The split between Church and University

-

Bisschoppen op het balkon van het hoofdgebouw van de universiteit aan het Keizer Karelplein bij de opening in 1923. Beeld: Katholiek Documentatie Centrum

Bisschoppen op het balkon van het hoofdgebouw van de universiteit aan het Keizer Karelplein bij de opening in 1923. Beeld: Katholiek Documentatie Centrum

Since 16 November 2020 Radboud University can no longer call itself ‘Catholic’. After 97 years the Bishops’ Conference of the Netherlands rescinded the Catholic designation of Radboud University and Radboudumc. The reason is a long-drawn-out conflict about the Catholicism of members of the SKU (Stichting Katholieke Universiteit) Board. How could things get so far? A reconstruction.

Rome, 2 April 2005. In his private apartment on St Peter’s Square Pope John Paul II draws his last breath. This marks the end of a pontificate that lasted more than a quarter of a century. Hundreds of thousands of believers make their way to Rome to attend the popular pope’s funeral. After a one-and-a-half-day conclave, Joseph Ratzinger is chosen as his successor. He takes the name of Benedict XVI.

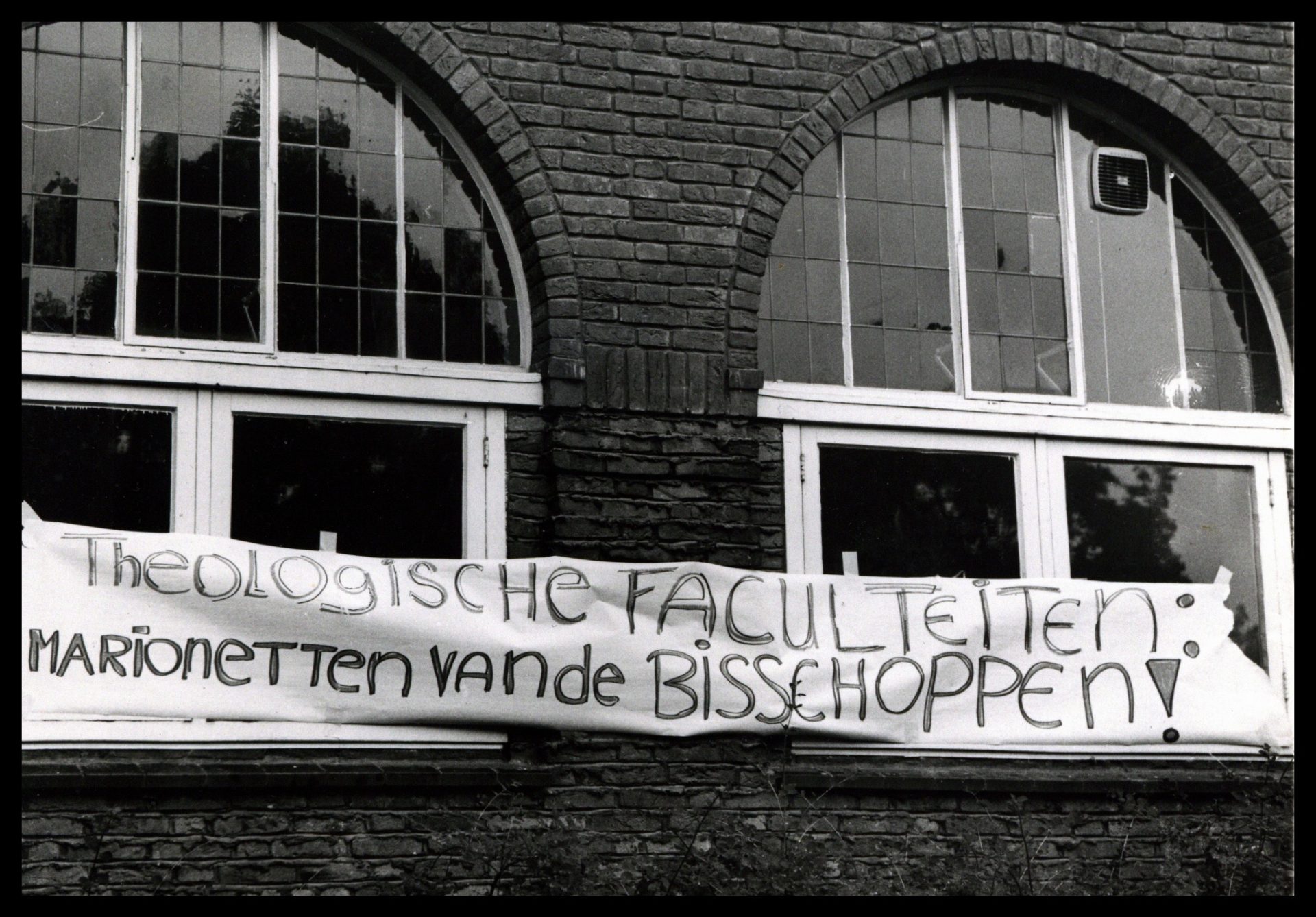

Closer to home, important developments are also afoot in the Catholic world. With increasingly fewer people interested in training to become pastoral workers, teachers of religion or priests, the Dutch bishops wish to merge the three Catholic theological faculties (Tilburg, Utrecht and Nijmegen) into one.

