People in their thirties as an object of study

-

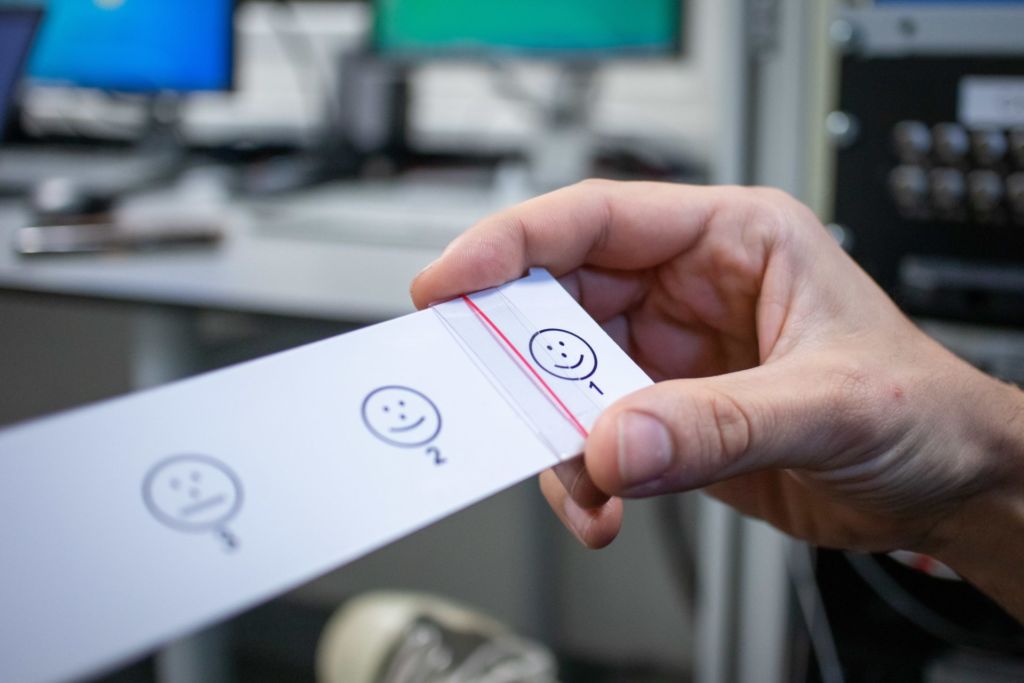

Onderzoek in de MRI-scanner. Foto ter illustratie. Fotograaf: Rein Wieringa

Onderzoek in de MRI-scanner. Foto ter illustratie. Fotograaf: Rein Wieringa

A better understanding of how people function in their daily life. That’s the goal of the Healthy Brain Study, a large-scale study involving one thousand thirty-somethings from Nijmegen and surroundings. VOX editor Ken Lambeets (32) enrolled as a test subject, spent a week covered in activity monitors, and took part in a test day at the Trigon.

In a small office in the basement of the Trigon on the Kapittelweg, I slowly immerse my right hand into a bowl of ice-cold water. As my fingers slowly stiffen, a research assistant makes an ultrasound scan of my carotid artery, using a device normally associated with the bellies of expectant mothers. In the meantime, a camera records the effect of the ice-cold bath on my face. What’s the purpose of this test again?

Fireworks

It’s a question I ask myself a lot on my first test day at the Donders Institute. While I lie in an MRI scanner staring for ten minutes at a small cross on the screen above me. During a computer test which involves me getting small electric shocks. During the three times three minutes chewing on a cotton swab. Or when I’m asked to use a joystick to hit one ball with another, following which fireworks erupt on a digital screen while a robot arm pushes the joystick back to centre.

Granted, most of the tests are fun and painless, but research assistant Vivian Heuvelmans is not likely to answer my questions any time soon. The answers will come later this year, she promises, after the third of the three test days. Too much prior knowledge might influence the research results, and that’s not allowed.

The tests are part of the Healthy Brain Study (HBS), a large-scale study conducted by Radboud University, Radboud university medical center and the Max Planck Institute on one thousand thirty-somethings from Nijmegen and surroundings. The study, which was launched last September, costs € 7.9 million. Over half of this money, € 4.4 million, comes from the Stichting Reinier Post, which manages the finances of the Stichting Katholieke Universiteit. The remaining € 3.5 million is funded directly by Radboud University.

