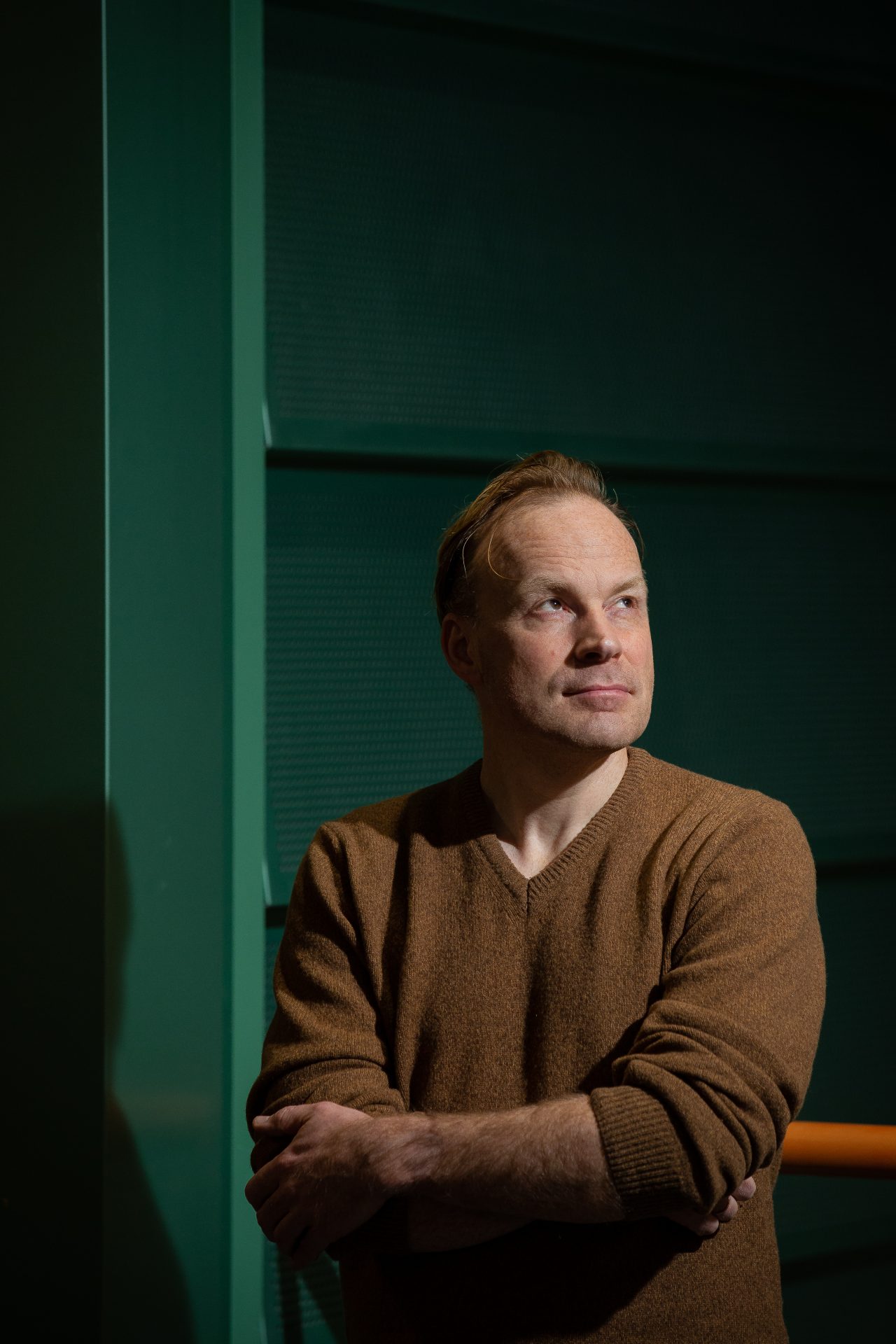

One year after the invasion (5): Professor Alexey Kimel keeps visiting his parents in Saint Petersburg