No ecclesiastical degrees

In the autumn of 2005 Radboud University steps out of the negotiations. ‘The bishops wanted to locate the theological faculty in Utrecht – far too far from the Nijmegen campus,’ says Jef Van de Riet, who at the time had just left Tilburg University to become Secretary of the Executive Board of Radboud University. One of his tasks was to promote contact with the Catholic Church.

The bishops are not pleased with Nijmegen’s withdrawal. In December 2006 Radboud University administrators receive a letter from the Vatican informing them that until further notice the theological faculty is no longer allowed to issue ecclesiastical degrees. As of 2007, anyone who wishes to occupy an official position within the Roman Catholic Church must obtain a degree from the Faculty of Catholic Theology in Utrecht or Tilburg. The Faculty’s first Grand Chancellor is Archbishop Wim Eijk who, as we will see, plays an important role in this story.

According to Van de Riet, the failed merger considerably cooled the relationship between the Executive Board and the Dutch bishops. ‘It was an important step in sowing the seeds of the later conflict between the Bishops’ Conference and the SKU (Stichting Katholieke Universiteit) administrators.’

Working visit

The ties between the University, Radboudumc and the bishops do not deteriorate dramatically in the years following the failed merger. When Cardinal Adrianus Simonis retires in 2007, Ad van Luyn succeeds him as President of the Bishops’ Conference of the Netherlands. As a Radboud University alumnus, Van Luyn is committed to the tradition of an annual working visit of the Bishops’ Conference to Nijmegen. On these occasions the clergymen are given a tour of the Campus, followed by a joint lunch. On the agenda are talks with the SKU Board, the Executive Board and the Executive Board of Radboudumc concerning the University’s identity, and sometimes a visit to Radboudumc.

These visits come to an abrupt end when Wim Eijk is appointed Archbishop of Utrecht in 2008 and goes on to act as President of the Bishops’ Conference from 2011 to 2016. ‘From that time onwards appointments were often cancelled or postponed,’ says Van de Riet.

What next?

What will happen to the identity of Radboud University now that it has lost its ‘Catholic’ designation? Does this mean the end of the prayer at academic ceremonies? Will the cross disappear from the University’s logo? Concerning these and other questions, the Executive Board would like to have some input from the rest of the Campus. “This process will take until 2023,” said Wilma de Koning on 16 November during an online meeting of Radboud Reflects. This time is needed, says the Vice President, to create the space for an extensive campus-wide dialogue, as was done in the past regarding the University’s new strategy and the leadership memorandum. This means the University will be able to present its new identity on the occasion of its centenary.

Another contact point with the bishops also disappears shortly afterwards. In his role as Bishop of ‘s-Hertogenbosch and local bishop, Antoon Hurkmans plays an important role in acting as a bridge between the Bishops’ Conference and Radboud University. When he is forced to step down due to fatigue and other physical symptoms, he asks priest and Professor Antoine Bodar to take over and maintain contacts with the higher education institutions and student chaplaincy. ‘Bodar took his duties in this respect seriously, but he was often abroad and wasn’t a member of the Bishops’ Conference,’ says Van de Riet. ‘As a result, many places where the bishops and the University could meet informally disappeared. The situation improved with the appointment of Gerard de Korte, but in hindsight this came too late.’

Not married in church

Let’s go back for a moment to Pope John Paul II. On 15 August 1990 he had issued the Ex Corde Ecclesiae, an apostolic constitution (legislative document) with guidelines concerning the criteria a Catholic university had to meet according to the Vatican. According to this document, research at a Catholic university should include a theological perspective and students should be trained to become good Christians.

In 2009, nearly 20 years after the publication of this apostolic constitution, the Bishops’ Conference articulates in a report what this meant for a Catholic university in the Netherlands. And it meant a lot. For example, the majority of the university’s Executive Board must consist of Roman Catholics who play an active role in the Church community and are committed to embodying the practical implications of their university’s Catholic identity. A Catholic university must also endeavour to appoint Roman Catholics to the majority of vacancies for academic and supporting staff.