The HBS is intended to generate a gigantic database, to be used by researchers from various disciplines. The ultimate goal: more insight into the workings of the brain and how it impacts our daily life. A crucial topic, especially since researchers still have very little idea of how this interaction works. The goal of the HBS is to help them make progress on this matter.

Artificial

Why do people in their thirties make such interesting test subjects? Principal investigator Guillén Fernández from the Donders Institute calls them a relatively stable age group. ‘Their brain is fully developed, but not too old yet,’ explains the Hispano-German Professor at his standing table at the Trigon. ‘People in their thirties often face important decisions about their families, careers or economic status: Should they buy a house or not? We want to find out how all these decisions impact people.’

HBS is unique in terms of its scope and duration. Most scientific studies test specific hypotheses in small groups. But this method has its limitations. Lab studies are always a bit artificial anyway, and the number of test subjects is too small to identify individual differences. And that while the brain is our most individual organ. In addition, experiments usually only last one day, after which the test subjects – often students – go home. ‘This kind of controlled environment makes it easy to test hypotheses, but as a setting, it’s far removed from everyday life,’ says neurologist Fernández.

This is why the one thousand HBS participants are required to wear activity monitors for three weeks during a period of one year and take part in three test days at the Trigon. Stepping outside the controlled environment makes it possible to investigate how people feel when they’re hungry, stressed, or tired. ‘Our brain behaves differently at moments like this,’ says Fernández.

In July 2022, researchers will finally get access to the 90 terabyte or 500,000 hours’ worth of data the study is expected to produce, though it’s not entirely clear yet how the data will be shared with the rest of the world. In all probability, the database will be released in three phases: in the first six months exclusively for the researchers who were involved in the study design, then after six months for the rest of Radboud University. After one year, researchers from other universities will be granted access to the data, presumably on a subscription basis.

53 hours

The difficult task of finding one thousand test subjects in the area between the Rhine, the Maas, the A50 and the German border rests on the shoulders of Janet den Hollander, the marketing expert hired specifically for this project. The panel should consist of 50% men and 50% women and form a representative cross-section of the population.

What do participants get?

Participants in the Healthy Brain Study can earn a total of € 200: € 50 for each of the three test days and another € 50 for performing computer tests. The total amount is paid at the end of the study. Participants also receive feedback on some of the measurements, such as blood pressure. Intelligent scales teach them more about their lifestyle. Those who are interested can also get a photograph of their brains.

This in itself is a major challenge. Participants are required to devote about 53 hours spread over one year to the study, and people in their thirties are often busy with their career, family and social life. In her efforts to secure enough test subjects, Den Hollander was inspired by the Rhineland Study, a large-scale health study in Germany. The study’s organisers were able to convince companies to give something back to society by giving their employees a day off to take part in the study. ‘We’re trying to get local companies to do the same,’ says Den Hollander.

The method seems to be working. To date some three hundred people in their thirties have signed an enrolment form, and 96 are already taking part in the study. Of the six people who have dropped out, four found the study too demanding. ‘This is why in our communication we now place even more emphasis on the time investment,’ says Den Hollander.

Sleep headband

It’s no exaggeration to say the study requires a lot from the participants. One week before the test day at the Donders Institute, a courier on a bicycle appears on my doorstep. He hands me a large box containing four activity monitors and a computer.

A moment later I’m attaching a small exercise monitor to my right thigh. The device measures how much time I spend sitting, standing and walking. An hour later, I’ve already forgotten it’s there. The same applies to a silicon bracelet on my wrist that registers what substances I come into a contact with, and a smart watch that keeps track of things like my heart rate and body temperature.

A trickier item is the sleep headband, which measures sleep depth and intensity. The first night I wake up a few times and can’t get back to sleep again due to the faint glow of the LED light. After a few nights it gets better, though I’m not sure whether this is due to my getting used to the strange device on my head, or simply the fact that I’m just tired. Makes me wonder how representative these data are of how I normally sleep.