-

Foto: David van Haren

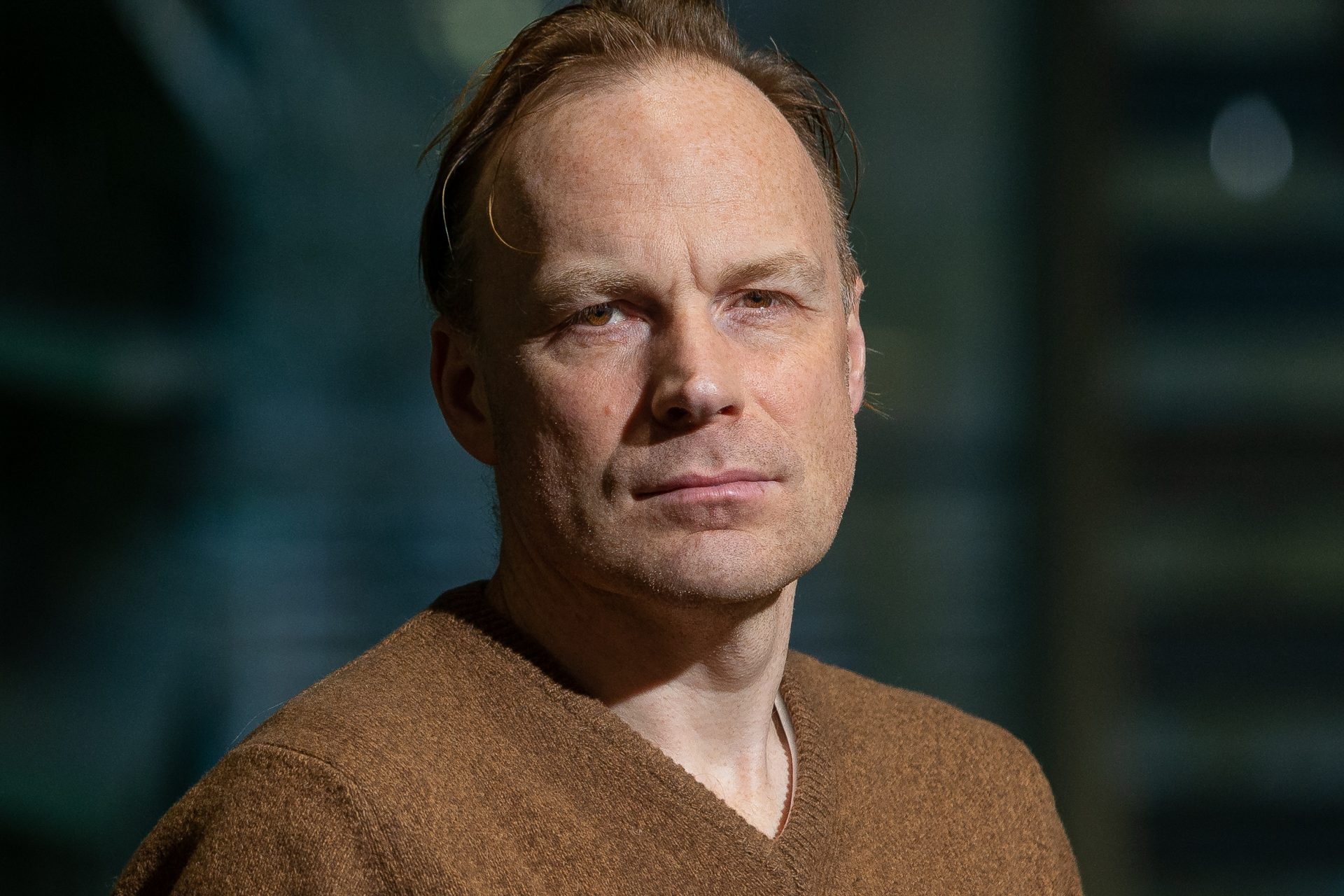

Foto: David van Haren

Despite the war in Ukraine, which he finds awful, Alexey Kimel remains proud of his Russian heritage. In the last year, the professor of experimental physics travelled to Saint Petersburg five times to visit his parents, among other things. ‘I want to show my children that not all Russians are angry or dumb.’

Two days after Russia’s large-scale invasion of Ukraine, on 26 February 2022, Alexey Kimel is on a plane to Saint Petersburg. Shortly before landing, the professor of experimental physics notices the plane making a strange turn. Some time later, the captain announces that he has been asked to fly back to the Netherlands.

‘I can talk about it light-heartedly now, but at the time it did make me feel tense’, says Kimel in his office in the Huygens building. A chalkboard with mathematical formulas hangs on the wall.