Five years later, the new policy elaborated by the Dutch bishops forms an obstacle for Radboud University: on 1 November 2014, Tini Hooymans’ second term as member of the SKU Board responsible for Education & Research comes to an end. To ensure a smooth succession, the SKU Board already have a successor lined up: Geert ten Dam, then President of the University of Amsterdam. Some eyebrows are raised among SKU Board members when the bishops request more information about the candidate, including her religious denomination, marital status and baptism certificate. A few weeks later the bishops reject the candidate’s nomination. “The candidate has an impressive CV,” they say in their letter. “However, upon inquiry it has come to the bishops’ attention that she was not married in church. It goes without saying that this is a pre-condition for the bishops to accept such an appointment.”

The bishops’ rejection causes indignation among SKU Board members. In June 2015 an interview follows between the SKU and the Bishops’ Conference and a month later between Geert ten Dam and Jos Punt, Bishop of Haarlem-Amsterdam. It is a constructive talk, but the bishops stand by their position. “Her remarkable qualities and expertise are clearly beyond doubt as far as the bishops are concerned,” says the letter that follows. “However, the interview with the local bishop revealed that the bishops’ objection to her appointment as member of your board, namely the fact that Ms Ten Dam was not married in church, can unfortunately not be remedied.”

Appointed as advisor

The SKU Board decides to try a different approach. On 30 August 2016 they put forward former Rector of the University of Amsterdam Dymph van den Boom for the vacancy. But the bishops once again refuse to appoint the candidate, this time because “she does not identify as religious” and “would not make a strong contribution as far as Catholicism is concerned”.

In the following months a number of dialogues take place between the two parties, but their positions remain widely divergent. The SKU proposes in future appointing only one of its board members to promote ecclesiastical interests. This person alone would bear the burden of the strict ecclesiastical criteria set by the Bishops’ Conference. The bishops reject this proposal outright and put forward their own list of candidate board members, all of whom are rejected by the SKU Board on the grounds that their own candidates are more suitable. Since the bishops continue to refuse to appoint Dymph van den Boom, the SKU Board appoints her as advisor for Education & Research. Van den Boom is not an official member of the SKU Board, but she has the same duties as regular board members.

Interview in Rome

With the dialogue with the Dutch bishops running into the same deadlock time and again, in the summer of 2017 an SKU delegation visits Rome to submit the case to the Congregation for Catholic Education, the Vatican’s Ministry of Education. In the Palazzo della Congregazione, which borders on St Peter’s Square, President Loek Hermans, Secretary Berthe Maat, Vice President of the Executive Board Wilma de Koning and Jef van de Riet are warmly welcomed by Cardinal Giuseppe Versaldi and Father Friedrich Bechina. ‘Rome was of the opinion that Radboud University formed an important link in the global network of Catholic universities,’ says Van de Riet.

During the two-hour interview, the Nijmegen delegation is given ample opportunity to share their side of the story. ‘We explained that it was important to us that our Executive Board members were first and foremost good administrators,’ says Wilma de Koning. ‘And that it was nearly impossible to find such candidates who also happened to be good Catholics in line with the criteria of the Bishops’ Conference.’

‘We really felt heard in Rome’

The Cardinal and Father listen carefully and seem to show understanding for the university administrators’ position. They say it is quite common for such problems to arise within an ecclesiastical province and offer an example from South America. ‘Our problem was not in Rome; we really felt heard there,’ says De Koning.

Transgender centre

Following the SKU’s visit and an interview with the bishops, the Congregation puts forward a proposal for mediation. To ease the conflict, a temporary Committee of Good Offices was appointed. This Committee proposed a modified appointment procedure, in which potential candidates were jointly discussed by representatives of the Bishops’ Conference and SKU representatives. Both parties accepted the proposal. The Committee consisted of two church officials representing the bishops, and two members of the SKU Board.

In the meantime, another development in Nijmegen was causing the bishops displeasure: the proposed opening of a transgender centre at Radboudumc. When the SKU announced Radboudumc’s intention to open this centre, the bishops replied that such a step was “entirely unnecessary”. A striking detail: within the Dutch Bishops’ Conference, it is Cardinal Eijk who is responsible for medical and ethical questions.

In the years that follow all attempts to find a solution for SKU board vacancies via mediation fail. On 17 June 2019, the SKU Board put forward for the last time four candidates, including current President Wim van der Meeren, only to be turned down once again.

Press release

By the spring of 2020, this rejection of candidate members of the Board has been going on for six years. It’s a total impasse. The SKU Board only has six members, one too few according to its own statutes. The term of three members, including President Loek Hermans, must be prolonged for lack of a successor. The SKU Board is tired of the situation, and in the spring of 2020 they take the case to the Enterprise Chamber, a court that rules over Dutch corporate disputes.

