In Nijmegen too, sexual harassment is the order of the day

-

Illustratie: Prachatai

Illustratie: Prachatai

In the Netherlands, one in ten female students is a victim of rape during her student days. This was the conclusion of last year’s survey commissioned by Amnesty International. Vox conducted its own survey into the experiences of Radboud students. The results aren’t reassuring. Sexual harassment, unwanted touching, catcalling, sexist jokes, and rape are a problem in Nijmegen too.

1. Most perpetrators are men

In the Vox survey 28 students (11%) report having experienced unwanted penetration and 13 students (5%) report experiencing unwanted oral sex. More than half of these cases involved ‘proceeding without checking’, in other words: the person’s bed partner not asking for their consent before proceeding. In other cases, the other person insisted or pestered the victim for sex. In 20 cases, the perpetrator of sexually transgressive behaviour misused the fact that the victim was under the influence of alcohol or drugs. A large majority of the perpetrators was male (27 men versus 4 women).

Justification

Between 29 June and 5 September 2022, 254 students completed the Vox questionnaire. Of the respondents, 35% were Master’s students, 2% Pre-Master’s students, and 63% Bachelor’s students. 12 % were international students. 30% of the respondents were male, 67% female, 2% did not identify with either gender, and 1% preferred not to say.

What constitutes sexually transgressive behaviour? The Rutgers Centre on Sexuality speaks of a positive sexual interaction if there is mutual consent, voluntariness, and equality. If one or more of these conditions are not met, this is a sexual transgression.

Vox is aware of the methodological challenges inherent to an open survey. For example, the number of respondents was too small to make well-supported statements about all Radboud University students. Nevertheless, the results do send out important signals concerning the extent of the problem.

The survey was designed by the Rotterdam university weekly publication Erasmus Magazine, in collaboration with researchers, diversity officers, and a confidential advisor from Erasmus University Rotterdam.

Nearly half of the victims reported experiencing problems afterwards and 4 out of 5 students who had experienced penetration or oral sex without consent reported experiencing psychological problems. In the case of men, this also affected their study results, while women mostly experienced sexual problems. Many students only later became aware of the severity of what had happened. In some cases, this was due to being unwilling or unable to talk about it at first, due to shame or trauma.

According to Marijke Naezer, independent researcher on gender, diversity, and sexuality, the Vox survey results are in line with previous research, such as that of Amnesty International, which shows that 11% of female students experience rape during their time as a student. ‘We have a huge problem with consent,’ she says. ‘I’m afraid that some of the perpetrators aren’t even aware they are crossing a boundary.’

The fact that most perpetrators are men is a well-known fact, says Naezer, and this is related to gender norms and ideas about masculinity. ‘Man the hunter. If a woman says “no”, you should insist. That kind of thing.’ The results of the survey are a consequence of this kind of culture, according to Naezer.

At the same time, she wants to add a caveat: we are probably missing a lot of the male victims. ‘When a man is asked whether he has been the victim of transgressive behaviour, he’s more likely to deny it. After all, the stereotype of a man is that he should always be interested in sex, and if not, he has to defend himself. Then if something unpleasant happens to him, we’re quick to tell him not to make a fuss.’

