The housing market is a Greek tragedy that affects all generations

-

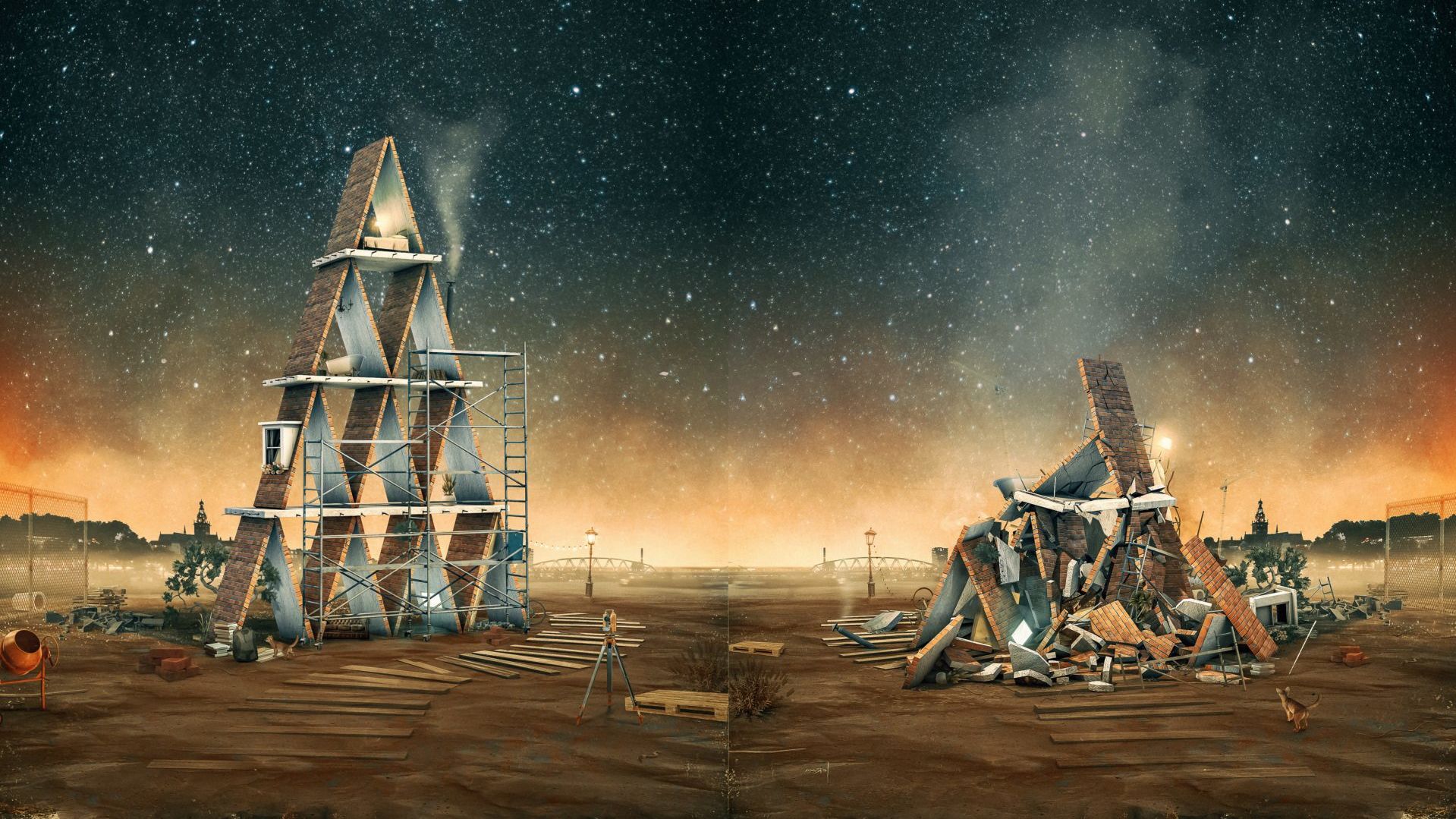

Illustratie: JeRoen Murré

Illustratie: JeRoen Murré

Students are reduced to sleeping on camping sites, and the prices of rental and owner-occupied properties are rising through the roof. A house advertised on Funda today will have a new owner within three weeks. Will the Greek tragedy that is the housing market ever end?

Last March, it happened for the first time, and estate agent Attis van der Horst remembers it well. For the very first time ever, she had clients who bid €100,000 above the asking price. ‘I’ve been assisting house buyers for fifteen years, but I’d never seen anything like it.’ These days, the asking price is not much more than an invitation to come and have a look, she sighs in her office on the Van Welderenstraat. ‘If you want to have a chance, you’ve got no choice but to overbid.’ Van der Horst’s clients increasingly resort to searching in traditionally less popular areas like Dukenburg.

