One year after the invasion (3): In the Huygens building, Boris Ivanov is not reminded of war

-

Boris Ivanov. Foto: David van Haren

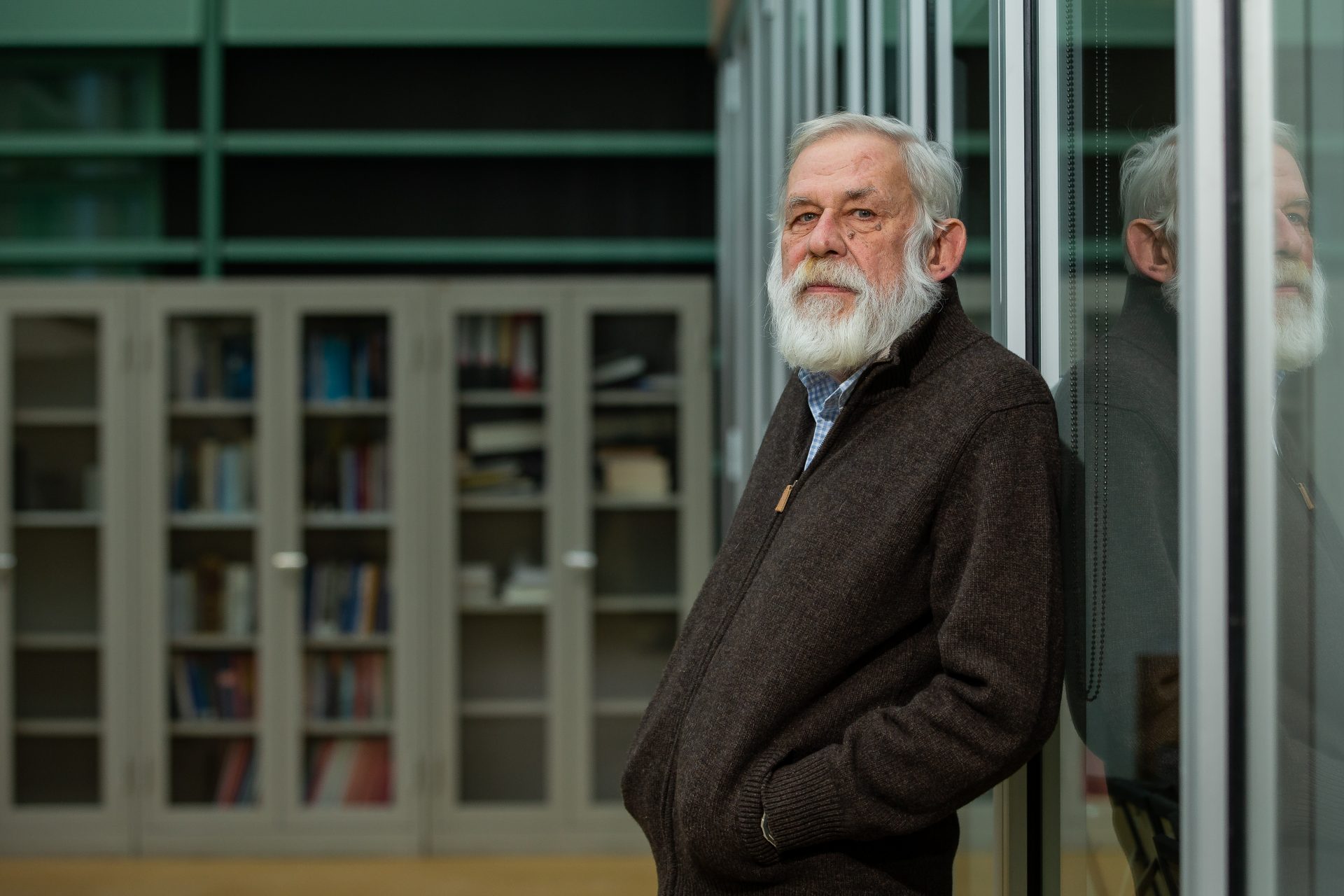

Boris Ivanov. Foto: David van Haren

In the middle of March last year, Professor Boris Ivanov (74) fled from Kyiv to Nijmegen in a hurry. Born in Soviet Siberia, the Ukrainian physicist had been living in what is now Ukraine since he was fifteen. Since his flight, Ivanov has been a guest researcher in his colleagues’ department in the Huygens building.

