-

Illustratie: Ivana Smudja

Illustratie: Ivana Smudja

From slut-shaming to sexist speeches – student associations regularly appear in the news due to sexism and transgressive behaviour. Rowing association Phocas and student organisation Gelijkspel tackle the problem at its root.

What do you do when your rowing coach makes flirtatious remarks that make you uncomfortable? Or when you want to kiss your Tinder date, but you’re not sure whether the feeling is mutual? These were the kinds of questions put to 250 first-year students during the introductory weekend of the Phocas rowing association. The students were invited to attend a workshop on sexual conduct, a new component of the introduction programme.

New Vox

This article can be found in the new Vox magazine, a special on transgressive behaviour. You can find the magazine in the stands around the campus, or you can read it online.

‘We want students to be clear from the start on how we treat each other at this association,’ says Iris van Heerwaarden. As commissioner for internal affairs, she was the one who put the theme on the agenda last academic year. She was inspired by the Rutgers ‘Are you OK?’ campaign, intended to prevent sexually transgressive behaviour. ‘This campaign focuses among other things on student associations, and one of their tips was: talk to your members. So that’s what we did.’

Sexy consent

Over the past academic year, Phocas has devoted more attention to sex education. This was done as part of a wider initiative around social safety, explains Van Heerwaarden. In the first half of 2022, the rowing association highlighted a different social safety theme every month, from exam stress to body image. April’s theme, ‘spring fever’, paved the way for conversations around sexual

conduct.

The programme included, among other things, a sexy consent workshop, with a GGD (Municipal Health Centre) nurse offering concrete tools for communicating about sex. How do you actually ask what your partner wants? And how do you set boundaries? These are important topics, says Van Heerwaarden, which are never covered in sex education at school.

Van Heerwaarden took the initiative of contacting the GGD with her idea for the workshop, which ended up attracting approximately 20 students. A successful experiment, she says. ‘It was a great collaboration, especially because the workshop took such a positive angle. Instead of focusing on everything that could go wrong, it centred on what positive sexual experiences can look like. This really appealed to the students. Some of the participants said afterwards that they thought this kind of workshop should be compulsory for everyone.’

Reason enough to take it one step further during Orientation Week, thought Van Heerwaarden. She sought the help of Gelijkspel, a student organisation that aims to improve sexual culture among students. To do so, Gelijkspel frequently organises workshops for larger groups of students. According to co-founder Giulia Hietink, this is very much needed, as there is too little dialogue around sexual conduct.

‘We want students to be clear from the start on how we treat each other at this association’

This is a taboo that Gelijkspel hopes to break through with accessible, interactive workshops. Together with organisations like Rutgers and the Centrum Seksueel Geweld (Sexual Assault Center), they developed a programme tailored to student life. Hietink: ‘We presented students with case studies they could identify with. This helped bring on a dialogue, for example on how to set boundaries, the pressure of having to have sex with lots of people, or the pressure of not being able to.’

According to Hietink, this dialogue is most effective when the conversation is playful and light, without losing its serious undertone. ‘This is why we use metaphors. We talk about the sexual game, the players, and the rules of the game. And we focus on the positive: what kind of culture do we want to create?’ According to Hietink, this light approach makes it easier for students to join in the conversation, and also to take a critical look at themselves.

Safety net

Their approach works. In four years’ time, Gelijkspel has grown from an idea casually put forward at a party to a national initiative. To meet the growing demand, the organisation has launched ambassador teams in Utrecht, Amsterdam, Leiden, and Rotterdam. Similar teams are currently also being put together in four other cities, including Nijmegen. Last summer, the teams offered workshops at more than 25 student organisations and orientation weeks.

‘We talk about the sexual game, the players, and the rules of the game’

Van Heerwaarden is already talking to Gelijkspel about establishing a Nijmegen branch. She hopes that more associations will devote attention to sex education. The first signs are positive: the news of her collaboration with the GGD has spread like wildfire. ‘I was approached by rowing associations from around the country, asking me for tips.’