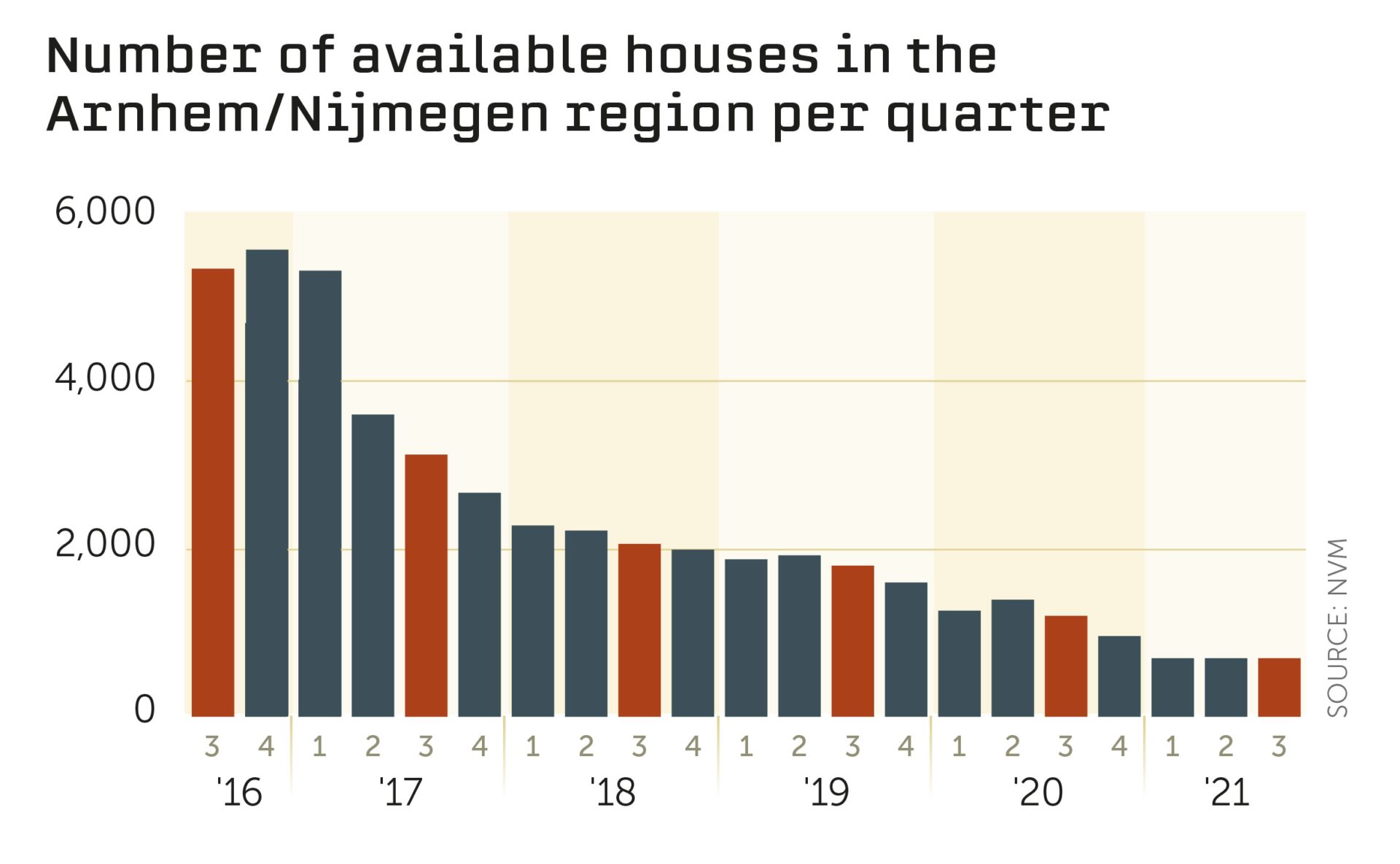

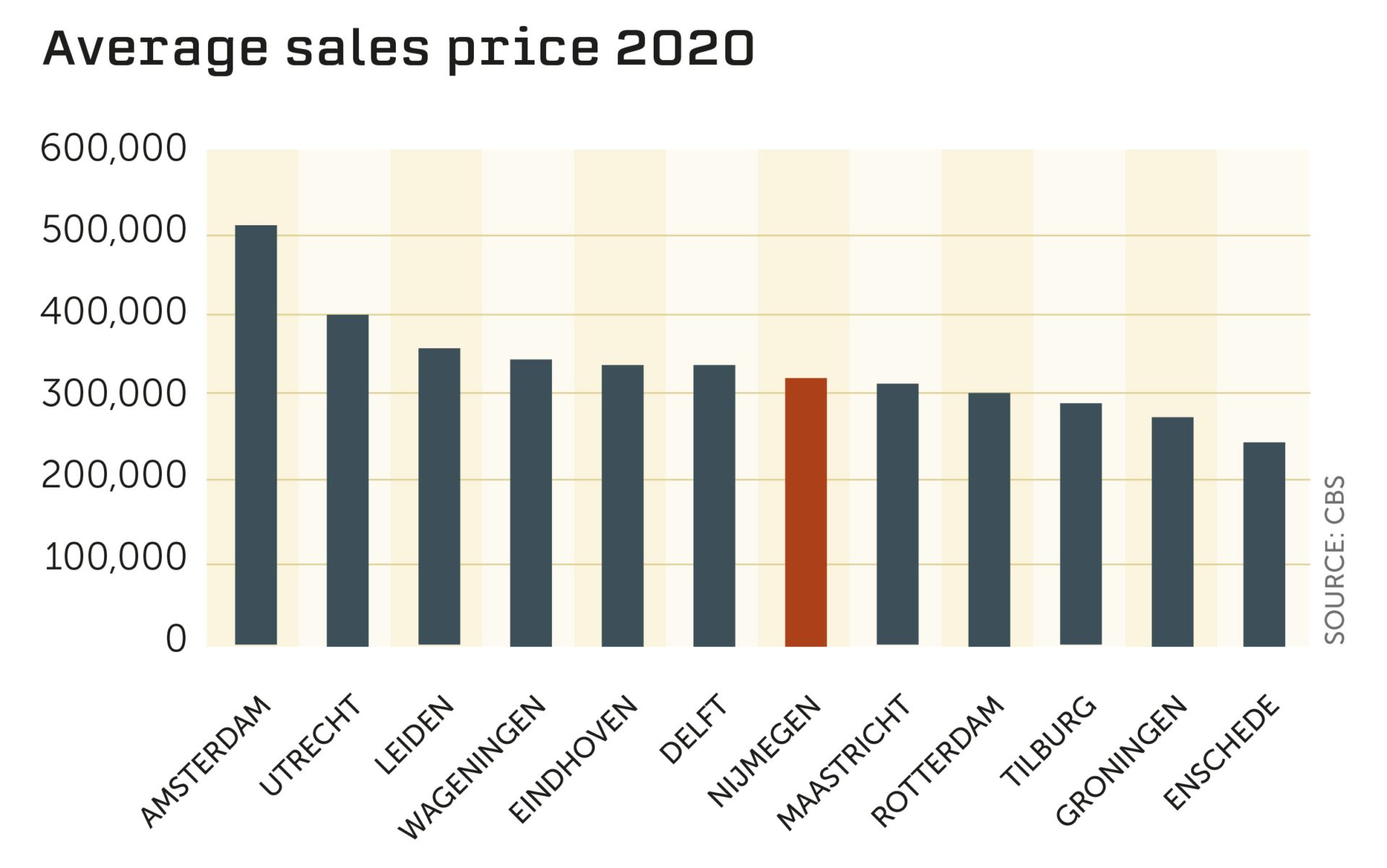

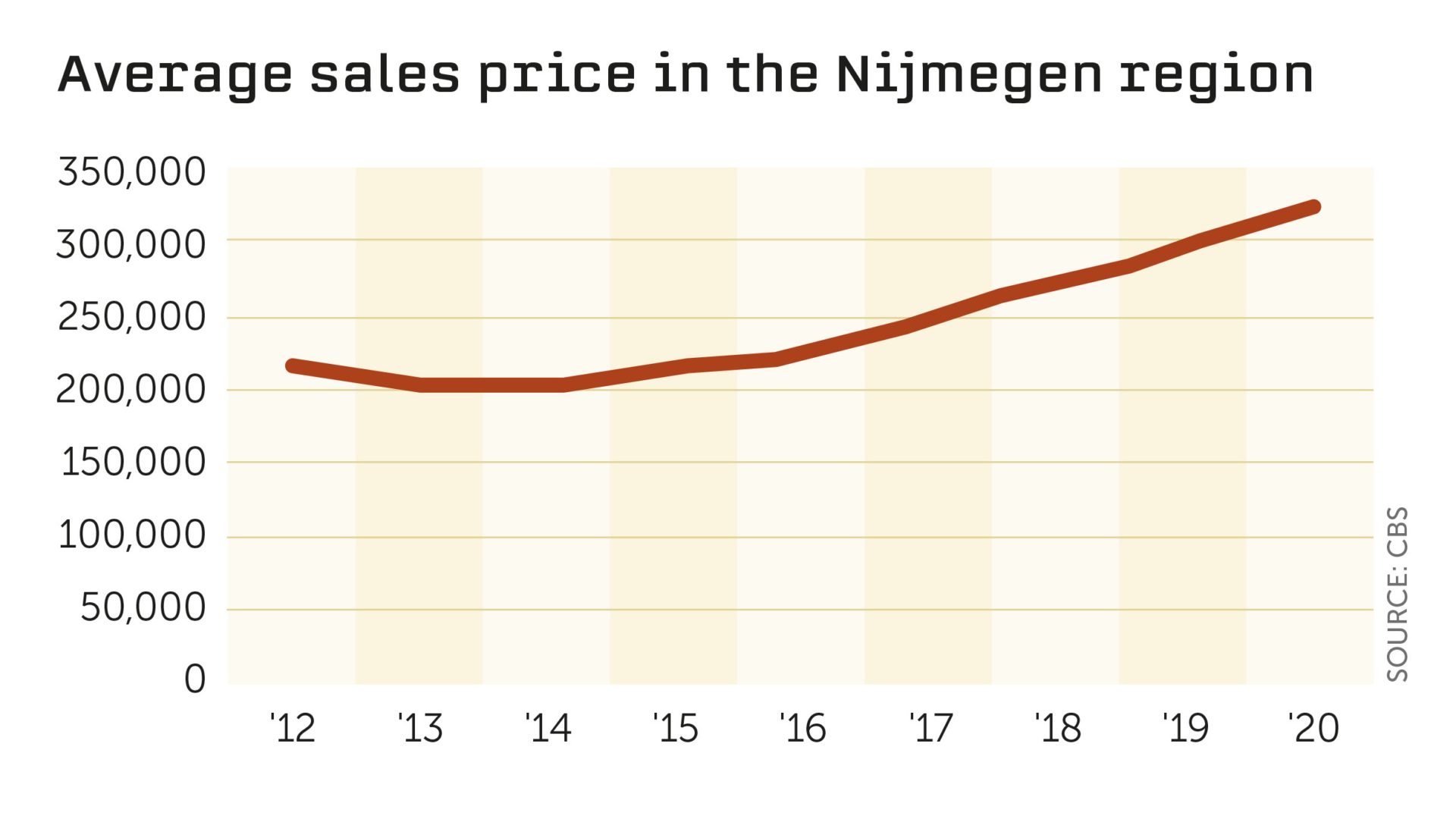

But there too, prices are rising dramatically. More than 85% of properties for sale in the Arnhem-Nijmegen region – with the exception of detached properties – are currently sold for more than the asking price, as apparent from the figures of estate agents’ association NVM. The average selling price is €383,000, nearly double what it was in 2013. That year marked the most recent low point on the housing market, which had collapsed as a result of the credit crunch. Between 2008 and 2013, houses lost on average 20% of their value. Recent university graduates and other starters on the housing market were in a luxury position in those days, remembers Van der Horst. ‘They could take their pick of houses.’

But there too, prices are rising dramatically. More than 85% of properties for sale in the Arnhem-Nijmegen region – with the exception of detached properties – are currently sold for more than the asking price, as apparent from the figures of estate agents’ association NVM. The average selling price is €383,000, nearly double what it was in 2013. That year marked the most recent low point on the housing market, which had collapsed as a result of the credit crunch. Between 2008 and 2013, houses lost on average 20% of their value. Recent university graduates and other starters on the housing market were in a luxury position in those days, remembers Van der Horst. ‘They could take their pick of houses.’

