UNESCO Award for Women in Science)

‘I think that the good thing about these kind of prizes is that they put researchers in the spotlight. This is very much needed, because if you ask an average person on the street to name three modern-day top scientists, they wouldn’t be able to tell you. L’Oréal is spending their money in a useful way; they are awarding prizes for women scientists on every single continent. Plus, as a university, you cannot manage on public funding alone, and sponsors are sorely needed for good science. Such constructions are far more common in the US than in Europe.’

Philosopher Fleur Jongepier, this year’s winner of a Heineken Young Talent Award, was not available for comment.

This article was translated by Radboud in’to Languages