Within Phocas, Van Heerwaarden is already noticing a difference. ‘There is less of a taboo around these topics. People are starting to catch on to the fact that they won’t be laughed at, and that they can trust each other.’ Here and there, some difficult stories have come to light, and more requests have come in for interviews with the Phocas confidential advisor. ‘This can be confrontational, but in a way, it’s also good that people are daring to come forward and share their stories. It also shows that there’s a safety net to catch them.’

Better protection for victims: the new moral law

Sexual consent might be high on the Lucy’s law agenda of Phocas and Gelijkspel, but it is not yet a priority in moral legislation. From a legal perspective, rape is about coercion, explains Groningen Professor of Criminal Law Kai Lindenberg. According to the law, you can only speak of rape if the perpetrator uses physical violence, threat, or psychological pressure to stop the victim from resisting. Lindenberg: ‘If you say no, and the other person proceeds regardless, that doesn’t necessarily count as rape under the current legislation.’

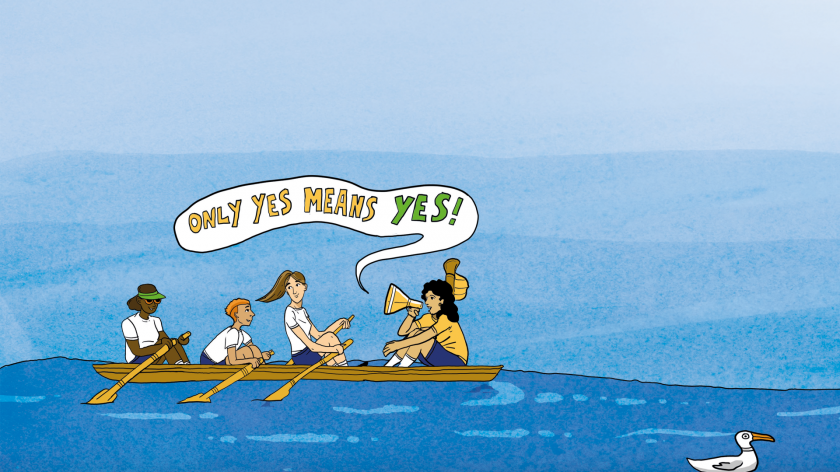

In Spain, such rules are now a thing of the past. Last summer, the Spanish parliament ratified a law stating that sex requires explicit consent. This ‘Only yes means yes’ law ensures that rape is punishable even if the victim doesn’t resist. This change could be very significant, especially for victims who freeze, and cannot resist. Incidentally, the ‘yes’ need not be explicit – according to the law, consent may also consist of actions that clearly indicate what a person wants.

In the Netherlands too, a proposal has been made for a new moral law. However, this is not an ‘Only yes means yes’ law, says Lindenberg. ‘The proposed law doesn’t state that you need explicit consent. It’s actually the other way around: you’re only considered to have crossed a boundary if you knew that the other person didn’t want it, or had serious reasons to suspect this.’

The question is: Doesn’t it ultimately boil down to the same thing? If you don’t get explicit permission, surely that’s enough reason to suspect that the other person doesn’t consent? Lindenberg: ‘Not necessarily. The assumption in the proposed law is that you have to watch out for signs of unwillingness. It’s only when the balance of power is clearly off from the start, for example if there’s a significant age difference, that the initiator should look for signs of consent. In such cases, the proposed law does approximate an “Only yes is yes” system.’

Lindenberg thinks that the new law does provide much better protection for victims. And yet, he also wonders whether it will in practice lead to many more convictions. ‘It’s still one person’s word against another’s. Without additional evidence, it’s difficult to prove that there was no consent.’ The penalty for rape under the new law is four to twelve years, depending on circumstances.

The new law, which has been years in the making, will enter into force in 2024, at the earliest. Lindenberg understands that. ‘It’s better to take a bit longer and write a good law, than to rush and but a law out into the world that will lead to confusion for many years to come.’

Translated by Radboud in’to Languages.