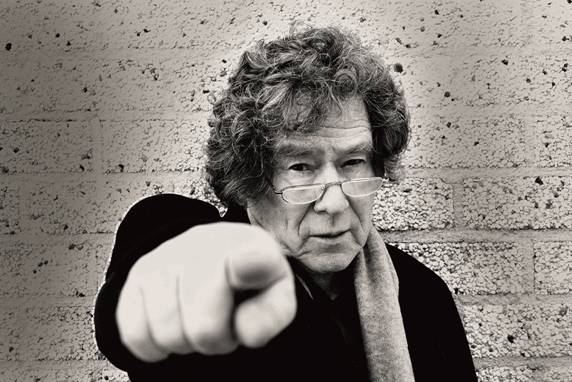

Summer interview (4): Leon Wecke

-

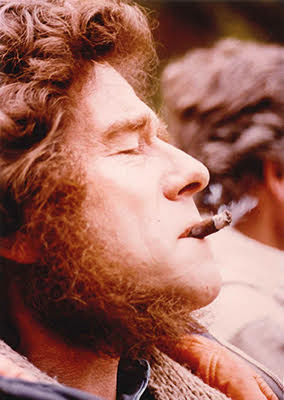

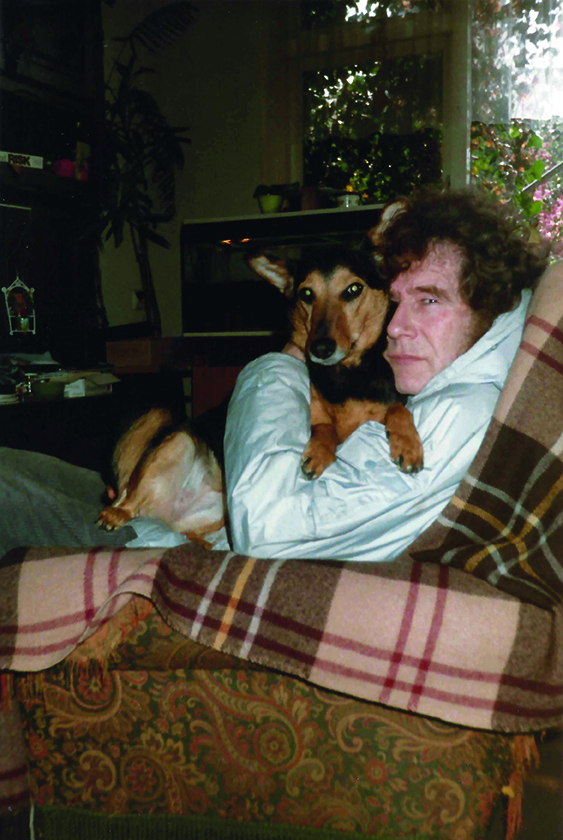

Photos: Archive Leon Wecke en CICAM

Photos: Archive Leon Wecke en CICAM

How contrary can a person be? With his unconventional lectures on conflict and images of the enemy, Leon Wecke, who passed away last year at the age of 83, remained faithful to the University almost until his last breath. A profile of a man who will be remembered by many. ‘Unconventional thinkers like Leon are unfortunately becoming increasingly rare.’

On 19 May 2015 Leon Wecke was still teaching the course he himself had introduced to Nijmegen fifty years earlier: Legitimation of Security Policy. In short: why are we so afraid of bombings when we are much more likely to die in a traffic accident or in hospital? He stimulated his students with these unconventional ideas up to three weeks before he passed away, on 13 June 2015, aged 83 and the University’s oldest lecturer by far.

Vox spoke to seven people from Wecke’s circle to flesh out the man and his intellectual legacy, and in all seven interviews laughter constantly bubbled up to the surface, no matter how much they missed him. His intense passion for work was the subject of many anecdotes. For instance for his wife, Janny Wecke, who remembers Leon’s many hospital visits: he was hospitalized at least seven times in the last twenty years, all due to his increasingly fragile heart. ‘On visits to the cardiologist he always brought along his departmental reports. Half the conversation was about that; only then would it shift to his heart.’ According to Janny Wecke, Leon preferred to be hospitalized at Christmas time. ‘He couldn’t go to work then anyway. Instead he would lecture surgical assistants on polemology.’

Work, work, and more work. Jan ter Laak, who joined the Study Centre for Peace Issues (now CICAM) as a volunteer 25 years ago, tells us an anecdote about Leon’s holidays – they were non-existent. ‘Holiday? There’s nothing to do on holiday!’ Leon used to say about the free weeks that offer such pleasant distractions to regular mortals. When Wecke did finally decide to go away, to Cattolica on the Roman Coast in 1990,the fun was of short duration: the First Gulf War broke out on 2 August. ‘He ended up spending all his days analysing, making phone calls and writing,’ says Ter Laak. His wife Janny was there, and she can laugh about it. That was Leon. ‘He barely made it to our son’s birth.’ In 2006 they took the same trip again, to celebrate their 35th anniversary, together with their children and grandchildren. ‘That time everything went well, and luckily no war broke out.’

