Surinamese slave registries online

-

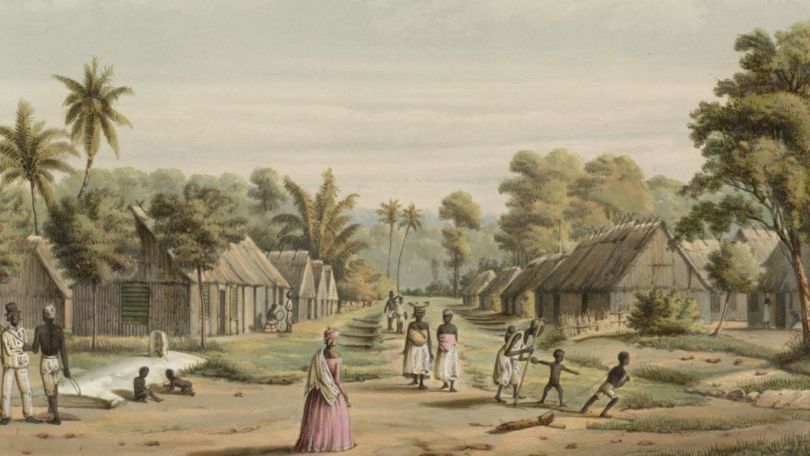

Slavenkamp in Suriname, jonkheer Jacob Eduard van Heemskerck van Beest, naar Gerard Voorduin, 1860 - 1862 (via Rijksmuseum)

Slavenkamp in Suriname, jonkheer Jacob Eduard van Heemskerck van Beest, naar Gerard Voorduin, 1860 - 1862 (via Rijksmuseum)

It will only be official on 1 July, during KetiKoti. But the digital Surinamese slave registries are already online. A considerable undertaking, with which historian Coen van Galen received help from hundreds of volunteers.

Actually historian Coen van Galen finds it a bit strange that no one did this work earlier.

For most Dutch people today it isn’t very complicated to trace their own family lineage: nearly all regional archives offer an online search tool through birth and marriage registries that often go back hundreds of years. But for the descendants of slaves in the former Dutch colony of Suriname, that has not been the case.

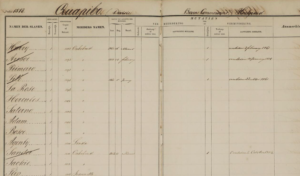

Slave registries were in fact available in the Suriname National Archive in Paramaribo – which is unique in itself: nowhere in the world has such an administration been securely kept – but they have not provided much insight. They consist of enormous tomes and you need to have a bit of luck to open them up and hit upon an ancestor.

With his Surinamese colleague Maurits Hassankhan (former minister of Foreign Affairs and researcher at the University of Suriname) Van Galen decided to digitalise the registry just a year and half ago. The searchable database will be officially launched this Sunday during KetiKoti, an annual holiday celebrating the abolition of slavery. But the database is already online on the website of the National Archive.

Crowdfunding and crowdsourcing

The assistance of all inhabitants of the Netherlands and Suriname was enlisted. In January 2017 Van Galen and Hassankhan started a crowdfunding campaign to raise twenty-five thousand euros. That amount was raised in a month – and in the end it came to forty-one thousand.

Van Galen entered the scanned pages of the registry, around seventy thousand in total, onto velehanden.nl, a crowdsourcing website that showcases the collections of archives and museums. ‘The volunteers got to work, typing in the information from the registry. The name of the slave, their sex and date of birth, but also the name of the mother and his or her ‘mutation date’.’

‘I can look up my family history, I also want them to be able to’

Exactly 369 volunteers filled in one or more sheets. Some grew fanatical about it, and all had widely varying backgrounds. According to Van Galen: ‘At one of the volunteer meetings that I organised, an older man from Goeree-Overflakkee told me about his motivation: ‘I can look up my family history, I also want them to be able to,’ he said.’

Alongside making the registry publicly available, diversity has also become a goal of the project, states Van Galen. ‘I find it very important that we have generated attention to the history of slavery in this manner. Without discussion and without us-them thinking a very mixed group pored over the material and worked at it.’

After 1863

In his room in the Erasmus building Van Galen scrolls through his Excel sheets. ‘It looks business-like, doesn’t it, all this data? But there are many people behind this.’ The registries are an extraordinarily important connection to other sources. Certainly the combination of the proper name and that of the mother – ‘A slave never has a father’ – makes linking up to information from other databases possible, such as the newspaper archive Delpher.

‘Up to now the family trees of many Surinamese was a black box prior to 1863, the year of the abolition of slavery in the West,’ says Van Galen. The database is therefore very important for many families. In the meantime, for his own research Van Galen looks further. Life didn’t stop in 1863, and for that reason the next project is already underway: now the Suriname citizen registry up to 1950 – in which freed slaves were subsequently recorded – will be digitalised.

That’s when it gets really interesting: ‘Then we can research how a period of enslavement affects someone in later life as a free person. Do they have children or not, or a job. What are their expectations of life, where do they end up?’

Ruti Vorswijk schreef op 23 oktober 2018 om 02:43

Hou can I find my maroon grandfather of Surinam ? I am very intresting about

O.W. ten Hove schreef op 6 mei 2019 om 22:39

Its a shame that dor Cornelis Willem Van Galen did not react, but that is the way people who are not connected tot the Radboud knows him… so I will answer.

In the slaveregistraion you will not find Maroons for the were no slaves…