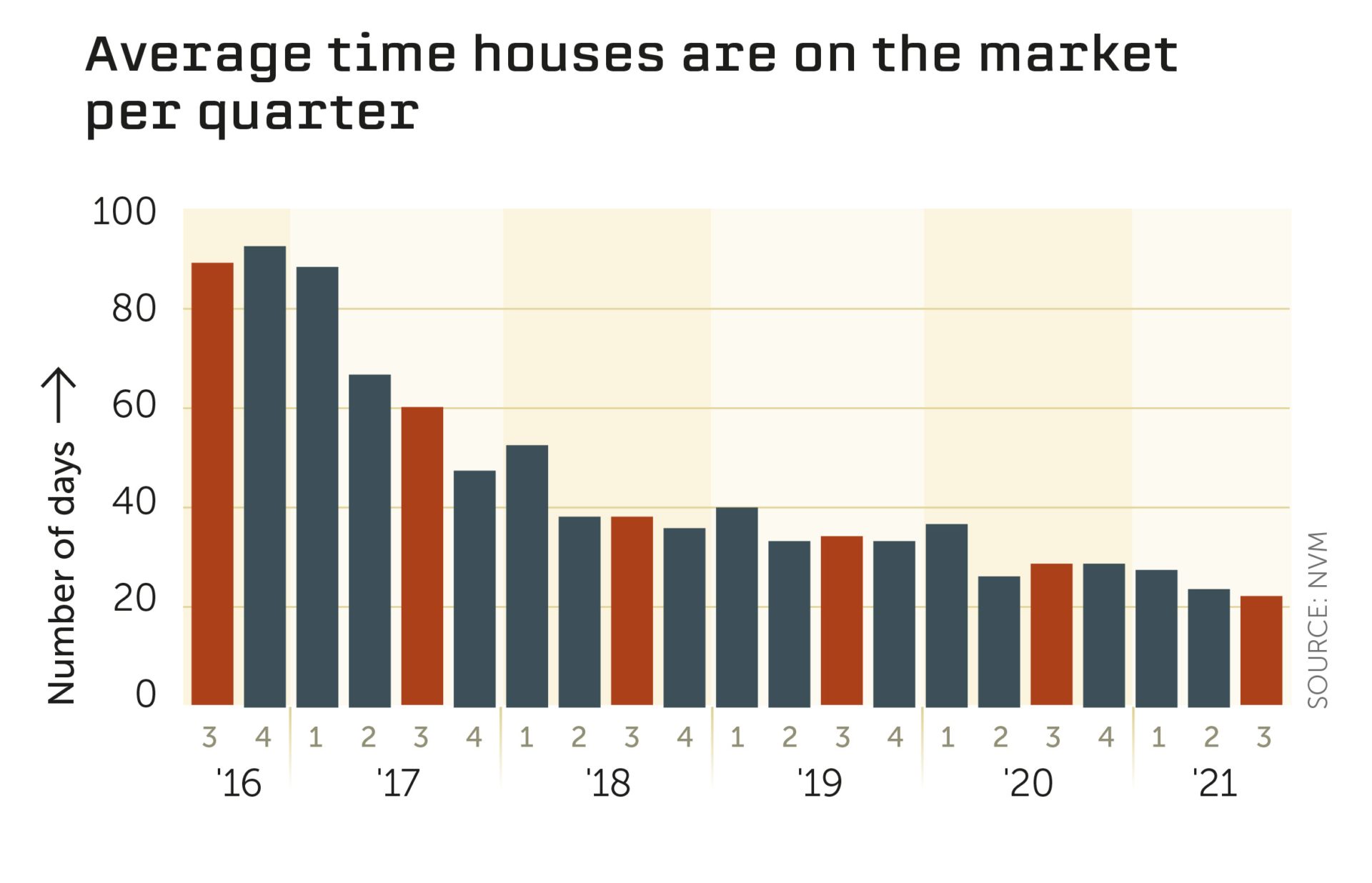

A property advertised on Funda today will be sold within three weeks

These days, the situation couldn’t be more different. A property advertised on Funda today will be sold within three weeks, says Paul de Vries, housing market researcher at the Dutch Land Registry Agency. ‘In normal market conditions it usually takes about three months.’

People looking to purchase a home are not the only ones who are stuck. To qualify for social housing in the region, you have to be registered for an average of 19 years, as apparent from the 2021 ArnhemNijmegen Housing Market Monitor – and in principle earn no more than €40,000 per year. If your income is higher, and buying a house is not an option, your only recourse is the private rental market, where offerings are limited and prices high. What about students? They are sometimes forced to seek refuge in hotels or camping sites in and around Nijmegen. Throughout the Netherlands, there is a shortage of 26,500 student rooms, as calculated recently by Kences knowledge centre.

In other words, the difficult quest for a place to rest one’s head is affecting all generations and layers of society. And unsurprisingly, the first initiative for a ‘housing protest’ in Nijmegen in decades, on 31 October, was met with a great deal of enthusiasm. The overheated housing market is like a Greek tragedy in which mere mortals find themselves the plaything of higher powers. Some parties come out as winners, at the expense of powerless victims. Saviours flying to the rescue are sometimes revealed to be Trojan horses. And ultimately, nothing short of a powerful deus ex machina can still give the story a positive twist. What persons and organisations play a role in the key drama elements?

Higher powers drive prices up

The acute shortage of homes for sale is the result of a number of factors, which individual house buyers have little influence on, explains Paul de Vries from the Land Registry Agency. It starts with the fact that many people want to relocate. ‘This desire is something that’s always present of course, but many people who owned a property put their relocation plans on hold during the financial crisis, because their house dropped in value. Now that selling is profitable once again, they can finally make a move.’

