‘The only thing the University does for Gaza is running away from its responsibilities’

-

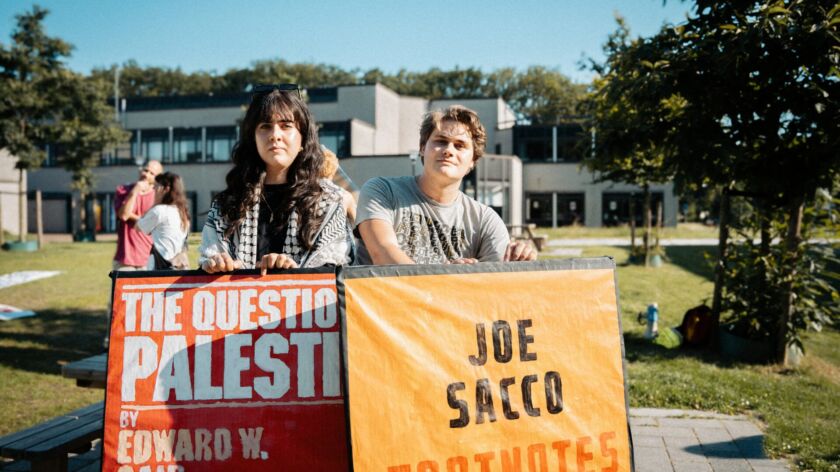

Sermin en Ties tijdens een protestactie op de campus. Foto: Johannes Fiebig

This past spring, the campus was all about the pro-Palestine protests and the call to break ties with Israeli institutions. Students Ties van den Bogaard and Sermin Sahin have been involved with the protests from day one. How do they feel looking back? ‘I think it’s almost irrelevant that things were destroyed during protests.’

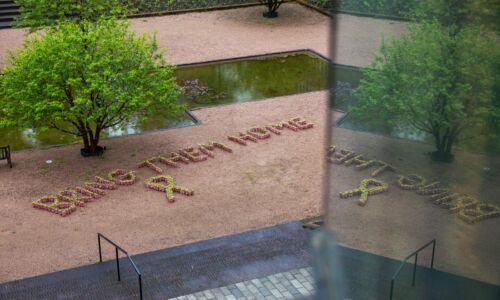

No more banners, shouting crowds, or blockades; even the tent imprints on the lawn next to the Maria Montessori building have long since disappeared. The only reminder of the encampment, which stood for roughly a month from May 13th, is the last of the children’s shoes from the art project.

Nevertheless, the genie of the pro-Palestine protests cannot be put back into its bottle at Radboud University, according to spokespersons Ties van den Bogaard (24, student of philosophy) and Sermin Sahin (23, student of healthcare psychology). ‘The campus is relatively quiet over the summer’, Van den Bogaard says. ‘We want to protest when and where we will be seen. That is why we’re considering protests during the Four Days’ Marches and the orientation week.’

Genocide in Gaza

The International Court of Justice, the highest court of the United Nations, ruled in May that the Israeli offensive in Rafah needs to stop immediately. This is an interim verdict in the case brought by South Africa against Israel. Earlier, a UN rapporteur announced that there were ‘reasonable grounds’ for assuming that a genocide is taking place in the Gaza Strip.

How do you look back on the encampment?

Van den Bogaard: ‘We’re reasonably satisfied with what we have accomplished. Of course, we would have preferred to see the Executive Board (EB) yield to our demands. However, because of us, the Board was forced to admit that they will maintain ties to genocidal institutions, which means they don’t care how students feel about it.’

Sahin: ‘It was nice to see how various students and employees -even deans- as well as outside people came to the camp to have a chat. We really put something in motion.’

Back to the start of the camp. Unlike in other cities such as Amsterdam and Utrecht, the Nijmegen camp did not immediately result in police intervention. What was different?

Van den Bogaard: ‘I have heard that the Radboud EB was afraid to intervene harshly, for fear of damaging its reputation. That is something to be admired a little; because of it, we could set up camp in peace.’

In the early days of the camp, some protesters interfered with journalists doing their jobs. How do you reflect on that?

Sahin: ‘I think that, in the early days, there was a vicious cycle because both parties had too little respect for one another. Journalists did not respect the protesters’ right to privacy: they didn’t even have time to cover their faces before someone snapped a picture, which is important for their safety. After all, protesters are often looked up online by extreme-right people. Consequently, protesters made comments towards journalists.’