They were lucky that their Kyiv apartment had walls full of books, Boris Ivanov says with a grimace. He and his wife could use them to fill the window frames when the Russian invasion started. City officials had ordered civilians to protect the windows, in case the city streets became a battle ground. Dostoyevsky – ‘One of the greatest writers of all times’, according to Ivanov – proved not only to be good for the mind, but also good protection against bullets.

When he and his wife fled early last year, the 74-year-old Kyiv University physics professor was not sorry to leave their personal library behind. Taking books was not an option anyway: clothes took up all the space in their two suitcases. Ivanov only snatched a hand-sized bronze Buddha statue (a miniature version of a famous statue in Kamakura) from their mantelpiece just before leaving, a memento of his multiple visits to fellow scientists in Japan.

Survival strategy

Via Lviv, Poland, and Germany, the Ivanovs ended up in Nijmegen, in an apartment within walking distance of the campus. Since then, the physicist has been working as a guest researcher in the solid-state physics department. There, in a homely sitting area on the first floor of the Huygens building, he tells how his life has been radically turned upside down since last year.

One year after the invasion

On 24 February, it is exactly one year ago that Russia invaded their neighbouring country Ukraine. In a series of articles on Vox, students and employees talk about how the war has become a part of their life.

Ivanov speaks softly, with Russian-accented English. His wild white beard makes him resemble the stereotypical image of a scientist. The professor regularly laughs a little – humor and putting things into perspective seem to be his way of lightening the gravity of current events. Impossible according to the laws of physics, but indispensable as a survival strategy.

Why did you come to Nijmegen?

‘A few years ago, Theo Rasing and Alexey Kimel (Nijmegen professors of physics, ed.) invited me here, via the Radboud Excellence Initiative. I have been working with them for a long time: our first joint publication dates back to 2009. And Dmytro Afanasiev, who is an assistant professor here, was once my student in Kyiv. Because of corona, that visit was canceled at the time, but now they invited me again. I feel at home here because of my friends at the department and the European atmosphere.’ Laughing: ‘More than in the United States. On some university campuses there, you need to travel 6 miles before you’re allowed to smoke.’

What was the moment you decided to flee?

‘At first I didn’t really feel any danger. The war did not start just last year, but in 2014 (in Donetsk, Luhansk and Crimea, ed.). That the Russian army also invaded the rest of the country was surreal. At one point, the atmosphere on the street became increasingly grim. There were people that were carrying guns. It was unclear if they were military or not – they were wearing no uniform. It felt unsafe, especially to kids, like our grandson. Then we decided to flee. Our son drove all of us to Lviv, from where we took the bus to Poland. He himself could not leave the country, only men over the age of 60 are allowed to do so.’

Biography Boris Ivanov

Boris Ivanov (1948) was born in Khabarovsk (Soviet Union, present-day Russia), a stone’s throw from the Chinese border. As a child, he moved to Novosibirks with his parents. At the age of fifteen they came to Kharkiv, Ukraine. There, Ivanov went to university, where he obtained his doctorate in 1983. Since then, he has been working in Kyiv, currently at the Institute of Magnetism of the Ukrainian National Academy of Sciences. Boris Ivanov is married, has a son and a grandson. One of his nieces is Tatiana Lazareva, a Russian TV presenter and vlogger who regularly criticizes Putin’s regime.

How are your son and other family in Ukraine doing?

‘Fortunately, he hasn’t had to fight yet, because he works for a United Nations organization. For a long time already, this organization has helped refugees from regions like Asia and Africa with legal issues in Ukraine, to protect their human rights. Now, of course, they are working mostly with the problems caused by the war. Aside from that, I have no direct family in Ukraine. My parents passed away 30 years ago, my sister and brother are unfortunately no longer here either.’

Your cultural background is Russian, and this is also your native language. Does that complicate the current situation?