Kimel’s trip to Saint Petersburg had been planned for a while: after a busy period at work, he was supposed to visit his parents in Saint Petersburg, among other things. ‘At the check-in, I was asked whether I wanted to travel to Russia’, says the professor, speaking and thinking in fluent Dutch. Only every now and then does he have to think about the wording of a sentence, given the sensitivity of the subject.

‘If politicians took the weekend off, it would be doable, is what I thought.’ Kimel’s plan was that he could always travel back to the Netherlands via Finland, if his return flight was cancelled. But European politicians did not take the weekend off. As it turns out later, the decision to not land in Russia was part of the first sanctions package against Russia.

Big shock

When asked whether his life has changed in the past year, Kimel replies that life has changed for everyone. ‘The invasion of Ukraine was a big shock, even for us. It had been going this way for eight years, but the invasion came faster than everyone thought.’

In 2002, the professor emigrated to the Netherlands. Together with his wife and two daughters aged 9 and 19, he lives in a Vinex neighbourhood in Malden. Because it took a lot of effort in the Netherlands to apply for a new passport each time, Kimel renounced his Russian nationality 15 years ago. A pragmatic decision, he calls it. ‘In reality, I remain Russian.’

One year after the invasion

On 24 February, it is exactly one year ago that Russia invaded their neighbouring country Ukraine. In a series of articles on Vox, students and employees talk about how the war has become a part of their life.

What’s happening in Ukraine is on Kimel’s mind every day. ‘Many people living in Moscow and Saint Petersburg have relatives in Ukraine; the war is driving through their families like a tank. Brothers living in Moscow and Kyiv no longer speak to each other. How can it be that people who have so much in common and speak almost the same language shoot each other, purely because they think differently? I just can’t understand that.’

Kimel himself, he says, was born and educated in the Soviet Union before the fall of the Wall. At school, he learned that the Soviet Union’s strength was friendship between peoples and that all people were the same. He fears that young people today are growing up with different values because of the war. ‘A human life is worth almost nothing anymore. If you grow up in such a climate, there may also be more violence in the future.’

Academic freedom

At the end of 2021, the world still looks very different. Together with a group of scientists from Russia and the Netherlands, Kimel is meeting at Moscow State University to discuss far-reaching scientific cooperation between the two countries. The Dutch ambassador is present, as are representatives of OCW, NWO and the Russian Science Foundation. Kimel shows a booklet he compiled for the occasion. Its title: Heritage, challenges and perspectives of scientific collaboration between Russia and the Netherlands.

In the past, there were joint funding programmes for science in the Netherlands and Russia, Kimel explains. ‘Those resulted in several Spinoza Prizes. The Nobel Prize for Physics in 2010 was also a result of cooperation between the two countries.’

Because of the war, all the work has been for nothing: on 24 February 2022, the booklet might as well be thrown in the trash. Official collaborations between European and Russian universities have since been frozen. ‘It’s catastrophic’, says Kimel. ‘All ties have been cut.’ Yet he still keeps informal contact with scientists in Russia, Ukraine and the rest of the world. ‘The world has changed, but those people are still the same.’

Working in Kimel’s department is a Ukrainian lecturer whose mother lives in Ukraine. ‘It is a difficult time for him’, he says. ‘We can only offer him our support. I think it is a great victory that we continue to work as a team and respect each other. For our department, it is important that we remain neutral. We used to discuss politics sometimes, but we can’t do that now. It gets emotional too quickly.’

Remaining who you are

In June 2022, Kimel crossed the Russian border again for the first time in a while. But not on a direct flight as before: in Helsinki, he travelled by bus, which took seven hours to get to Saint Petersburg. Since then, he has been to Saint Petersburg five times and twice to Moscow – with his children in the summer. `I found it important to show them that ordinary people also live in Russia who deal with exactly the same problems as here. also It also allowed them to visit their grandparents.’

Discussing the war with his very elderly parents is not easy, Kimel says. ‘They watch Russian state television and don’t understand why Europe has turned on Russia. Of course, they are curious about what is happening in Europe. I have to explain to them that many Ukrainian refugees are hosted here, that it is not super cold in our house and that we can use hot water whenever we want. But the first thing my parents always ask us is if everything is okay with us.’