In fact, adds estate agent Van der Horst, due to the continuously rising house prices, even people with no relocation plans suddenly feel under pressure to turn the surplus value of their house into cash. ‘There’s this idea going around that you’re shooting yourself in the foot if you keep all this money invested in bricks and mortar.’

At the same time, private house buyers increasingly have to compete with investors who purchase houses only to rent them out or resell at a profit. ‘They can easily get funding thanks to the low interest rate, and they all want maximum return on their investment,’ says political economy expert Angela Wigger, who studied the housing market in Amsterdam and other places. Investors who used to put their money in companies that manufactured goods – the ‘real economy’ – now increasingly invest in property. Wigger: ‘The profit margins are high and the risks are low. Since 2013, the rental market has become more liberalised, which makes it easier to offer people temporary rental contracts.’ It also makes it easier to get rid of tenants, for example by selling the property or raising the rent in the middle of the contract period.

Winners who risk nothing

The winners of this drama are mostly those who have no trouble putting money on the table. People with a well-paid stable job who already own their own home. They can easily get a new mortgage; having perhaps already paid off part of the old one, they have a substantial surplus value in their house, and in some cases even some savings. De Vries: ‘For the same monthly payment, they can suddenly afford to live in a much larger and more expensive house.’

A house that could easily be worth twice the value, as a quick calculation shows. Imagine that in 2013, as a PhD student, you purchased a terraced house in Hazenkamp with your partner for €300,000, with a regular mortgage in those days, at 4% interest rate, with a fixed rate for 10 years. This means that, thanks to the home mortgage interest deduction, you pay approximately €600 net per month in interest. At the current 10-year interest rate (approximately 1.5%), you would have to borrow €800,000 to pay a similar amount of interest.

‘It causes a lot of stress’

‘The search for a house to buy can be quite depressing’, says Lara de Die (29), Communications officer at the Faculty of Philosophy, Theology and Religious Studies. ‘You have to call or email for a visit straight away, otherwise you’re sure to be too late. My boyfriend and I have been looking for our first home since this summer. The other day, we almost got lucky when we bid €60,000 above asking price. But in the end, someone else got in before us. Sometimes I think: If we can’t find anything with two permanent jobs, what are people who don’t have stable jobs supposed to do?

Ideally, we’d like a corner house with a long garden. We are currently renting an apartment in Hazenkamp, but this neighbourhood is beyond our budget, with an average price of €400,000. This is why we’re also looking in the villages around Nijmegen, and we recently hired a buyer’s agent. It definitely causes quite a lot of stress. But you can’t put your life on hold until the market calms down. If we find a nice home and the market collapses, we’ll just stay put and wait for the storm to pass.’

Of course, you have to find a bank willing to loan you this money. But if, in the meantime, you’ve both been promoted to assistant professor, with a monthly salary of twice €5,000 (salary scale 12.4), then a loan of €700,000 is feasible. If you also manage to sell your house for €500,000 (a conservative estimate), you can move to a house worth a million, while your interest payments will remain the same or even decrease a little.

It’s a zero-risk operation, in other words. Clearly, there are other costs involved, such as the property transfer tax, potential renovations, higher energy costs and, of course, a larger debt. The latter, in particular, could become problematic once house prices drop once again.

Newcomers are the losers

So who are the losers in this game? De Vries: ‘Those who recently appeared on the stage: young people who need a full mortgage to buy a house for €400,000.’ They cannot compete against prospective buyers who put in the entire surplus value of their previous home, their savings, or a ‘jubelton’ – see below. Their living expenses are also higher because, unlike existing home owners, they have to repay the entire mortgage amount during the mortgage term.

Even more hopeless are people who can get no or too little mortgage. For example because they are single or a freelancer, or because – like three out of five researchers at Dutch universities – they have a temporary contract. They are often reduced to searching on the private rental market, since they earn too much to qualify for social housing.