Action Group RaRa

What drove this man to constantly want to share his vision on war and peace? To not want to miss a single development? To continue to prepare lectures with one foot in the grave? His hunger for news was legendary. Ben Schennink tells us about the television Wecke has installed in his car back in the 1970s, so that he didn’t miss the news on his way to work or to a lecture. ‘Whenever something happened, Wecke immediately called to give us a preliminary analysis of the news. We often first heard about important events from Leon,’ says Schennink, who arrived in Nijmegen in 1969 to strengthen the academic staff of the recently launched Study Centre.

Wecke was driven by a mission to enrich the world with his vision on every new war that threatened to break out. The insights into polemology acquired in Paris in the late 1950s formed the foundation for his (often sharp) commentary on every new conflict – and the public response it engendered. For example in 1991, when the country was shocked by a bomb exploding at the residence of Minister Aad Kosto (Asylum Policy). The attack was claimed by the Action Group RaRa, who for a few years advocated, in a rather un-Dutch aggressive way, the rights of illegal asylum-seekers.

A ‘terror group’ according to the community at large, but not to Wecke, who once again took an alternative stance: ‘Didn’t they always politely warn everyone before the explosion? Although they say that Kosto’s cat may indeed at some point have been in danger.’ Since a couple of RaRa supporters were following Wecke’s lectures, and Wecke himself was working on a publication about the group, the secret services conducted a night raid on Wecke’s office at the University, looking for the bombers’ names. Names that Wecke did not know. Wecke enjoyed telling this story: it strengthened his reputation as an unconventional polemologist.

Unconventionality with a serious undertone, emphasizes Ben Schennink. ‘He fought against the legitimation of conflicts that cannot be legitimised.’ ‘He invited people to look at conflicts from all perspectives,’ says Maarten Cras, who was introduced to Wecke in the early 1990s when he followed courses at the Study Centre as a student. ‘He always said: ‘William of Orange was the greatest terrorist the Netherlands has ever known.’ It’s all a question of definition: a freedom fighter to one is a terrorist to the other.’

Rebellious

Where did Wecke get his unconventional ideas about war and peace? What drove him to testify to this day in day out for half a century? Ben Schennink reflects on Wecke’s youth in Arnhem, on the frontline in 1944. While citizens fled to the shelters, twelve-year old Wecke went out to witness the Battle of Arnhem with his own eyes. An even more important incident according to Schennink occurred in the following months, as the Wecke family fled and found shelter in the Achterhoek, near a farmer who was a Dutch Nazi (NSB), but nevertheless helped an English pilot who was shot down. The farmer was later tried and exonerated by Wecke’s father – active during the war in the Red Cross. What is right? What is wrong? ‘This plea of his father’s was a real eye-opener for Leon,’ says Schennink.

During his own military service, Wecke discovered that every conflict situation has a false bottom. In 1953 he carried sand bags during the floods in Zeeland. Later, he refused to go on refresher exercise and became one of the first atomic conscientious objectors of the Netherlands. Autonomy was more important than blindly following authorities, as Leon learned during the war. ‘This ambiguity towards authority is something that Leon carried with him for the rest of his life,’says Schennink. Maarten Cras remembers an important episode from Leon’s military service, when he was locked up for ignoring an order to remain in the camp, even though the division had been promised a free weekend. ‘In Leon’s eyes this was unjust. His twin brother, a corporal, went to visit him in prison.’ This brother – a few minutes older than Leon – has played an important role in his life, says Schennink. ‘The elder of a pair of twins is often very law-abiding, so the second one has to do something different to attract attention. Leon had a tendency to rebel from an early age,’ analyses Schennink.

‘He absolutely hated authority,’ says Jan ter Laak. ‘At the Institute, the conscientious objectors who came and went had as much say as the permanent staff.’ Helma Jacobs, Wecke’s secretary since the 1980s, praises his leadership style, armed with generosity and humour, and averse to performance. ‘Other bosses liked to show off that they had studied, but not Leon.’ Maarten Cras mentions Leon’s dislike of academic bureaucracy. ‘He believed that there were too many rules.’ Leon was dedicated to his students, not to the university authorities.

Performer

The fact that Leon favoured the media above the scientific podiums was part of his unconventional attitude, says Bert Bomert – Director of the Institute following Wecke’s ‘retirement’. ‘He considered research to be a party trick: you had to write the right publications with the right hypotheses, which according to him nobody ever read.’ In the media and in debates he could express alternative opinions. ‘Even though he did it for fun, his unconventional approach often did lead to better insights.’

