New tuberculosis treatment: ‘This disease eats people alive’

-

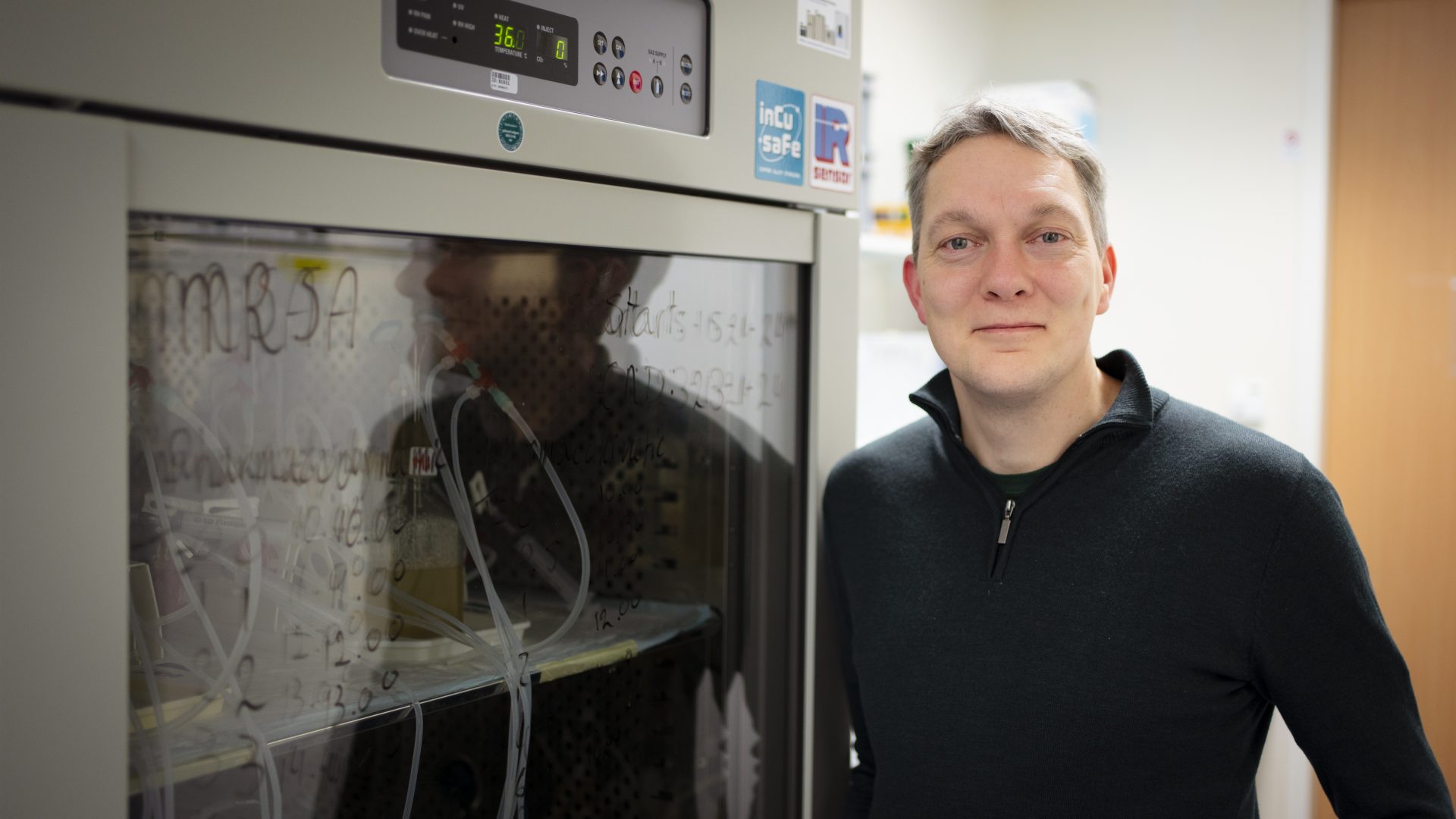

Foto: Johannes Fiebig

Foto: Johannes Fiebig

Every year, more than a million people die from tuberculosis. Because of its resistance to anti-biotics, a big part of its patients heal very slowly or not at all. Radboudumc has now started a new international study into the so-called bacteriophages as an alternative treatment for tuberculosis.

Viruses that infect tuberculosis bacteria with the intent to kill; doctor and microbiologist Jakko van Ingen hopes that these bacteriophages may soon contribute to successful tuberculosis treatments. Researchers at Radboudumc are part of a major, international study into combating the infectious disease.

Tuberculosis (TB) used to be known as ‘consumption’, as stated by Van Ingen, who leads the study in Nijmegen. ‘TB symptoms vary depending on which part of your body is infected, but this disease eats people alive.’ The researcher looks serious whenever he talks about the destructive nature of the disease.

‘There are large groups of TB patients for whom there are no effective antibiotic treatments anymore’

‘Patients can feel worn out and incredibly tired. If the lungs are affected, they may cough up a lot of mucus, sometimes even blood.’ Another classic TB symptom that Van Ingen mentions is the immune system getting so worked up that the patient is excessively sweating during the night. ‘And not just, “oh, I am sweating a little bit,” but the bed is completely soaked, multiple times a night. Patients also keep losing weight; there is no way of eating against it.’

