Limits to growth (1): the growing pains of Radboud University

-

Illustratie: Ivana Smudja

Illustratie: Ivana Smudja

Every year Radboud University becomes a little bigger. What do fuller lecture halls mean for education, student life and the city of Nijmegen? In the series Limits to growth, Vox dives into the university's growing pains. Today part 1: in ten years' time, the number of students has grown by more than a third.

‘I hope there will be popcorn’, first-year students joked during the bus trip from the university campus to CineMec near the Lentse Plas, in 2016. While the mega-cinema normally shows blockbusters, five years ago the bright red building served as a lecture hall for first-year psychology students.

Limits to growth

In the coming weeks, Vox will highlight the steady growth of the university. This is the first article in the series.

1. The growing pains of the university

2. Active student life under pressure

3. Fighting for office space

4. The sports centre is bursting at the seams

5. The explosion of psychology in 2016

6. How accessible is the campus anymore?

7. Lecture halls full of unhappy students

8. Student recruitment without growth ambition

The study programme was so overwhelmed by the sudden influx of more than six hundred students – more than double the usual amount – that even the largest auditorium on campus did not have enough room to host them all. As an emergency measure, they followed their first lectures from the cinema seats.

If you want to know how abruptly growing student numbers can cause headaches at the university, you should take a look at the turbulent growth at psychology in 2016. Much more gradually, but very steadily, Radboud University as a whole also grew over the past decade. Which study programmes grew the fastest? And how does the university see this growth and its consequences, both inside and outside the campus?

A little bigger every year

To start with the hard facts: figures from Radboud University show that the university has attracted more students each year over the past decade. In 2012, there were 17.846 students enrolled, while in the current academic year there are 24.159 – a growth of 35 percent. By comparison, the population of the city of Nijmegen grew by 7 percent in the same period, to 177 thousand.

Especially the Faculties of Management, Social Sciences, and Natural Sciences (FNWI) worked like magnets attracting new students. But it was the small Faculty of Philosophy, Theology and Religious Studies that grew the fastest, in relative numbers: from over 500 students in 2012 to double that in 2021.

At the programme level, it is especially the Bachelor of Business Administration that is on the rise. Ten years ago, this study programme housed 855 students, now there are 1510. In percentages, Computing Science has gained the most in popularity: in ten years’ time, this programme has more than quadrupled in size (from 121 to 504 students). In absolute terms, the Bachelor of Psychology is still the largest study programme at Radboud University, with 1723 in total, followed by Law and Business Administration, with over 1500 students.

Radboud University’s growth resembles the national trend. All thirteen Dutch universities have attracted more students over the last ten years. In total, the number of enrolled students increased by 40 percent since 2012. Leiden University, for example, grew by 63 percent; in that light, Radboud University’s growth is only modest.

In contrast, universities of applied sciences (hbo’s) attracted fewer first-year students. In 2021, 8.6 percent fewer than in the previous year. The contrast with universities is striking and can partly be explained by the fact that students are increasingly encouraged to pursue the highest possible level of education.

Internationalisation

Another, perhaps even more important reason for the growth of Dutch universities is internationalisation. Because Dutch universities have a good reputation and many courses are offered in English, foreign students are increasingly attracted to the Netherlands. This academic year, some 29 percent of the new bachelor’s students at Dutch universities come from abroad, compared to 24 percent in 2020.

Radboud University is keeping up with this trend. Some programmes have switched entirely to English, such as biology and computer science; others opt for a Dutch and English track, such as business administration and psychology. In the 2019-2020 academic year, 23 of the 37 bachelor’s programmes were still entirely in Dutch.

Partly due to this growing offer, the number of foreign students at Radboud University has almost doubled in the past decade. In 2012 there were 1480 international students enrolled, according to the university’s own figures, now there are 2718, with the vast majority coming from Europe. However, as the number of Dutch students has also increased significantly, the international population has not grown much in proportion: from 8.3 percent in 2012 to 11.2 percent now.

