Radboud University: from social mobilizer to sustainability guru

-

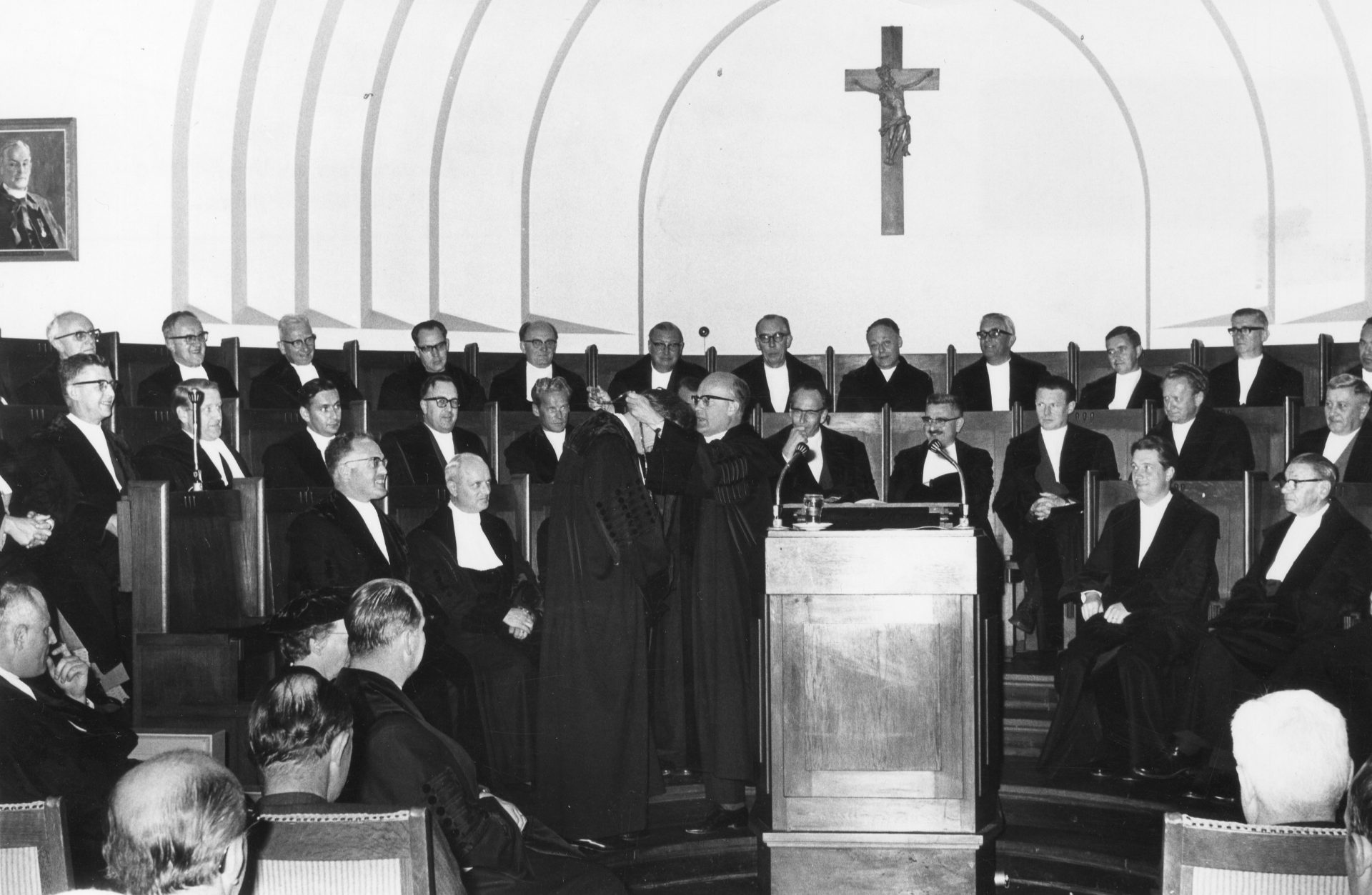

Bij de viering van het eerste lustrum, op 17 oktober 1928, deden studenten tijdens een rijjool het hoofdgebouw aan het Keizer Karelplein aan. Foto: KDC Nijmegen

Bij de viering van het eerste lustrum, op 17 oktober 1928, deden studenten tijdens een rijjool het hoofdgebouw aan het Keizer Karelplein aan. Foto: KDC Nijmegen

Once founded to uplift the Catholic population, Radboud University is searching for a different identity in the run-up to its centenary. Sustainability is the new holy grail. How can this new direction be reconciled with the University’s history as an emancipation university?

New Vox

This story is part of the new Vox, which can be found on campus this week. In this Vox we dive into the history of the 100-years old university and look towards its future.

As if the Netherlands had won the World Cup, that was what it must have felt like in Nijmegen’s city centre on 17 October 1923. Catholics from all over the country had travelled to the city on the Waal river to sing and drink together, while flags were waving and cannons were even fired in the area.