But the most annoying thing are the questionnaires I get ten times a day via an app and that take approximately 2.5 minutes to complete every time. What am I doing? Who am I in contact with online? Do I feel appreciated by the people around me? Am I able to concentrate? With regard to the last question: Usually, yes, until I get one of these annoying notifications.

Finally, there’s some maintenance and administration work required to take part in the study. The sleep headband has to be charged every day, as does the watch, and I have to transfer data from these to a computer. When this fails to work on the first evening, I call the helpdesk, which turns out to be only contactable by telephone during office hours, so I send them an e-mail. In the end, it all works out fine.

Still, as the test week progresses, I find myself wondering repeatedly why I decided to take part in this study. The monitors and tests make it feel like a major medical check-up, but I won’t be getting any personal reports. The odds of failing one of the memory tests or the cycling test are in principle very low. All data are anonymised, so for the purpose of the study I’m just a long code. Yet I catch myself trying to do my best on all measurements and tests. And when I can’t poo on the evening before the test day – participants are expected to bring a faeces sample to the Donders Institute – I’m even a little upset.

Football World Cup

In the end, it probably boils down to vanity: my wanting to be part of a study that leads to a scientific breakthrough. And I’m not alone in this. So far, 132 of the 300 enrolled test subjects indicate that their main reason for taking part in the study is to make a contribution to science.

This is interesting, because the real research questions about the HBS data haven’t been formulated yet. If you want to investigate the study data, you have to apply for a grant. And the costs of using the data can be considerable. As part of the study, three thousand blood samples will be collected (three per participant), so if you want to study protein in the blood, you’ll have to raise a lot of cash.

In funding the HBS, Radboud University wants to support interdisciplinary research. Researchers working on the data have to think in broader terms than their own discipline. This also applies to the neuroscientists themselves. ‘A language researcher looks at language and a memory researcher at memory,’ says Fernández. ‘Sometimes their results overlap, and they’re not even aware of this. Because this data set is so big, for the first time we’ll be able to see interactions between different research areas clearly.’

Team science

HBS hopes to play a pioneering role not only in the study design itself, but also in how scientific research is conducted. ‘At present science involves far too many small research groups,’ says Fernández. ‘This model dates back to the 19th century, a time when there were only a few hundred researchers in Europe. Today there are more than one million researchers worldwide, and the problems we are looking at are too complex to be answered within a single research group. Faculties are very old-fashioned structures.’

The neurologist refers to HBS as an example of team science. His dream is that all publications arising from the study will bear the signature not of individual researchers, but of the Healthy Brain Consortium. He’ll probably have to compromise, and the names of the researchers performing the analyses will appear under the publications alongside the Consortium’s name.

The data set is so big, in fact, that it can potentially be used not only by neuroscientists and medical experts, but also by researchers in science, communication sciences, social sciences and management. Fernández believes that by combining areas of expertise, and jointly analysing data from various disciplines, we can gain a better understanding of how people function in their daily life – for example how economic decisions are made. Historians can in turn use the database to investigate how historical events – a terrorist attack, a financial crisis or the Football World Cup – affect the brain.

Nobel Prize

It’s not something you usually think about, but a study that costs this much money and effort can also fail. ‘We may not be able to find enough test subjects, but I’m feeling more optimistic about that these days,’ says Fernández. ‘Or participants might find the study too stressful and give up after a while, although we try to support them as much as we can in the process. Another risk is that our measurements turn out to be less useful than we’d hoped or that the data are not of sufficient quality. Finally, participants might find the tests too difficult, or researchers might not be interested in analysing the data.’

Whether the Healthy Brain Study will ultimately lead to a scientific breakthrough is therefore a matter for speculation. Fernández hopes the study will lead to new insights about the brain, an organ we still know very little about, despite decades of research. This is one of the reasons so few Nobel Prizes are awarded in Neuroscience. But if one of them ever goes to the researchers behind the Healthy Brain Study, I will know for sure: I didn’t spoon my poo into a jar in vain.

Participants wanted

More subjects in their thirties are needed for the study. For more information and to enrol, go to www.healthybrainstudy.nl.