-

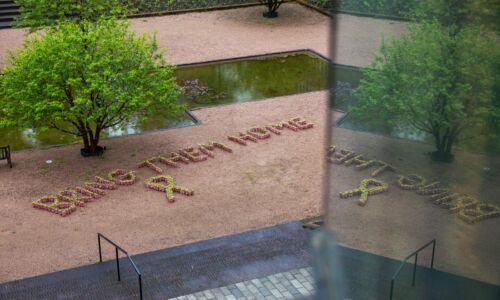

Een promotie aan de Radboud Universiteit. Foto: Dick van Aalst

Een promotie aan de Radboud Universiteit. Foto: Dick van Aalst

Making changes to the ‘Recognition & Rewards’ programme is a lengthy process, according to Jacqueline Drost, the new programme manager on this topic at Radboud University. ‘Rankings do not represent what we aim to assess. They therefore shouldn’t play a part in the evaluation of universities and researchers.’

Briefly put, the job of brand-new programme manager Jacqueline Drost (see insert 1) is realising the Radboud University’s vision for Recognition & Rewards onto the different faculties. To achieve that goal, Drost has to first meet with deans, researchers, and teachers.

Making changes to the Recognition & Rewards of academics is not something you’ll achieve today or tomorrow, according to Drost. ‘It’s about behavioural change, a different way of thinking, how you want to develop as a researcher and teacher.’

Recognition & Rewards is a broad term: it involves academic leadership, workload, work-life balance, yearly evaluations, et cetera. Which themes are your priority?

‘One of the most important themes is the trajectory of developmental paths, which is about how you want to develop as an academic. I also want to tackle the annual evaluation cycles, where tools are developed to see how we reflect on our performances. That includes how to lead such meetings: what kind of questions do you ask?

A lot of scientists have an ideal career path in mind: from PhD candidate to assistant professor, to associate professor, to eventually professor.

‘That’s why we need to adapt a different vision regarding academic work. We shouldn’t think solely in terms of promotions, but in terms of developments. We want to achieve that with four pillars – research, education, leadership, and impact – so scientists have the space to create their own profile with their capacities. That way, we can step away from the familiar traditional career ladder in the academic field. I hope that we will think less about promotion and more about development in the future. Not everyone has to become a professor – and maybe it’s way more fun not to do so.’

A significant number of scientists seem aware of the importance of Recognition & Rewards, but actually implementing changes seems to be less of a given.

‘That’s certainly true, it is really hard to change something. I’ve observed that it is unclear to a lot of people what Recognition & Rewards is and is not. That is why it’s important that we work together with the programme team in the near future regarding the question of what employees can expect from us. We hope that this will also make clear that our policy won’t just be implementing two or three actions.’

‘A cultural shift is a lengthy process. It is a change in thinking and behaviour. We therefore need to work in small steps, so people can notice that the annual meetings will be constructed differently, or that a different format will be used to assess performances. We should perhaps organise workshops or create formats for leading introductory or evaluation meetings.’

Scientists who teach often get less recognition than people who bring in the big research grants.

‘The way we think about recognising academic work has to change in that regard. You can create a model where education will be just as valued as research on paper, but if the way of thinking does not change with it, that belief will continue to exist. It takes a lot of time to change that. The recently released card game mmmAcademia also helps to encourage debates on that.’

‘Will only the number of publications be considered, or do we look more broadly?’

Universities remain competitive environments; big research grants partly fund them. Should that entire system be reformed before anything can change in the workplace?

‘The Dutch Research Council NWO plays a big part in the nationwide A&R programme team. They also concern themselves with how to assess a researcher’s curriculum vitae for a grant application. Will only the number of publications be considered, or do we look more broadly?’

Who is Jacqueline Drost?

Jacqueline Drost is very familiar with Radboud University: she worked as a PhD candidate and assistant professor at the Nijmegen School of Management between 2014 and 2020. Afterward, she completed her dissertation about rankings in the academic field and healthcare sector, titled The Irony of Rankings, at the University of Twente (see insert 2).

How does Radboud University perform regarding Recognition & Rewards compared to other universities?

‘I know from conversations with nationwide A&R project leaders that some universities, like the University of Twente or Maastricht University, have already actualised their developmental paths trajectories. They are also quite far in the process of implementing the new format for the annual evaluations. We are not that far yet. We intend to work together with other universities to learn the best way of bringing Recognition and Rewards into practice.’

How can you assess if the actions regarding Recognition & Rewards reach the workplace?

‘I would say, taking from my PhD-research (see insert 2, ed.): I don’t think that this is something that we want to assess. It is more important that the scientists within the faculties discuss Recognition & Rewards. Currently, we are also setting up a steering committee with representatives from different faculties. That is a better way to implement change.’

Not a fan of rankings

Jacqueline Drost is very critical of university rankings, such as The Times Higher Education Ranking or The Shanghai Ranking. She completed a dissertation about this topic at the University of Twente.

Drost’s issue with rankings starts at the methodology. She states that rankings often only include measurable aspects. She provides an example: ‘Think of Tripadvisor, an app that assesses the quality of restaurants. They look at the number of chairs, the price of the food, et cetera. Characteristics that aren’t measurable but are still of importance, such as the freshness or sustainability of its products, are not included in the system.’

Rankings can have a lot of unintended consequences for university as well, according to Drost. ‘They make different decisions based on that. In some rankings, the quality of a university is measured based on the number of students that have a job after graduating, so universities created departments to help alumni get a job.’

But rankings can also affect individual researchers, Drost states. ‘For a long time, academics from one of Radboud’s faculties were judged based on the number of publications tied to their name, up until two decimals. On the one hand, that system wants to stimulate multidisciplinary research. However, whoever collaborated with multiple researchers got fewer publication points. As a result, researchers started to strategically look at how to get the most points. In that way, the rankings influenced the content of their work.’

That is exactly why Drost does not believe in rankings. ‘They do not represent what they aim to assess. They therefore shouldn’t play a part in the evaluation of universities and researchers.’

Translated by Milou Aluy-van der Meij