‘Houses shouldn’t be speculation objects’

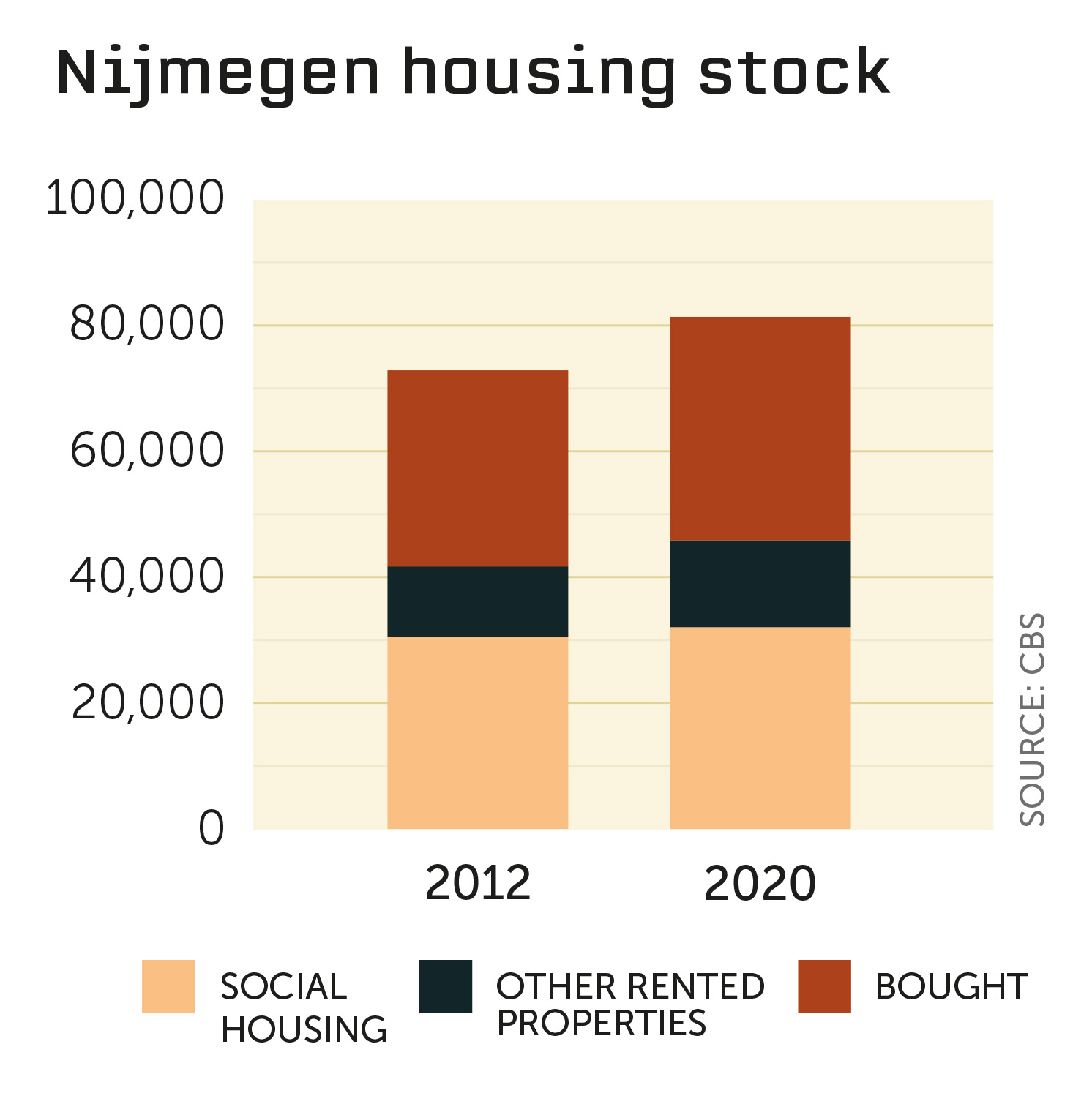

But in the private sector, offerings are limited and rents are high. Only one seventh of all housing units in Nijmegen falls within this category. According to Professor of Planning and Property Development Erwin van der Krabben, this is due to the fact that this ‘middle rental segment’ is not subsidised by the government, unlike people in social housing and home owners. ‘Both groups receive approximately €15 billion in subsidies per year, the latter via the home mortgage interest deduction.’

The result: in one ad on the Pararius rental site, someone is asking over €1000 rent for a two-room apartment of 50m2 in Bottendaal. Maximum rental period: six months. And in cities like Utrecht, prospective tenants can now even outbid each other. This makes it even harder to save money: the divide between rich and poor is increasingly becoming a divide between tenants and home owners.

Ultimately, it is students and other young people who end up paying the price. People in cheap rental houses prefer to stay put, even if their income incre ases over time. University graduates are less likely to move on, and are forced to remain in their student rooms. And this while the demand for student accommodation remains as high as ever, especially now that international students are once again finding their way to Nijmegen post COVID-19. There is no way SSH& can build enough housing units to meet this growing demand.