The reason for all this celebration was the establishment of a Catholic university – the first one in the Netherlands. After Leiden, Groningen, Utrecht, and Amsterdam (twice), the country’s sixth university opened its doors in Nijmegen.

For years, there was much debate – for example about where the new university was to be located. Scraping together a start-up capital also took a lot of effort. Money raised during collections among Catholics finally made the foundation possible. Crowdfunding avant la lettre.

Emancipation

As university historian Jan Brabers writes in Een kleine geschiedenis van de Radboud Universiteit (A Short History of Radboud University), the idea of triumph was fueled by a collective sense of subservience among Catholics. Hard facts also pointed to Catholics as second-class citizens: they were much less likely to become doctors or lawyers, partly due to discrimination.

At the same time, other motives also played a role: some Catholics saw the establishment of a Catholic university as a means of halting the rising number of mixed marriages. After all, what better place than a Catholic university for handsome, young boys and girls to find their Catholic life partner?

The establishment of the university was the crowning achievement of Catholic emancipation. A victory of sorts, then, even if played out on completely different terrain than a football pitch.

Power relationship severed

One hundred years after its foundation, the Catholic faith has been pushed into the background on the Nijmegen campus. Students and staff members now come from all walks of life and adhere to many different faiths, or to none at all. The University Chaplaincy on Erasmuslaan still stands proud and tall, but students with no interest in religion are unlikely to set foot in it in the course of their studies.

And yet, the announcement in October 2020 that the Dutch bishops had suddenly decided to rescind the university’s Catholic predicate still made the national news. The university, whose original mission was to propel Catholics up the social and public ladder, lost a small piece of its soul overnight.

Although the Dutch bishops got a slap on the wrist from the Vatican – the Pope still sees Radboud University as a Catholic institution – the formal power relationship between the diocese and the university had really been cut. The bishops no longer have a say in the appointment of university supervisors.

Demerger

The actual moment of the split was salient, and for some people definitely a little painful, so close to the university’s centenary. Moreover, it was not the only major event in recent university history.

Indeed, the rift with the bishops resulted from the decision of the university and the hospital to go their separate ways – under two separate foundations. Because of this ‘administrative demerger’, each institution now has its own supervisors, instead of being watched over by a single guardian, like siblings.

Future vision

And so there the university stands, on the eve of its centenary, on its own. Scratching itself behind the ears, it wonders: who am I really?

‘This is a perfect opportunity to reflect on it for a moment,’ says Walter Breukers, who lectures at the Radboud Honours Academy and forms one half of a duo with his old student friend Jaap Godrie. The two are not easy to pigeonhole. They write books, produce paintings, and help organisations to ‘break through set thinking patterns’. Breukers trained as a philosopher and biomedical scientist, Godrie as a historian and artist.

In the run-up to their Alma Mater’s centenary, they applied for a grant from the Reinier Post Foundation to outline a future vision for Radboud University. What makes Radboud University what it is? That is the question they wanted to answer in their book. To this end, they spoke with dozens of students and staff members.

Remarkably quiet

In these conversations, one thing stood out. ‘A centenary is a time for looking back and looking forward,’ Godrie explains. ‘Much has been said and written about the history of Radboud University, but when we asked people about the future, they remained remarkably silent.’

But a university needs a vision of the future. Something to aspire to, the two say. Breukers: ‘The university’s foundation was born out of this kind of dream. That dream made it possible to take risks and show courage. You need a vision of the future to inspire extraordinary acts.’

‘It’s useful for the university to consider how it wants to engage with society’

The current times, according to Breukers and Godrie, once again cry out for courage – and a leap of faith. After all, we live in a time when one crisis succeeds another. ‘Society is changing at lightning speed,’ says Godrie. ‘It’s useful for the university to consider how it wants to engage with this process. Who am I and what can I do? Reflecting on such matters is in Radboud University’s DNA.’

Stewardship

The university has worked on these questions for the past 18 months in what is known as dialogue sessions, as part of an identity process. Staff members, students, and other stakeholders were invited to talk with each other about the university’s identity and uniqueness. With the input from these sessions, the Executive Board plans to present a story about the university’s identity and future shortly.

‘One hundred years ago, we were created by the St Radboud Foundation with a special mission: to emancipate the Catholic population,’ says President of the Executive Board Daniël Wigboldus. ‘To me, that also means thinking now about what our mission is today. That’s how we came up with our current mission: to contribute to a healthy, free world with equal opportunities for all.’

‘As stewards, it’s our responsibility to leave the world in a better state than we found it’

This is not just a slogan that looks good for the PR department. Wigboldus: ‘It is grounded in the idea that the world doesn’t belong to us, but that we are responsible for it. Catholics have a good word for it: stewardship. As stewards, it’s our responsibility to leave the world in a better state than we found it.’

‘You have a part to play’

Clearly, this mission will have a prominent place in Radboud University’s new story for the future. Moreover, the university has already anticipated this in recent years by strongly highlighting its own sustainability ideals.