Nevertheless, universities are concerned. They are asking the government for more instruments to control the (international) inflow. ‘This continued growth puts even more pressure on our staff and the quality of our education,’ said Pieter Duisenberg, chair of Universities of the Netherlands (UNL), in a press release in November when the inflow of the current academic year became clear. The UNL points out that the state contribution per student has been lagging behind the growth for years.

Radboud University has been saying for years that it is no ‘growth ambition’

With lecture halls becoming ever more crowded, the ratio of lecturers to students has also grown further apart. In 2012, Radboud University had an average of over 17 students per lecturer, according to UNL figures. In 2018, that ratio was 21.7 to 1, and in 2020 it was still 20.8. The more uneven the ratio, the greater the workload: lecturers have to supervise more students.

Emergency housing

The Executive Board in Nijmegen is also concerned about the ever-increasing student intake. Rector Han van Krieken emphasises that the increasing numbers – in combination with the financing from The Hague that is lagging behind – endanger the quality of education. ‘It was not just for fun that chairman Daniël Wigboldus was there when Erasmus was carried to the Waal’, he says, referring to a protest against the underfunding of higher education in April last year. A statue of Erasmus was symbolically put in the Waal with his head almost under water, to emphasise how urgent the need for better funding is.

Small-scale, high-quality education. That is the type of education that Radboud University likes to offer. Van Krieken acknowledges that this ambition is at odds with the lack of lecturers. Money is not the most limiting factor. The university is actively recruiting more staff. The latest marketing campaign – ‘You have a part to play’ – is even specifically aimed at this. At the same time, the university also has to deal with the tight labour market. Fewer and fewer candidates apply, but there are more vacancies than ever. As a result, about 10 percent of the vacancies currently remain unfilled.

In terms of student numbers, Van Krieken points out that Radboud University has been saying for years that it has no ‘growth ambition’.’ Years ago, we thought that it would not be desirable to have more than 20.000 students. Now we are almost at 25.000.’ He still sees programmes that could be ‘a bit bigger’, such as the teacher training programmes, but across the board the university is ‘on the larger side’.

‘Ten years ago, many pre-university students still went to higher education, but now almost everyone goes to university’

It raises the question of why the university does not hit the brakes. This has to do with the fear of inaccessibility of academic education. But even if the university were to close the door for students just a tiny bit, it would still run into practical difficulties. After all, educational institutions have few options for regulating their inflow. They can impose educational requirements, such as a certain high school course profile or grade averages for those entering university from universities of applied sciences (as is the case for the Law programme), but there is a limit. Also, a programme may not impose a numerus fixus just like that (see box).

According to Van Krieken, part of the solution to this problem lies elsewhere: in higher education. ‘Ten years ago, many pre-university students went to universities of applied sciences (hbo’s). Now, almost everyone enrols for an academic programme, at universities.’ This is a pity, Van Krieken thinks, because universities of applied sciences offer ‘very good vocational programmes. ‘I always tell upcoming students: “Think carefully. See what suits you best.” The fact that you did a pre-university study in high school, does not automatically mean that university is most suitable for you.’

Numerus fixus is no panacea

A numerus fixus is a maximum number of students who are admitted to a programme. Radboud University has six of those types of bachelors: medicine (330 places), dentistry (67), biomedical sciences (100), biology (220), psychology (600) and artificial intelligence (200).

The decision to impose a numerus fixus is not made lightly. After all, it makes education less accessible. Universities must be able to explain to the Ministry of Education why the quality of education would be at stake if they do not impose a fixed quota.

Nationwide, there will be 59 full-time university programmes with a numerus fixus next year. The maximum for medical study programmes is set by the Minister. For a large bachelor’s programme such as psychology, the universities make mutual agreements in order to prevent a waterbed effect.

Students who enrol in a numerus fixus programme must go through a selection procedure. By using a test or assignments, the programmes hope to admit the students who are most likely to complete the programme successfully.