All the members of the SKU Board attend the court proceedings, while the bishops are represented by their lawyer and a church official. Once again, it becomes clear that the positions of the two parties are irreconcilable. The bishops’ intractable stance causes so much irritation among SKU Board members that President Loek Hermans hints that Radboud University might consider becoming a National University.

On 21 July the Enterprise Chamber reaches its decision: the SKU is allowed, temporarily, to appoint its own members, without the bishops’ approval. With this ruling, the Catholic Church loses much of its hold on the University. Shortly afterwards the SKU appoints four members who have been waiting in the side lines for a long time, including Dymph van den Boom and Wim van der Meeren. In the same week a decree from the Bishops’ Conference lands in the SKU mailbox on the Geert Grooteplein, announcing that the bishops are rescinding the Catholic designation of the SKU.

‘There is something about this decision that doesn’t make sense to me’

Wilma de Koning still doesn’t understand it. ‘There is something about this decision that doesn’t make sense to me,’ she says. ‘At other Catholic institutions in the Netherlands it is enough if the bishops appoint one supervisor, but not in Nijmegen.’

‘Cardinal Eijk has very strict views on the Catholic faith and how it should be practiced. He’s been heard saying that a single Catholic university in the Netherland is enough. And that’s what we have now.’

There was always tension between the bishops and the University

The tension between the bishops and the University has been around for a very long time, says University Historian Jan Brabers. In a way since the Catholic University Nijmegen was first founded in 1923. ‘In the early 20th century some groups wanted to form a Catholic university. The bishops took the initiative by creating the St Radboud Foundation in 1905. As with many Catholic organisations, their motives were twofold: they also wanted to keep control of the University.’

At the time the bishops themselves were not university graduates – they had only attended a seminary. ‘Science was something liberal, civil and hostile: the opposite of Catholicism,’ says Brabers.

This tension broke to the surface as soon as the University was founded in 1923. Jos Schrijnen, priest and formerly Professor in Utrecht, was appointed as the first Rector Magnificus. As a classicist who attached considerable importance to academic freedom, Schrijnen also wanted to appoint non-Catholic professors, for example for subjects like linguistics. He wanted to call the University the Emperor Charlemagne University, an internationally recognisable name linked to Nijmegen. But the bishops wouldn’t allow it. Brabers: ‘Schrijnen thought the name ‘Catholic University’ was too oppressive.’

In the period after the University’s foundation, the bishops were responsible for the day-to-day management of the University, including the appointment of professors. Too ambitious professors were discouraged, including Willem Pompe, who was appointed Professor of Criminal Law in 1923 and had hopes of conducting research on criminal psychiatry and criminology. ‘The bishops found all this Freudian stuff too scary and refused to fund it. After five years, Pompe left for Utrecht, where he went on to become very famous for his ideas.’

At the University, there was a feeling right from the start that it was important to keep the bishops at a distance. Brabers: ‘Professor of Literature Gerard Brom said once: ‘We can’t live without them, but we can’t live with them’, a view shared by many professors. The professors tried to keep the bishops out of the picture as much as possible. It was a difficult relationship, not in the least because the professors were convicted Catholics themselves.’

Shortly after the Second World War the University went through a substantial growth spurt with the creation of two new faculties: Medicine and Physics. Around this time the bishops relinquished the day-to-day management of the University. ‘They saw that the University was perfectly capable of taking care of itself,’ says Brabers. ‘Priest and Professor Reinier Post was appointed first President of the Executive Board. He guided the University through this period of expansion in the 1950s.’

A change in the Higher Education Act in 1961 led to the creation of the Stichting Katholieke Universiteit (SKU), which took over the bishops’ tasks regarding the University and hospital. The bishops officially still had the authority to oversee the appointment of professors, but they no longer did so in practice.

‘The bishops fully embraced this transition. They had for a long time been aware of the fact that the University was growing and could manage perfectly well without them. The then Archbishop, Cardinal Bernard Alfrink, was a progressive open Catholic who had been Professor in Nijmegen himself. It was all very different from today’s situation.’

According to Brabers, the bishops retained their moral authority for a long time. ‘At the hospital too, when ethical issues arose, people looked to the bishops.’

De facto, the bishops had resigned from managing Catholic universities. In Nijmegen and Tilburg they retained the right to appoint members of the Supervisory Board, a task performed by the Minister of Education at other Dutch universities. This remained the case until July 2020, when the Bishops’ Conference lost a court case against the SKU in the Enterprise Chamber and rescinded the University’s Catholic designation, thus placing itself entirely outside the University and Radboudumc.