‘Politically, Ukraine has been sandwiched between Russia and Poland for centuries, between the Orthodox and the Catholic spheres of influence. Because of my background, I have never felt a strong difference between Ukrainians and Russians. Many Ukrainians have Russian relatives and vice versa. I also taught in Russian at university. I think less clearly in another language (laughs).’

‘Those things like language were never a problem in the past, but now they are. You see that monuments of Russian artists are being destroyed in Kyiv, like that of the famous poet Pushkin. But also the Russian literature is completely removed from the school program. It is an extremely sensitive subject, which is why I prefer to avoid discussions about it.” He says, jokingly: “They might still shoot at our apartment, because of the Russian authors of the books in the windows.’

‘Moving to Russia during the war would feel wrong to me’

Given your background, have you ever consider fleeing to Russia?

‘I cannot even imagine moving to Russia during the war. It would feel wrong to me. From my childhood I learned that there is nothing worse for a man than to be a traitor.’

Ivanov is a professor of theoretical physics and specializes in solid state physics. He is a member of the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences, the country’s most important research organization. Also internationally, Ivanov is among the top scientists in his field, says physics professor Theo Rasing. Ivanov has collaborations worldwide, including several European countries, Japan and the USA. He regularly publishes in leading journals such as Nature Physics and Science – sometimes collaborating with Nijmegen scientists.

His research is about magnetism, or a bit more specifically: about how the properties of atoms in a material change when you make them magnetic. In particular, Ivanov does a lot of work on the so-called spin of atoms, simply put: their direction of rotation. Rasing: ‘His books on this topic are among the first I recommend to PhD students.’

You are still doing research, even though you are already past the retirement age.

‘Yes, it is part of my identity.’ Chuckling: ‘Besides, I was elected as a member for life of the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences, so I have to keep going. That is also easy as a theoretician. I don’t need much more than my notepad here and a pen. That was a blessing in disguise when I had to flee.’

Does theoretical research become more difficult as you get older?

‘When you are young, you are more powerful. Your brain then works faster and you are also braver. When you’re older, on the other hand, you have more experience. As a result, I see analogies with other disciplines more quickly when I am working on a problem. And the nice thing about doing research for a long time is that I now see some of my theories finally being proven experimentally, because the necessary equipment simply wasn’t there before.’

‘Work is a good distraction from bad events’

What is currently happening with the science in Ukraine?

‘Everyone is depressed, but the research is going on as much as possible, especially theoretical work. Many experiments have come to a standstill, as has education. But my friends in Kharkov are still issuing the physical journal that they publish, Low Temperature Physics. Work is also a good distraction from bad events, otherwise you will go crazy. A couple of years ago, a close friend of mine, who is a mathematician, lost a dear friend of his. He asked me: “please try to find a good problem for me.” I am also trying to follow that advice now here.’

How do you see the future?

‘My life has suddenly changed 180 degrees. Suddenly I live here in Nijmegen, at the age of 74, with an uncertain future. My wife in particular has a hard time, she doesn’t have that distraction from work. It is very difficult for her that she cannot see our son. She is also a physicist and she still has small collaborations with her colleagues at the Institute of Physics in Kyiv. She also reads a lot, but you can’t do that 24 hours a day.’

‘I don’t see how this conflict can be brought to a good end as weapons continue to be built up on both sides. Sometimes I dream that the war is over. But I think that is only really possible if there is a treaty that guarantees everyone’s safety.’

Energy-efficient hard drives

Ivanov’s research into magnetization could lead to energy-efficient computers. For a simple example of magnetization, think of a pin that you want to use as a compass needle by floating it in a cup of water. You can magnetize such a needle by moving a magnet over it several times. All iron atoms in the needle then point in the same direction, as it were, instead of in random directions.

Magnets can control the spin of atoms in a similar way, the professor explains. You can theoretically use that ‘direction of rotation’ as the ones and zeros (computer bits) of an energy-efficient and stable type of hard disk. Such a hard disk then does not require any moving parts, as opposed to the current disturbance-sensitive ones in our computers. They can also become much smaller and work much faster. Ivanov: ‘The challenge is to get it to work in practice – but that’s up to experimentalists and engineers, not me.’