‘I’m not principally against refusing journalists, for example, when a platform like GeenStijl sends reporters to make a scene’

Van den Bogaard: ‘I’m not principally against refusing journalists, for example, when a platform like GeenStijl sends reporters to make a scene. But that was not the case here. Those interactions were very draining in the end; neither protesters nor journalists enjoyed it. Fortunately, we managed to break the pattern by having some good discussions.’

After two weeks came the occupation of a wing of the Erasmus building. Was that a turning point in the protests?

Van den Bogaard: ‘The occupation was comparable to what we did with the camp, as well as the occupation of a hall in the Lecture Hall complex: we invited people for talks. But at the same time, we did escalate matters.’

‘The goal of a protest is not to be convenient for people. We had already been camping on the lawn for two weeks, which was becoming normal for the Executive Board.’

Sahin: ‘It was mainly a way for us to show that the urgency is still there. People are still dying needlessly in Gaza every day. We wanted to change that, which you cannot do by waiting and watching. When Russia invaded Ukraine in early 2022, within eight days all institutional ties had been cut. Why can’t they do the same thing now?’

Some time later, you invaded the office of Board president Daniel Wigboldus in the Berchmanianum building. This happened without any face coverings; why suddenly take off the masks?

Sahin: ‘That came soon after they announced the forming of an advisory committee (supposed to examine international cooperation agreements, eds.). We wanted to show that we are students and really wanted a conversation with Wigboldus in person, not through some committee. It was mainly a symbolic gesture.’

Van den Bogaard: ‘I think it’s very telling how the conversation afterward was mainly about how disrespectful we supposedly were to Wigboldus – especially because we ate his chocolates. The EB’s problem was not the genocide in Gaza or their ties to contributing institutions; it was the fact that we ate their chocolates.’

Sahin: ‘Radboud University has blood on its hands, but everyone keeps working as though everything’s fine. Making a big deal out of some chocolates and calling us disrespectful is the world turned upside down.’

According to the Executive Board, it was very difficult to have a meaningful discussion, because you kept making the same demands.

Van den Bogaard: ‘We would love to discuss and help to think about how to cut ties, but it’s not possible. The EB is as set in its ways as we are. We oppose ties to institutions that contribute to genocide – while they are in favour.’

But isn’t the advisory committee a step in the right direction? Isn’t that the EB meeting you halfway?

Sahin: ‘All that means is the EB is delaying a decision, rather than taking responsibility.’

‘I can’t blame people for choosing to express their emotions in this manner.’

Van den Bogaard: ‘No teachers involved with Situating Palestine (a collective of activist lecturers hosting lectures on the situation in Palestine, eds.) were invited to the committee, despite them repeatedly offering to help. That tells you what the committee’s conclusion is going to be. Not only that, but the process is taking an inordinate amount of time; the committee still hasn’t been set up.’

Aren’t you going too far in saying there is blood on the hands of Radboud University?

Sahin: ‘The EB has been told time and again about their role by both academics and students, as well as their ability to do something about the Gaza genocide. If they then prioritise listening to the government and maintaining ties, that is no longer ignorance; that is a conscious decision to support genocide.’

Another week later, you occupied Thomas van Aquino 1. Tents were put up in the courtyard and the doors were barricaded with furniture. How do you look back on that?

Van den Bogaard, smiling: ‘We announced on our socials beforehand that we would be reorganising the camp.’

More seriously: ‘At that point, people had been putting their heart and soul into the camp but were invariably ignored by the University. It is my understanding that for some people, especially those with direct ties to Palestine, emotions ran high. I can’t blame them for choosing to express it in this manner.’

But there was paint- and ink graffiti everywhere; a firehose had been turned on; furniture was smashed; papers were taken from a locked space and tossed out. A large part of the building was unusable for a while.

Van den Bogaard: ‘I draw the line at what the EB is doing: running from responsibility while a genocide is ongoing. I think it’s almost irrelevant that things were destroyed at protests. The focus should be on why the EB doesn’t take any worthwhile action.’

But isn’t that easy for you to say? Claiming that the destruction of property is irrelevant?

Van den Bogaard: ‘It wasn’t me, but I am the person held responsible. In that sense, it affects me personally because my name is plastered everywhere. So no, I’m certainly not taking it easy.’

‘The people in charge were eager to put a stop to the protests from day one’

Do you, as the face of the protesters, feel responsible for the actions of the collective?