‘Of course my parents are curious about what is happening in Europe’

Because of European sanctions, it is no longer possible to watch news broadcasts on Russian television, says the professor. He cannot prevent his children from watching Dutch television and talking about the war at school. ‘At home, we also talk to them about the war’, he says. ‘And in Russia, they could see for themselves that not all Russians are angry and dumb and only think about how they want to invade other countries.’

Still, Kimel is happy that children deal with the situation differently from adults. ‘ There is a girl at my youngest daughter’s school who fled from Ukraine. My daughter sometimes translates things for her. I don’t think they talk to each other about the war.’

Lethargic and lacking initiative

Do people react differently to him since the Russian attack in Ukraine, given his Russian background? Initially, Kimel says no. ‘On the contrary. My neighbours sometimes come and ask me for additional explanations when they have read an article in the newspaper that they don’t quite understand. Although I can’t say I haven’t noticed anything at all either.’

The professor hesitates for a moment, then pulls an article from his bag that appeared in a local Molenhoek newspaper in March. The piece, titled “Differences and similarities between Europe and Russia”, announced a cultural evening. “Although a Russian and a European do not differ much in appearance and there are also similarities in cultural history, we often find Russians lethargic and lacking in initiative,” the text reads. “In this evening’s lecture, we will be taken through time and learn how Russia’s various rulers promoted this behaviour.”

Kimel says, he was bewildered while reading the article. He sent an email to the organisers of the event, to the municipality and to the newspaper’s editor. He received apologies from the organisers, but he has heard nothing from the newspaper. According to the municipality, the article fell under the newspaper’s freedom of speech. ‘I don’t think the same argument would be used if politicians from FvD or PVV said this about Moroccans or Jews’, Kimel says.

Dostoevsky

It sometimes seems different in European media, Kimel says, but no one in Russia likes the war. Last summer, he and 10,000 other runners took part in a 10-kilometre race in Saint Petersburg, while wearing a Nijmegen Athletics T-shirt. ‘Nobody was shouting patriotic slogans, which you see in football matches, for example. In a way, it was advocating peace.’

When Putin announced the mobilisation in Russia, European media showed images of long traffic jams at the borders with neighbouring Georgia and Finland as men wanted to flee the country. That picture is incomplete, according to Kimel: many of these Russians have since returned to their homeland. ‘Once abroad, they realise they are Russian. If you don’t have a job or a decent income, who are you?’

For Russians who have fled and suddenly become very critical of their homeland, Kimel has no sympathy. ‘Suddenly they are ashamed of their nationality. I don’t understand that.’ Distancing himself from his own people is something the professor cannot do. ‘When you do that, you distance yourself from your God’, he quotes Dostoevsky. It is a phrase he often repeats to himself since the war broke out. ‘Such terrible things are happening in Ukraine, but they are still my people.’

‘Of course, I am not proud of what is happening in Ukraine’

Despite everything, Kimel still feels proud to be Russian, he says. ‘Of course, I am not proud of what is happening in Ukraine. But all countries do things that their citizens can feel ashamed or proud of.’

What does make him proud: his roots and his education at a Soviet school. Russian music, literature, and science. ‘I am currently reading letters by Pyotr Kapitsa (Russian physicist and Nobel laureate, 1894-1984, ed.). They were written in the 1930s, not long after the civil war (war between the Red and White armies, 1917-1922, ed.). People shot at each other; they reported their neighbours to the police. Despite that terrible time, Kapitsa continued to defend science and his worldview.’

Escalation

The war has now been going on for a year, with the European Union imposing more and more sanctions on Russia and supplying ever stronger weapons to Ukraine. Does it worry Kimel that the relationship between the EU – and thus also the Netherlands – and Russia is getting colder? ‘That must be a tense development for everyone, not just me’, he says. ‘It’s just a continuous escalation, I don’t see where it ends.’

Still, despite rising political tensions, Kimel does not see himself returning to Russia any time soon. ‘So far, there has been no reason to think about that’, he says. ‘In my immediate environment, there has been a lot of understanding since the first days of the war, including from the Executive Board, the dean of our faculty and the director of our institute. My academic freedom is well protected. But if one day that is no longer the case or if my family no longer feels safe in the Netherlands, I do not rule that out from happening.’

Translated by Jan Scholten