Saviours sometimes turn out to be Trojan horses

But wait a minute. Aren’t we building lots of new houses, in the Waalsprong and the Waalfront? Will the construction companies save the day? Yes and no. Between 2019 and 2024, Nijmegen will need to build nearly 10,000 additional housing units, according to the Housing Market Monitor. Half of these are supposed to be social housing units and houses for purchase for up to €310,000. But construction is running behind schedule – especially for cheaper houses worth up to €200,000.

‘We’re building too slowly, and in the wrong way,’ says Van der Krabben. With the rising house prices, construction companies are not always motivated to build quickly, he says, especially if they already own the site. The longer they wait, the more money they can ask for the houses they still have to build. ‘On the Metterswane location, across the street from the station, a new apartment building should have been completed a long time ago.’ What’s more, project developers prefer to build expensive single-family units rather than the cheaper apartments and single-storey houses needed by starters and seniors. And as long as older people remain in their sometimes rather large houses, turnover on the housing market is slow.

The Dutch government also behaves more like a Trojan horse than a saviour swooping in to solve its citizens’ problems, explains economist Wigger. Government measures only drive house prices up further. For example, after the credit crunch, the government lowered the property transfer tax from 6% to 2%. This is the percentage of the purchasing price you have to pay in tax when you buy a house. ‘It means that buyers now have lower costs, and they use this money to put in higher bids.’ This is especially true for starters, who currently don’t pay any property transfer tax at all.

The Dutch government also behaves more like a Trojan horse than a saviour swooping in to solve its citizens’ problems, explains economist Wigger. Government measures only drive house prices up further. For example, after the credit crunch, the government lowered the property transfer tax from 6% to 2%. This is the percentage of the purchasing price you have to pay in tax when you buy a house. ‘It means that buyers now have lower costs, and they use this money to put in higher bids.’ This is especially true for starters, who currently don’t pay any property transfer tax at all.

Young people can also afford to bid more thanks to the ‘jubelton’, a tax-free gift of €100,000 that parents can give their children. ‘For a large group of older people, this isn’t a problem. They have money left over when they relocate to a smaller house. And those who choose not to move can always raise their own mortgage based on the surplus value of their home.’

A deus ex machina to the rescue – or not

There is one thing that all experts agree on. A lot more regulation is needed to bring calm to the overheated market. If the government does its job well, it could still act as a deus ex machina and provide the necessary solution, just as in a classical play. This could already happen at municipal level, says estate agent Van der Horst. ‘Increase the municipal starters’ loan [currently €225,000, eds.] for people who have trouble getting a mortgage.’ She is also very much in favour of the Nijmegen plan for a purchase protection measure (‘zelfbewoningsplicht’, making it mandatory for house owners to live in the house themselves), to discourage investors. Wigger agrees with her fully. ‘Houses shouldn’t be speculation objects, but simply places where people live.’

Professor of Planning Van der Krabben disagrees. ‘We may regard investors as semi-criminals, but they do fulfil a need. They take one house and turn it into multiple housing units, thus increasing the total housing supply.’ He is, however, in favour of housing corporations also being allowed to build housing units with higher rental prices, and the government finally introducing some form of regulation for rental units in the private sector – similar to the points system used in the social sector. The latter is something Wigger fully agrees with. She even goes one step further: this kind of system should also be used to regulate prices on the buyers’ market.

The price of a house should be based on objective features such as living area and facilities, and not be driven by what someone is willing to ask or pay. ‘And levy a tax on the rental income of private lessors,’ she adds, ‘instead of having housing corporations pay a lessor levy as they do now.’

The first signs of an approaching shift are already apparent

We should also as quickly as possible dismantle financial incentives like the ‘jubelton’ and the home mortgage interest deduction, says Wigger. And while we’re at it, also levy a tax on the surplus value of selling a house, adds estate agent Van der Horst. ‘After all, this is money people didn’t have to lift a finger for.’

But even without measures like these, the market will ultimately calm down, says De Vries. ‘It’s a natural cycle. To starters, I want to say: don’t give up, in two years’ time, things will be better.’ Rising interest rates and an economic downturn will make people more cautious when buying a house. The first signs of an approaching shift are already apparent. The mortgage interest rate is slowly rising and the Chinese economy is weakening, partially due to the problems of property giant Evergrande. Already house prices in Amsterdam have risen more slowly in the last few quarters than prices elsewhere in the country, says De Vries.

Are we on the eve of a new housing market collapse, like the one we saw during the credit crunch? It isn’t inconceivable, according to Wigger. ‘After Denmark, the Netherlands is already the country with the highest percentage of debt.’ House owners who are forced to sell their homes – because they get divorced or lose their job – will be left with residual debts of sometimes tens of thousands of euros, while having to find a new place to live. And the Greek tragedy will start all over again with Act 1.