Resistant to antibiotics

Van Ingen sees a lot of TB patients at the Radboudumc Expertise Centre for Tuberculosis. People come from all over the country to be treated there. ‘If their TB bacteria are resistant to conventional antibiotics, or if a patient cannot handle those antibiotics, they come to Nijmegen,’ as stated by Van Ingen.

The researcher explains that tuberculosis is usually treated with a combination of four different types of antibiotics over the course of six months. Antibiotics attack bacteria and are thus very effective against infectious diseases like TB.

Jakko van Ingen. Photo: Johannes FiebigHowever, various parts of the world started experiencing issues with antibiotic resistance in the nineties. ‘We have found new antibiotics for the more resistant TB strains, but the bacteria are becoming resistant to those as well. Because of that, there are now large groups of TB patients, for example in South Africa, for whom there are no effective antibiotic treatments anymore.’

Thanks to a million-euro grant by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, money has become available for a study on a potential solution to the resistance problem: bacteriophages. Van Ingen is in charge of the Nijmegen branch of the study, which is led by research institute TASK (South Africa). The other participants are the University of Pittsburgh and the Seattle Children’s Research Institute.

You mentioned that there are large groups of people for whom antibiotics are now ineffective. How many people are we talking about?

‘There are roughly ten million people worldwide who suffer from tuberculosis. About 200,000 of them have a very resistant strain of TB. That means there is no more effective treatment available to them. Next to that, there is also a group of people whose TB can still be treated with certain kinds of antibiotics, but the patients themselves cannot handle them due to allergies or side effects.’

And what does that mean, concretely?

‘It means those people will not be cured of the disease; a lot of them will pass away from it. And not being cured also means they run the risk of infecting other people.’

What exactly are bacteriophages?

‘Those are viruses that infect bacteria. Once a phage has settled inside a bacterium, it will multiply throughout the bacterium until it pops, like a water balloon. This then releases more bacteriophages which will hunt for the next bacterium.’

That sounds frightening. Couldn’t those viruses create a new, weird disease?

‘No, such a phage can really only take care of one specific sort of bacteria. It is a kind of matchmaking; a specific phage matches with one specific type of bacteria that it can infect and kill. It cannot do anything to other types.’

What gives bacteriophages the potential to be such potent TB treatments?

‘A downside to phage therapy is that, for many infections, you need to find the right phage to handle a specific type of bacteria. Some bacterium types have uncountable variants, or ‘strains’. But there is little variation amongst TB bacteria; all strains strongly resemble each other. That means one phage can attack a lot of different strains.’

‘We will administer doses of that phage cocktail for one week, and then we will keep daily track of the amount of bacteria still alive’

‘Researchers at the University of Pittsburgh developed a phage combination that responded to the most important strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. We think we now have a phage combination which we can use to treat most tuberculosis patients with. We are going to continue testing those findings.’

What will the research in Nijmegen look like for the foreseeable future?

‘The goal is to create a phage cocktail and use it to treat real patients. But before we get to that point, there are several things to check off, for example: how do the bacteriophages respond to the different conditions that TB bacteria can be encountered in? That is something we will test very meticulously in the lab.’

Can you give an example of such a condition?

‘For example, a TB infection can destroy someone’s lung tissue. The dead tissue becomes weak and acidic. We know that TB bacteria act differently in such an acidic environment. We will simulate those conditions in the lab and see if the phage therapy remains effective; will the bacteria still die if we set a specific bacteriophage on it?’

And what happens once you’ve checked all the boxes?

The next step will be a study on mice in Seattle. I am not a supporter of animal testing myself, but it is important in order to obtain approval to test it on TB patients. The first clinical trials involving humans will take place in Cape Town. At that point, the phage therapy will be a supplement to existing antibiotics treatments, not a replacement.’

‘We are not going to tell someone: “you do not need those antibiotics; we will just give you this little virus and it will all work out.” We will administer doses of that phage cocktail for one week, and then we will keep daily track of the amount of tuberculosis bacteria still alive in the mucus that patients cough up. If we can see a sharp decline, we know that the phages are effective and we can do further research.’

What scenario are you hoping for?

‘That the phage cocktail really works in human testing, thus creating a very cheap but effective treatment. They are just viruses; you can grow and make them available worldwide for little money.’

‘We can then say to those patients where it is really difficult to find three effective antibiotics for them, “well, for your tuberculosis, we only really need two good antibiotics, and we can use the phage cocktail as a third.” We can use those treatments combined to successfully treat TB.’

How many people would benefit from that?

‘That would probably be a hundred thousand people per year.’

Tuberculosis in the Netherlands: Wealth is the best medicine

Tuberculosis is one of the deadliest infections in the world, but at 700 cases per year, it is a rare sight in the Netherlands. Van Ingen: ‘most patients are migrants; often they are people we came to the Netherlands fairly recently from areas where the disease is more prolific.’

People with better housing and healthier diets are more physically fit, and thus more resistant to these infections. ‘In low- and middle-income countries, people are a lot more susceptible, and often also live much closer together. So, if one person gets a contagious form of TB, they are more likely to infect others.’

The quest for affordable and effective treatments is very important according to Van Ingen, but he feels that alleviating poverty should be the main goal. ‘In the end, wealth is the best medicine against TB.’

Translated by Jasper Pesch