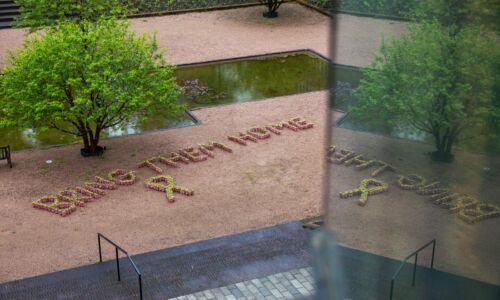

The university’s steady growth not only jeopardises the workload for staff and the quality of education. Last summer, the Executive Board was shocked by the problems on the student housing market in Nijmegen, which mainly affected international students. ‘The current student housing shortage took us by surprise,’ Van Krieken said at the time, after which he announced that emergency housing would be built behind the Huygens building. He hopes they will be built and finished in the next academic year.

Does the rector want to put the brakes on internationalisation so that these kinds of emergency measures will no longer be necessary? On the contrary. ‘As a whole, the university could be a bit more international. With about a quarter international staff, we are doing very well. But at some programmes the “international classroom” has not yet been reached.’

The idea is that a diversity of nationalities will boost the quality of education. Van Krieken: ‘Moreover, we also train students to work in an international manner. You cannot become an astronomer entirely in Dutch. The collaborations are international, you have to do your internships abroad.’

Like a can of sardines

Radboud University is hitting its limits on the subject of traffic and transport as well. Before the pandemic took hold of the university, it was busy on campus almost every weekday. Like a packed can of sardines on wheels, line 10 (the bus in Nijmegen that drives from the train station to the campus) would spit out masses of students on the campus, while a traffic jam of cyclists would form on Heyendaalseweg. People who dared to come to the university by car sometimes had to wait minutes before being able to take a turn right towards the Erasmuslaan. The pandemic has hidden these accessibility problems for the past two years, during which the university has grown once more.

The same applies to the pressure on university buildings and facilities. With the goal to relieve the workload of its staff, the university is actively seeking additional personnel. At the same time, workplaces on the campus are becoming increasingly scarce. At the Faculty of Science, student canteens have already been converted into offices and the floor area per employee has been reduced from 15 to 10 square metres. In the brand-new Maria Montessori building (social sciences), there already is a concern that the building is too small.

Before the pandemic, students complained mainly about a lack of study workplaces. And if they wanted to train with their sports clubs in the evening, they often did so at locations outside the campus. The Radboud Sports Centre cannot cope with the demand, and the possibilities for expansion have been exhausted. After years of daydreaming, students seem to have realised that there is no way that there is going to be an extra sports hall.

Achterhoek

In the long term, Rector Han van Krieken does see possibilities to relieve the pressure on the campus. ‘We need to think about offering education in other places than just on campus. Together with Maastricht, for example, we are working on plans to start a joint technical study programme in Venlo.’

He keeps a scenario in mind in which the campus develops as a place where mainly young bachelor’s students study together. ‘Very gradually, you see people going to work more often after obtaining their bachelor’s degree and then starting a master’s degree later in life. Those types of students have different needs.’

The university wants to focus more on ‘life-long development education’ – but according to Van Krieken, this does not have to be focussed on the campus. ‘In the Achterhoek (a region in the eastern part of the Netherlands, ed.), they would very much like to see us move parts of our education there. This might keep people from leaving the region. If public transport improves and you can get there in 45 minutes, why not?’

To make the physical campus future-proof, the Executive Board has been working for a long time on a so-called campus plan. A tricky issue, especially now the covid restrictions are being loosened, is the future of hybrid working. Will employees be able to clear out their home offices again, or will the future of working remain in private spheres, prompted by a pressing lack of space and the desire of some to work from home more often? This spring, the plan should be worked out and it should become clear how the university hopes to overcome the physical growing pains.