2. Victim blaiming is part of our culture

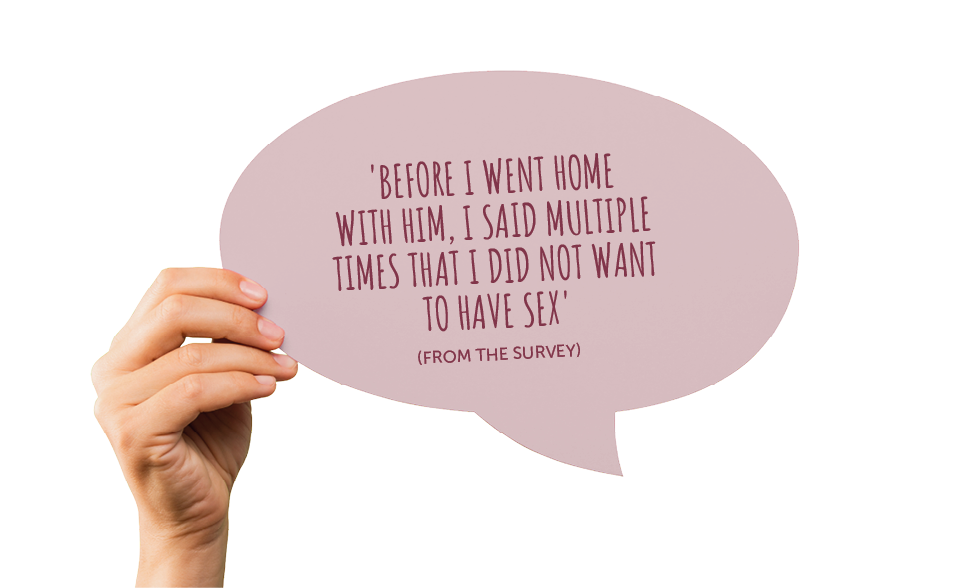

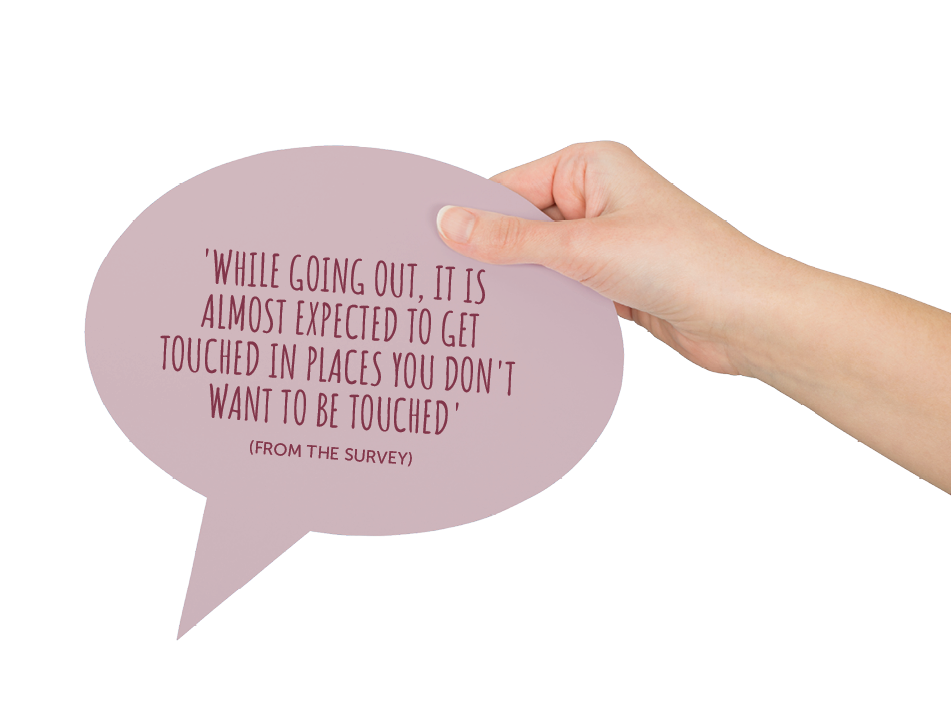

Just over half of the survey respondents report experiencing unwanted touching. Among women, this percentage is 61%. Very often, these incidents occur while out partying. ‘Nearly every time I go out, I’m assaulted,’ says a medical student. ‘It might sound strange, but I don’t see it as something out of the ordinary anymore,’ reports a student from the Nijmegen School of Management.

According to Naezer, this is something cafés could be a lot more attentive to. ‘Bar personnel and bouncers should intervene if they see or hear something. This is most definitely not always the case now.’ Another smart measure: don’t hide the toilets in a dark cellar, but make sure they are located in a well-lit space, preferably with someone to monitor things.

Another phenomenon that women now have to take into account when going out at night is street harassment, also known as catcalling. These can be sexually coloured remarks, but also sissing or staring. A total of 118 respondents have been exposed to it at some time or another. The consequence is that people no longer feel safe on the street. ‘I also find trains quite scary,’ reports a female student from the Faculty of Philosophy, Theology and Religious Studies.

‘Victims who do speak out are by no means always taken seriously’

Students seem to already anticipate that they might be the victim of harassment or even assault. This is a well-known phenomenon, confirms Naezer. ‘Especially women and other gender minorities anticipate incidents like these in various ways. They walk with a bunch of keys in their hands, which they can use to hit their assailant. Or they pretend to be on the phone. They pull their hood over their long hair, don’t accept drinks from strangers, drink less alcohol.’ Women are caught in a balancing act: the norm is to dress in a sexy way, but if you put on a short skirt, it can be used as an excuse for unwanted touching.

‘So even if no actual violence takes place, sexually transgressive behaviour impacts the lives of women and other gender minorities,’ says Naezer. ‘Because you can’t be who you want to be. You always have to take “what if” into account.’

The painful irony of it, according to Naezer, is that when something does go wrong, it is in our culture to implicitly blame the victim. ‘We ask the victim: “What were you wearing? How much did you drink? What should you have done?” Plus, victims who do speak out are by no means always taken seriously. ‘It’s hard to prove that something like this happened. It’s often one person’s word against another’s, which doesn’t get you any further.’

3. The danger of alcohol

We should talk about… perpetrators. ‘How we talk about sexual violence has a strong effect on how we think about it,’ says Naezer. ‘Perspectives are very important in this context. If we only talk about victims, the perpetrators remain invisible, and we automatically place some of the blame on the victims.’

This is why the Vox survey also included questions about whether the respondents ever felt that they had crossed another person’s boundary. 62 students answered “yes”. And these weren’t all men. 25 women also admitted to transgressive behaviour. ‘Sometimes I’m drunk and I’m afraid that I may not have noticed that the other person didn’t really want to proceed,’ says a female medical student.

More students doubt the integrity of their actions when they are under the influence of alcohol. One student from the science faculty reports: ‘I was very drunk myself and I didn’t remember what happened; it was only later that I heard that I was a bit pushy (sic).’