Eye-catching advertisements appeared in newspapers and on social media, and there were even ads on national TV and in cinemas. Viewers were confronted with turtles entangled in nets, a burning globe, and posters of child labour, invariably ending with the slogan ‘You have a part to play!’ and the Radboud University logo.

The response to these advertisements was not unequivocally positive. Some critics wondered out loud whether it was the role of a university to play at saving the world. ‘Since when is a university an influencer who shames you for buying things?’ journalist Enith Vlooswijk wondered in De Volkskrant. She believes that this is bad for the independent image of an academic institution.

‘Since when is a university an influencer who shames you for buying things?’

Wigboldus knows this tension all too well. ‘Don’t get me wrong. Academic freedom is our number one priority. Researchers can and must follow their own curiosity. This is crucial. But the research they conduct and the teaching they offer are intended to make the world a better place. That’s something we make explicit. Moreover, selecting a profile for a University acts as a guide in making future decisions.’

Making sacrifices

Radboud University’s focus on health in its mission is easy to explain, say Breukers and Godrie. The term that often recurs in their book is ‘the whole’. The English word health originally also means whole, Godrie points out. Breukers: ‘It’s typical of the Catholic perspective on science to try and see the whole within all disciplines. Not splintering, but rather trying to see the link between disciplines.’

Young doctors at Radboud university medical center are particularly fanatical about this, the authors noticed. Every day, these doctors are confronted with patients’ health problems that are the result of stress, poverty, poor diet, and not enough exercise. Breukers: ‘They prescribe drugs, but can’t solve the underlying problem, because the underlying problem is in society. That’s why doctors are searching for a broader perspective on health.’

Catholic character

This seems to stem partly from Catholicism, argue Breukers and Godrie. ‘The idea that there’s something that transcends the individual, and the willingness to make sacrifices in its name, to do or forego something for it, that is something that is woven into the history of Radboud University.’ They point to the university’s foundation, made possible with Catholic money, but also, for example, to the acts of resistance by Professor of Philosophy Titus Brandsma during the Second World War, which ultimately cost him his life.

Jurijn Timon de Vos, a PhD candidate conducting historical research on the university’s Catholic identity, also sees bridges being built between Catholic tradition and today’s sustainability ambitions. ‘You can see Catholic emancipation as adding something extra to society. Previously, this took the shape of training Catholic doctors and lawyers. Now it takes the shape of a concern for Divine creation – whether you call it sustainability or stewardship.’

De Vos points to Laudato Si, a 2015 encyclical, in which Pope Francis advocates for treating the Earth and the poor well. A new Radboud University institute that brings together researchers and clergy to reflect on sustainability, has been named after this Papal publication.

Business Administration

Then again, you don’t have to stick a Catholic signature on everything the university does, says De Vos. ‘Clearly, the university’s mission and the accompanying terminology are interchangeable.’ He means that even at the university, they know about business administration – and how to market their institution.

‘At no point is Catholicism traded for sustainability’

What matters to him, though, is that sustainability and Catholicism need not get in each other’s way. On the contrary, they may even reinforce one another. De Vos suspects that this is what the university administration is aiming for. ‘If you look carefully, you see that at no point is Catholicism traded for sustainability. As the university puts it, it is simply reshaping its Catholic-inspired, emancipatory character, as it has always done. All this may not be that earth-shattering, but it’s quite a Catholic thing to do: create a contemporary emphasis from tradition.’

From a pulpit

And it will always continue to do so, if it is up to Godrie and Breukers. In fact, as far as they are concerned, the university could take things a step further still. ‘Precisely because of this university’s DNA, the coming decades could well be a perfect fit for Radboud University,’ says Godrie. ‘Given its character, Radboud University can be an inspiring example for other universities.’

This requires some explanation. Breukers: ‘Over the past 40 years, society has become highly individualised. Individual interest has taken precedence over the collective.’ One of the nefarious effects of this development is hypercompetition – also between universities. ‘That’s why Radboud University included an Olympic podium in its logo for the new administration building.’ Radboud University had to go with the neoliberal flow. ‘But that doesn’t suit it, traditionally. It’s better to leave things like this to Erasmus University.’

Breukers and Godrie see that there is once again a need for an inspiring vision of the future. Society as a collective wants to once again go somewhere. And it just so happens that Radboud University feels extremely comfortable at the pulpit, calling for the preservation of the planet. ‘That is where it feels comfortable.’

Cooperation

But the university doesn’t just want to preach, it also wants to act. Since we cannot save the climate or eliminate social inequality on our own, we would be well-advised to aim for cooperation rather than competition. Radboud University is ahead of its time in this respect, argue Breukers and Godrie. ‘All kinds of qualities that Radboud University attributes to itself – informality, modesty, friendliness, collegiality – may be labelled soft in the west of the country, but they are crucial if you want to work together.’

You could almost compare it to a game of football, where the best team isn’t always made up of the 11 best individual players. It’s also about whether teammates can bring out the best in each other. But we should not take the analogy much further – after all, something far more important than a championship title is at stake in the competition played by Radboud University; and you know it: that healthy, free world with equal opportunities for all.