Where does the university’s tap water come from?

-

Heumensoord. Photo: Tom Hessels

Heumensoord. Photo: Tom Hessels

When you take a mouthful of tap water at Radboud University, you’re drinking water from Heumensoord. The woodland and heath area adjoining the Campus is a source of this water, supplying 150,000 people in Nijmegen and surrounding municipalities every day.

How much of the water extraction operation in Heumensoord is visible?

Heumensoord is a five hundred hectare woodland and heath area. Many people in and around Nijmegen walk their dogs there every day among the pines, beech and rhododendrons. The water extraction operation is nearly invisible, which is exactly the intention.

If you look carefully, you will see large square metal covers at various places in the forest. Under these are securely sealed and protected wells.

Under the covers are cellars, two metres deep, containing a pipe that brings the water up from the ground, makes a 90° turn, and transports it towards the pumping station located on the edge of Heumensoord.

How deep is the pumped water?

The groundwater under Heumensoord is located twenty metres below ground level. The water pumped in the forest is phreatic groundwater: the first layer of water you run into when digging a vertical well. In the case of Heumensoord, this is rainwater that seeps through the ground until it reaches the phreatic groundwater layer. From there it flows to the drinking water wells or surrounding surface water like the Maas-Waal canal.

‘We have a licence to extract 10 million m3 of water per year from the Heumensoord forest,’ says Van Kessel. ‘In the past year, we extracted 9.2 million m3 of groundwater. This required some forty water extraction wells.’

How old is the tap water?

The age of our drinking water depends on the speed with which rainwater seeps through the ground. An example: in some places in Heumensoord there are signs saying ‘groundwater protection area’. The rainwater that falls in these areas takes approximately 25 years to reach the wells. ‘Half the water we pump comes from this area, so it’s a maximum of 25 years old,’ says Van Kessel.

Groundwater also flows into the wells from outside the groundwater protection area. The groundwater from this area is between one hundred and four hundred years old.

Can the pumped water ever run out?

No, that’s impossible. In Heumensoord, 3000 m3 of rainwater falls per hectare every year. This water flows to lower surrounding areas, and then via canals, ponds and rivers, ultimately to the sea. The water pumped by Vitens is removed from this cycle and supplied to clients. ‘Once they’ve used it, it flows to the sewer, and from there to the river and ultimately the sea.’

So pumping water means less water in nature. ‘These interests are taken into consideration when applying for a licence to pump water,’ says Van Kessel. ‘It changes the balance, the rainwater doesn’t run out, but there’s a bigger impact on the environment.’

Is the pumped water filtered?

Rainwater seeping through the ground absorbs all kinds of substances, like iron and manganese. The Heumensoord water is also naturally acidic, which is not good for pipes and kitchen appliances. These substances are removed from the water through sand filters and by airing the water.

Van Kessel: ‘We do this with filtration tanks in the production building located at the edge of the forest. There, the water also flows over marble grains to absorb some calcium, which deacidifies it.’

How does the water end up in our taps?

The amount of water supplied by Vitens depends on the number of people who turn on their taps. This varies from day to day and hour to hour. Especially in spring and summer people use lots of water, and on working days most people take a shower sometime between 7 and 8 am.

Vitens must at all times be able to deliver a little more water than needed on a ‘maximum day’ (the day on which clients use most water, Eds.). This is why they also store a large quantity of clean water in a number of cellars. ‘If we were all to turn on all our taps at the same time, some of the water would come directly from the production process and some from the cellars,’ says Van Kessel. At night, when fewer people use water, the cellars are once again pumped full of water.

After the pumping station and the cellars, the water is carried through a number of large transport pipes and many small, narrow pipes into people’s homes. In the five Dutch provinces where Vitens is active, there are nearly fifty thousand kilometres of underground pipes – more than the Earth’s circumference.

There is a shooting range at Heumensoord. During the Four Days Marches, soldiers set up tent camps in the forest, and from September 2015 until April 2016, it was home to three thousand refugees. Is none of this a problem for water extraction?

Extensive activity in the water extraction area can indeed be a problem. The military tent camps are located in an area where water flows to the pumping wells at a very fast rate. In principle, only activities related to drinking water extraction are allowed there, but the provincial government makes an exception for these parties.