‘We have to talk to students about sex’

Having too much to drink and not explicitly asking for consent seem to be the main reasons for students to feel that they may have crossed someone’s boundaries. 23 respondents reported proceeding with sex without checking that the other person was OK with it.

According to Naezer, the advantage is that people are daring to be more vulnerable, look in the mirror, and admit that they have gone too far. ‘It’s not that you immediately have to be ostracised when you admit to something like this. I, for one thing, think it’s very brave. And it’s the only way to talk about it to each other, and bring about change.’

4. The responsibility of the university

Although most incidents around sexually transgressive behaviour do not take place on campus – they are far more likely to occur at home or on a night out – many students believe that the University does have a responsibility when it comes to social safety. A majority (59%) of the 254 respondents expect the University to raise awareness around healthy and desirable behaviour when it comes to sex. 39% expect the University to offer consent training programmes (33% is neutral, 27% doesn’t expect it).

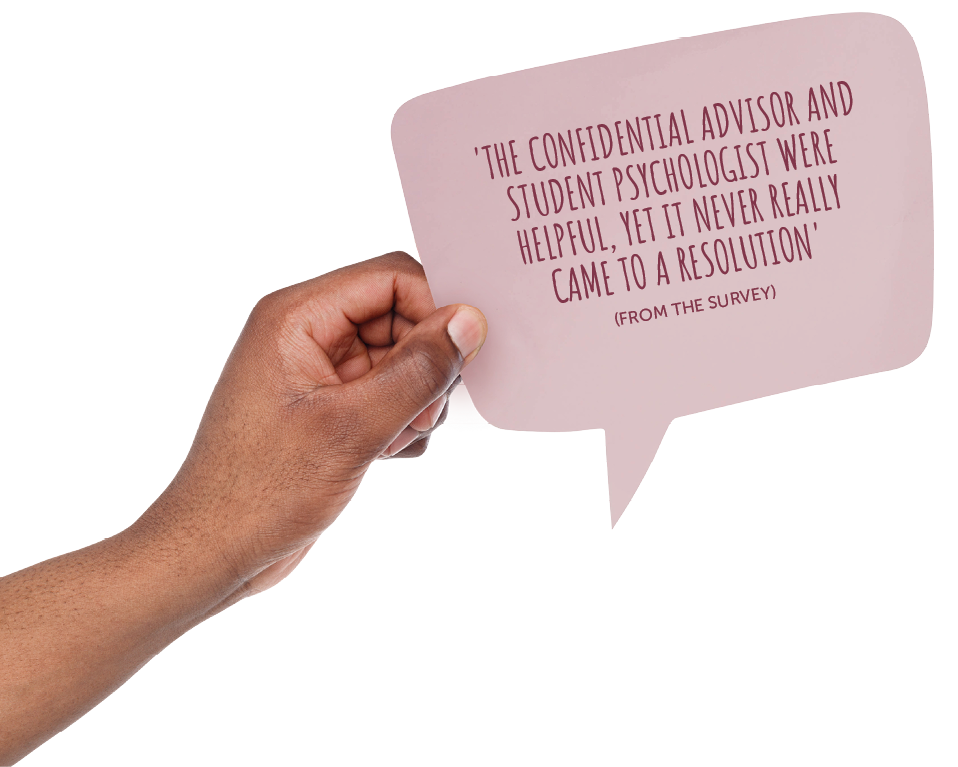

Students who have been the victim of transgressive behaviour can talk about it to a University confidential advisor. It doesn’t matter whether the incident takes place on campus or not. The confidential advisor offers a listening ear and advises on potential follow-up steps. And yet, few students make use of this service. ‘My situation doesn’t have much to do with the University, since it didn’t take place on campus,’ a student tells Vox. ‘I feel that if I wanted to report it, I’d have to do it by filing a police report,’ says another student.

Marijke Naezer understands this, but the universities still have an important role to play in this context. ‘First of all, there has to be good support for the victims who do want to report an incident. But the University should also offer training and information. We’re all pretending that young people’s sexual education stops once they leave secondary school, which is clearly not the case. We have to talk to students about sex.’

A voluntary workshop here and there isn’t enough. ‘Make consent training programmes part of the curriculum. Make it compulsory. Otherwise, it will only attract the people who already behave.’ Another important aspect according to Naezer is what is known as active bystander training. ‘Many people have at times witnessed transgressive behaviour, but failed to recognise it as such. Or they didn’t feel responsible, or didn’t know how to respond. This is something you have to help people with.’

According to Naezer, it doesn’t make much sense to talk about the extent of the University’s responsibility in this respect in legal terms. ‘I’d much rather see universities show proof of vision in this respect. You want students to be safe when they’re studying, don’t you? That’s not going to happen if they experience sexual trauma. And universities are training future professionals; surely, we want these to be people who take responsibility for their own actions?’

Finally, universities should respond adequately when a case of transgressive behaviour comes to light. ‘I’m not impressed by the thoroughness of universities in cases like these. If victims see that people in high positions are enjoying undue protection, they’ll think twice before reporting transgressive behaviour.’