‘Our movement is made up of tons of different people, and things just happen at protests. The main thing is that we reflect on our actions; if things went go, we discuss how to do them differently in the future.’

But actions like this mean antagonizing of the University administration and even the mayor. They are the ones who decide what is and is not allowed on campus; the camp was dismantled that same evening.

Van den Bogaard: ‘The people in charge were eager to put a stop to the protests from day one. The university and the municipality jumped on the first opportunity to get rid of the camp without damaging their reputation.’

Do you feel the mayor was justified in having the camp cleared after the occupation?

Van den Bogaard: ‘Right from the start, we knew that there was a chance that the police would clear the camp at some point; I won’t say it’s an odd decision.’

‘However, what I do find disturbing is the slew of restrictions imposed afterward. Those restrictions became a carte blanche to ban any- and all kinds of protests. Suddenly, there was an issue with lecturers putting up flyers or posters; students wearing a keffiyeh or carrying a Palestinian flag were harassed by security and police; at a discussion meeting an officer threateningly entered the room. Suddenly nothing was allowed anymore.’

You were allowed to protest on parking space P7A. Why didn’t you?

Sahin: ‘We wanted to show that we will not be put in a corner. We want freedom of speech and the right to protest across campus, not just some out-of-the-way parking space. Leaving the lot empty was a statement.’

Some students and employees stated that they felt unsafe due to the protests. How do you feel about that?

Sahin: ‘Many people confuse feeling unsafe with feeling uncomfortable. We were in our camp, and we marched on campus. We did not yell any antisemitic slogans; we just advocated for human rights. I wonder what it is that made people feel unsafe. In my eyes, it’s a matter of comfort, not safety.’

‘If you are pro-Israel, you should be confronted’

Van den Bogaard: ‘I understand that it is difficult to speak out at this time if you’re pro-Israel. But if you’re actively supporting a genocidal regime, should you be surprised if people want nothing to do with you? And yes, there are people who voice their criticism in an antisemitic manner. Don’t misunderstand: I think that’s truly wrong. But that is not what we do. There are also Jewish people involved with the protests.’

‘I can imagine that if you grew up in a pro-Israeli Jewish family, our protests condemn the state of Israel would feel like personal attacks. But Israel is committing genocide. So, if you are pro-Israel, you should be confronted -and yes, that may be uncomfortable.’

Isn’t that just arguing over semantics – feeling unsafe versus feeling uncomfortable?

Sahin: ‘No, it’s about power structures. As a minority, we are acting against a more powerful entity. If you are pro-Israel, you can safely express your opinion because it parrots that of the dominant power.’

‘In the encampment, we had to deal with actual safety concerns. The first week, people came by stating that they would return with clubs to kill us; another group played nazi music at night and shouted “death to Arabs”.’

You invited Mohammed Khatib to the camp, the chair of Samidoun. The German government banned that organisation for ‘antisemitic expression’ and ‘public support of terrorist organisation Hamas’. Khatib was labelled an extremist in Belgium, and his refugee status was revoked. A controversial person, to say the least.

Van den Bogaard: ‘Germany classified Samidoun as antisemitic because they support Palestinian resistance. That does not make them antisemitic, and it certainly does not make them a terrorist organisation. Other countries, including the Netherlands, don’t use the same definition.’

‘Compare it to the claim that the phrase From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free is antisemitic. That’s not necessarily the case. We don’t use it meaning that all Israelis should leave the country. What we want is for there to be a single Palestine where everyone can live, regardless of faith or heritage. In that same manner, Samidoun is an organisation that advocates for political prisoners, which stems from the secular Palestinian movement; something that Khatib emphasised in his camp lecture.’

With summer just around the corner, the mayor’s restrictions have been lifted. What can the University expect in the new academic year?

Van den Bogaard: ‘We would like to have a place where people can come together again and talk about this subject. Whether that will be a new camp, we don’t know at this point. But in any case: The EB better be prepared after the summer.’

Sahin: ‘People shouldn’t think we went away. We will keep up the pressure on the Executive Board as long as they maintain ties.’

Translated by Jasper Pesch

Elsie Green schreef op 14 juli 2024 om 01:48

You don’t get to decide whether someone feels unsafe vs uncomfortable. Feelings are feelings and anyone who is invested in human rights should take care to be empathetic to the suffering on all sides.