Leon was a vegetarian who hated animal slaughter, which resulted in a rabbit plague

The performer in Leon Wecke also craved attention. In his younger years he had wanted to go to drama school. ‘Not follow the masses, but get on stage and let the message of protest be heard,’ that is how Maarten Cras summarizes Leon’s calling. He never refused a request for an explanation or a lecture. For years, twice a week he recorded a column for Gelderland Broadcasting, and he was home columnist for Radboud Reflects. Until his heart forced him to say ‘no’ more often. ‘He really struggled with this,’ says Cras. Jan ter Laak knows that Leon was afraid that if he said ‘no’, people would stop asking him. ‘Leon couldn’t do without company, he was addicted to people.’ He so much wanted to share his vision with the public, says his wife Janny. Helma Jacobs notes that Leon remained unconventional until the very end. He ‘was hurt’ when invitations to perform became less frequent. But all her advice – Work less! Eat better! Exercise more! – was lost on Leon. ‘It was nobody else’s business.’

In the last fifteen years, his wife Janny drove Leon to work; he didn’t want to drive anymore himself. ‘Leon was afraid that there would be no one to take over his work, so he had to be at his post.’ Nor did he rest at home. ‘In the evenings and the weekends he would often sit in his study.’ And yet he was not good at being alone: ‘Even when he worked, he wanted me to stay at home.’ ‘He was not the kind who wanted to do things together, just the two of us,’ says Janny. Work and children came first, followed far behind by animals, like the birds he studied in the Ooij Polder, or the rabbits in the garden. Leon was a vegetarian who hated animal slaughter, which resulted in a rabbit plague. Which in turn led to a fight with the neighbours, and uncontrolled hordes of rabbits being released by Leon near Malden.

Incredibly relevant

How time-proof is Leon Wecke’s intellectual legacy? He did not leave any books, not even a PhD. This was partially strategy, says Ben Schennink: ‘If we had taken the time to write PhDs, the Institute would not have survived.’ We made a name for ourselves through media attention, fund raising, and securing research assignments, he explains. ‘We were very good at it, and that’s what saved the Institute.’

Jan ter Laak knows that Leon began working on at least three PhDs, one of which he very nearly finished. ‘The manuscript is still somewhere in a drawer. He also had enough articles that only required a staple, but he never got around to it.’ Approximately ten years ago, Leon’s employees reserved a room for him in the Erasmus Building for three months: ‘Now get to work on your PhD!’ Ter Laak: ‘He was back at the Institute within ten days; ultimately he wasn’t interested in a PhD.’ Janny Wecke: ‘He hated sitting alone in his room. He wasted away when he didn’t have an appointment.’

Maarten Cras does not regret this missing PhD. ‘Leon has left enough of a legacy: an incredible collection of lectures, articles and columns. Once all this material has been put in order, it will form a beautiful legacy.’ Bert Bomert adds: ‘Generations of students were raised on Leon’s intellectual legacy. When he died we got messages from people who had studied with him twenty years ago: ‘What a loss!’ This is also a way of leaving a legacy: all these students will carry his vision forward for many years to come.’

‘He would turn the world upside down’

This is certainly true of Laura van den Vrijhoef, Master’s student in Political Science, who followed a Minor with Leon in 2014, his last year. Once she became used to ‘his unique style of teaching and somewhat old-fashioned language use’, she enjoyed ‘fantastic lectures’: ‘He would subtly lead us towards a new way of looking at things.’ What do we miss now that he is no longer among us? Ben Schennink mentions the trips they used to take together, the last one to the German military war cemetery in IJsselsteijn, Limburg, where Leon stumbled on the graves of two Weckes unknown to him. Leon’s grandfather was German, and these two new-found members of the Wecke family touched him, says Schennink. ‘For a moment it turned his world upside down: Nothing can be taken for granted, you always have to remain open towards people, as he showed in his attitude towards the Russians in the Institute’s early days.’

Jan ter Laak misses Leon as ‘the grown-up child that he always remained.’ So playful! For instance at the annual party at the Wecke’s home – attended by everyone, from military personnel from the Defence Academy, where Leon taught, to conscientious objectors – and where the traditional roulette game was once disturbed by three police agents barging in. ‘Leon had organised this himself; the costumes came from the drama school.’ Bert Bomert remembers the man ‘with whom it was impossible to fight’, ‘who took your arm when it was needed’ and who was as much part of the Institute as the furniture. ‘He was always there, the man whose door was always open for an exchange of ideas. This is what we have lost.’

‘I miss working days that started with the appearance of a cheerfully muttering man’, says Maarten Cras. ‘It usually turned out that Leon had heard something on the news, which, being him, he simply had to comment on.’ Helma Jacobs misses the ‘scatterbrain’ whose secretary she became 37 years ago. ‘The day would only really start once I had had a chat with Leo. Luckily he was always there. Even when his health was failing, he still considered the Institute more important than the hospital. We even had to take exam papers to him in hospital because he wanted to grade them himself.’

The woman whom you would expect to miss him most, Janny Wecke, finds it a difficult question. Of course she misses the ‘nice boy’ she met 63 years ago. ‘But you know what’s strange: in some ways I don’t miss him. I still talk to him nearly every day. When I see something on TV, I sometimes say: ‘Did you hear that? That’s what you always used to say!’’

The final word goes to the student, just as Leon would have wanted it: ‘I think he made a lasting impression on me,’ says Laura van den Vrijhoef. ‘His style may have been old-fashioned, but what he had to say was incredibly relevant.’