Men still earn more than women at university, even when doing the same job. But why?

-

Een promotie. Foto: Dick van Aalst

Een promotie. Foto: Dick van Aalst

Male scientists continue to earn substantially more than women at Radboud University. This is not surprising; professors are more often than not male. However, that is not the only explanation. Does prejudice against women also play a role?

Radboud University, according to its own slogan, contributes to a healthy, free world with equal opportunities for everyone.

And yet from 2015 to 2021, the pay gap between male and female scientists barely shrank. Men earned 13 percent more than their female colleagues in 2015; in 2021 it was still 12 percent. That amounts to a (gross) salary difference of 669 euros monthly.

Hierarchy

This is according to research by sociologist Babette Pouwels (Bureau Pouwels) published by the university last month. Pouwels was brought in by the university to take a closer look at the development of the pay gap, using the 2015 figures.

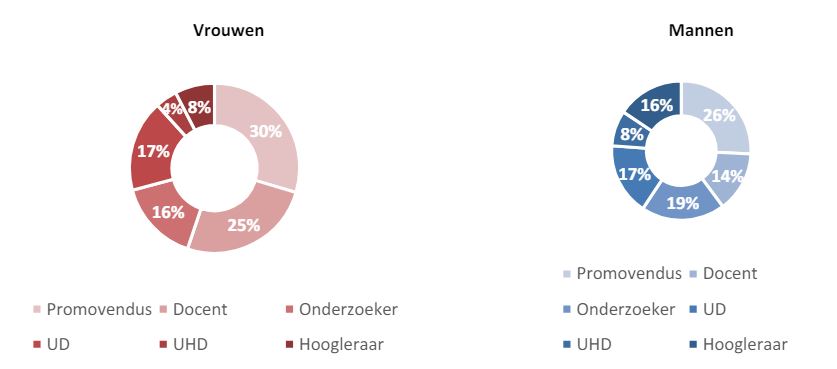

The pay gap can largely be explained by the fact that men are, on average, higher up in the academic hierarchy. Women continue to be heavily outnumbered in professorship (29 percent by the end of 2022).

But differences are also present if you zoom in on the so-called job categories (professors, associate professors, and so on). On average, the pay gap within job categories is 4 percent. Among professors, that gap has grown to 7 percent in recent years.

Temporary contract

According to Pouwels, special attention should be paid to teachers, a job category that is 61 percent women. These employees are much more likely than average to have a temporary and/or part-time contract. ‘There is hardly any career policy for these employees,’ Pouwels says. ‘As a result, advancement to higher positions stagnates.’

Another striking difference is in the allocation of allowances: a substantial number of scientists (a quarter of all professors) receive an extra amount in addition to their regular salary. This could, for example, be for special achievements. Women receive such an extra reward slightly less often, and when they do receive it, it is on average 15 percent lower.

Moreover, men are more likely to receive an allowance on unspecified grounds. Pouwels: ‘In general, we know that as soon as the criteria for getting an allowance are vague, inequality between men and women grows.’

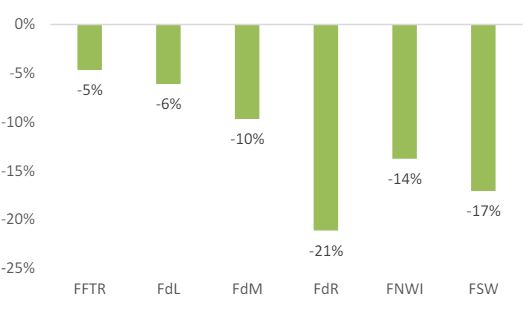

Not all faculties are the same. The pay gap at the Faculty of Law is 21 percent and at Philosophy, Theology and Religious Studies 5 percent. The other faculties range in between.

Not illegal, but undesirable

Pouwels emphasizes that her research is about pay differences, not unequal pay. ‘That is something different. Unequal pay is about different pay for the same work, which is prohibited by law.’

Pouwels’ research does not show that this is the case at Radboud University. ‘The fact that men more often work in higher positions and therefore earn more is not illegal,’ the researcher says. ‘But it is undesirable. It shows that there is gender inequality within the organization.’

‘Why does one employee get a promotion or an allowance, and not the other?’

It would therefore be good to dive deeper into the underlying factors that explain gender inequality at the university, Pouwels argues. ‘Why does one employee get a promotion or an allowance, and not the other? What criteria are used? Are those criteria neutral?’

To provide well-founded answers, a researcher would have to sift through individual personnel files and conduct qualitative research on them, according to Pouwels. This is the only way to examine whether prejudice and stereotyping play a role in the placement of employees in a particular position and scale.

If the criteria are unclear, they need work, reads one of Pouwels’ recommendations. A new European directive on pay transparency, which will come into force in the Netherlands in 2026, prescribes the same. From then on, employers must be transparent about rewards, the pay criteria they use, and the gender pay gap.

Structural solutions

Niels Spierings, professor of Sociology, was on the advisory committee of Pouwels’ study and endorses the need for further research on the pay gap at Radboud University.

He points out that there are still differences in pay between men and women that cannot be explained based on ‘neutral’ arguments, such as the overrepresentation of men in higher positions. ‘That is distressing to see.’ He looks at the -often poorly substantiated- allocations of grants with astonishment. ‘It’s a black box.’

‘Don’t put the responsibility on women but take structural measures’

If it were up to Spierings, the university would get to work to structurally solve the wage gap. ‘Think outside the box and don’t put the responsibility on women but take structural measures. For example, are we prepared to stop granting allowances? Or to abolish the distinction between Professor 1 and Professor 2 (which distinguishes professors with more and less experience with corresponding salary differences, eds.)?’

Not in a drawer

A new university project group focused on closing the pay gap is going to consider questions like these. The members met for the first time last week, led by HR policy advisor Joke Leenders,

The project group will be advising the Executive Board on how to drive the advancement of women to higher positions, how to improve grant criteria and processes, and how to promote monitoring and transparency. According to Leenders, all the recommendations Pouwels makes in her report will be considered. ‘We are going to see what those would mean for us in concrete terms.’

In addition, Leenders and her colleagues are going to prepare for the new EU legislation coming to universities. Among other things, that requires universities to report annually on the pay gap. ‘The question is how we can best set that up.’

According to Leenders, Pouwels’ research will not disappear into a deep drawer. ‘We are really going to work on it. But at the same time, decision-making processes simply take time. We want to do this very carefully.’ Before the end of the calendar year, Leenders hopes to come up with a plan of action.

Translated by Stella Kuipers