‘Everyone wants safe drinking water’

Vitens always enters into dialogue with parties who come in the vicinity of the wells. ‘Luckily everyone wants safe drinking water,’ says Van Kessel. ‘Together with the Province and the parties involved, we consider what additional measures are needed to prevent the water from becoming contaminated with bacteria or chemicals.’ Working with fuel is dangerous, for example, so all energy should ideally come from the power grid or protected generators.

In the area surrounding the pumping wells, it’s essential that no dangerous substances leach into the ground, such as heating oil from old tanks. ‘For every human activity, we look at the consequences for the groundwater,’ says Van Kessel. ‘Normally, the soil is sufficiently protected against bacteriological pollution. But once you start digging holes, that’s no longer the case. This is why Vitens asks everybody – even hikers – to be vigilant and report any suspicious activity in the forest.’

What is the quality of the Heumensoord water?

‘The water being pumped in Heumensoord is of good quality,’ says Fons Smolders, Professor by Special Appointment in Applied Biochemistry at Radboud University and senior project leader at research centre B-Ware.

What is striking is that the concentration of nitrate in the water is relatively high, though still well within the norm for European drinking water. ‘This is due to the fact that coniferous forests capture a relatively high amount of atmospheric nitrogen in the trees’ needles,’ he says. ‘When it rains, the nitrogen, together with rainwater, washes as nitrate into the groundwater. Although nitrogen deposition onto a solid surface has decreased since the 1980s, it’s still far too high. Luckily nitrate isn’t dangerous for people, especially not in such relatively small quantities.’

For the natural world, it’s a different matter. Nitrate concentrations like those measured in Heumensoord can lead to severe problems in natural areas supplied with this groundwater. Incidentally, nitrate in the groundwater doesn’t just come from forests. Agricultural land also leaches too much nitrate.

Do we use too much water?

Water usage hasn’t really increased over the past twenty years, but Vitens observes a shift in the last few years. ‘People once again enjoy taking long showers,’ says Van Kessel. ‘What’s more, half the water we use is heated. Water conservation is not only important because of the water, but also because of the energy required. That’s why we ask people to use drinking water sparingly, especially when showering or using the washing machine.’

Research in the 1990s showed that student houses used a lot more water than an average family. ‘This is probably due to the showering culture,’ says Van Kessel.

Does the drinking water in the Huygens building really come from Heumensoord?

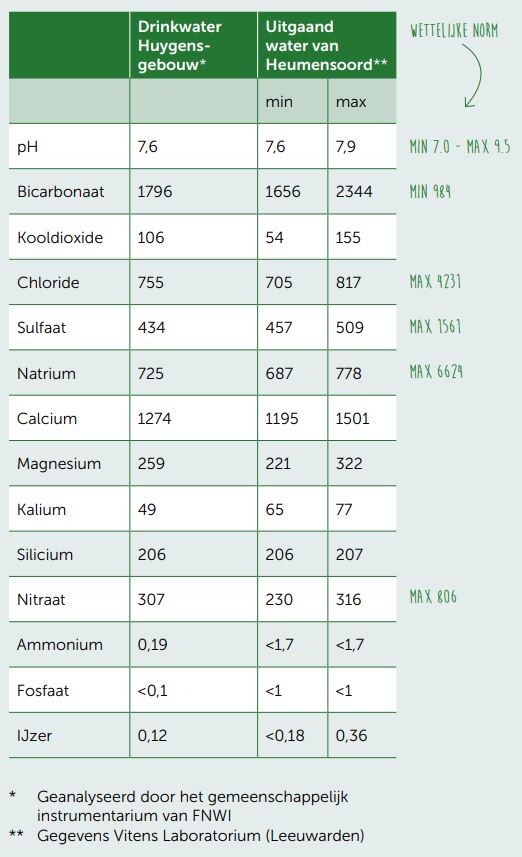

To test this, researcher Sebastian Krosse from research centre B-Ware compared a sample of tap water with the minimum and maximum values of water coming out of the Heumensoord drinking water station in 2019. “There’s only one possible conclusion,” says Krosse. “The drinking water in the Huygens building is in fact very similar to the Heumensoord water.”