Why the real German doesn’t exist

What exactly is a German? Well, the obvious answer would be that a German is a person from Germany. The real answer to quintessential Germanness, however, is a bit more complicated.

I would definitely call myself a German. After all, I was born in 1998 right in the middle of the more-or-less freshly reunited country next to the Netherlands.

I also spent the first eighteen years of my life in the same tiny German village, I hold a German passport and my last name is a literal German adjective. But despite this level of immersion in German culture, the essence of Germanness continues to evade me.

This article is part of the newest Vox paper edition. Starting this week, it’ll be available all over campus. In this edition, we’re looking for both similarities and differences between German and Dutch citizens. Or: does the stereotypical German even exist?

What is it that the more than eighty million people currently residing in the Federal Republic of Germany (Germany’s official name) truly have in common? How can you find a single uniting characteristic between East and West? The South and the North? Berlin and the rest of the country? To answer this question, you have to dig deep into the culture of wearing Birkenstocks with socks, sourdough bread, and grammar that no one understands.

Not German

Maybe the best way to identify the essence of true Germanness is by establishing what isn’t German. But sometimes, even that turns out to be more complicated than you might think. Take for example Birkenstocks, sourdough bread, and Grammar that no one understands: all of those things seem very German at first, but once you look a bit closer, they turn out to be not German at all.

‘Sourdough bread was invented more than six thousand years ago in Egypt’

Birkenstock has been owned by an American equity firm since 2021, sourdough bread was invented more than six thousand years ago in Egypt, and Germans share their language’s impossible grammar with the Swiss, the Austrians, and some people in Belgium and Luxembourg. So what remains if even the most German things turn out to be not German at all?

Federal republic

Let’s start from the beginning. As the name suggests, the Federal Republic of Germany consists of sixteen federal states. Only thirteen of those are actually states; three are city-states, including Berlin, Hamburg, and, for reasons unknown to many, Bremen.

The west German states are generally wealthier than the east German states – unless you live in the Saarland, which just got unlucky. The South is the wealthiest, mainly thanks to the German car industry – and especially Bavaria can be a bit smug about that. So much so that they have their own Bavaria-exclusive party and sometimes threaten to become a country in their own right.

The South, especially Bavaria, is also what most foreigners associate with the typical German: Lederhosen, Dirndl, and Oktoberfest included. Except for the famous Prussian attitude – that’s mostly from present-day Brandenburg, the region around Berlin, at the other end of the country.

Statistically, however, most Germans are from North Rhine Westphalia (which is also where a lot of German students at Radboud University come from). And, historically, some of the most important Germans, including Nietzsche, Bach, Luther, Schiller, and Goethe all worked in Thuringia. Where on earth is Thuringia? You might ask yourself. Don’t worry, most Germans regularly forget about its existence too. I should know, it’s my home region.

Religious enigma

Germans in the West of the country are generally more religious than in the East, mainly thanks to four decades of Socialism that have left the East mostly atheistic. On the Christian spectrum itself, the West is more Catholic, the East more Protestant and overall, 42 per cent of Germans are not affiliated with Christianity whatsoever. And despite almost half of Germany being non-Christian, Angela Merkel’s Christian party ruled the country for sixteen years.

‘Part of German religious identity is not being able to agree on it’

If you are now confused about German religious identity, we are on the right track. Having a lot of questions about German Christian identity is exactly why Martin Luther wrote a very long letter, refused to apologise to the authorities, and then hid in a castle while translating the Bible for eleven months, laying the foundations for Protestantism.

Part of German religious identity is not being able to agree on it, which is why the West and the East celebrate different religious holidays. What does remain the same, however, is that most Germans only see the inside of a church for (a) weddings, (b) funerals, and (c) Christmas mass, where the long tradition of sitting through a poorly acted primary school production of the birth of Jesus takes place once a year.

Lost in dialect

But wait! I hear some of you say. Go back to what you said about the translation of the Bible. Isn’t that the origin of a written standard of the German language? And yes, indeed, you would be right. Most Germans do speak German and we do agree on how to spell it (well, at least until the standard German dictionary Duden decides to change their mind about that again).

Of course, not everyone who speaks German is necessarily German, but let’s disregard this for the moment. The German language is definitely something Germans do have in common. At least if we can understand each other. Understand each other? Yes, exactly, welcome to the world of German dialects.

In the North, German sounds suspiciously close to Dutch, the more you get to the South, the less you will be able to understand anyone at all, and when I get emotional, my friends have pointed out with great delight and fascination that I start to Sächsel, which is the Saxonian dialect that everyone confuses with my Thuringian one because, as we have already established, no one ever remembers Thuringia.

The Nazis

So far, most German things have turned out to not be German, we have established that there is barely religious, political, or linguistic unity – and not even German clichés are something we can really agree on. What remains, then, in terms of Germanness? Well, it’s time to address the elephant in the room: modern German history.

Their shared history, one might say, is what truly unites the people of a country. And in the case of Germany, the most prominent part of that history includes some of the most atrocious acts in human memory. And let me be perfectly clear, most Germans take this part of their history very seriously.

‘A shared Nazi past and the historical responsibility that comes with it can’t be the core of Germanness’

At the same time, a shared Nazi past and the historical responsibility that comes with it can’t be the core of Germanness, either. It might be a defining moment in German history, but ancestorial participation in the Holocaust is not the definition of what a German is. If it were, we would have to disregard all the people that the Nazis precisely didn’t want you to associate with being German.

It would disregard the histories of German Jews, Black Germans, and Germans of Colour. It would also do injustice to Germans with mental and physical disabilities, to gay, lesbian, bisexual, nonbinary, and transgender Germans, socialist and communist Germans. Put differently: a lot of past and present Germans that some fascists eighty years ago decided to erase from the definition of what a German is supposed to be.

Not to mention that there are quite a number of Germans whose families moved to Germany decades after the end of the Second World War. Would they be less German because their grandparents and great-grandparents were not part of those decades of German history? I don’t think so.

True Germanness

Does the real German not exist, then? After all, Germanness, with all its contradictions, continues to evade a definition. At the same time, there is something about Germany that does make me feel like I am returning home every time I cross the border.

Maybe there is some quintessential Germanness, some part of universal German culture, a way of being German that cannot be defined through the usual suspects that you would usually quantify a culture with. But what is it, then, the universal feeling of being German?

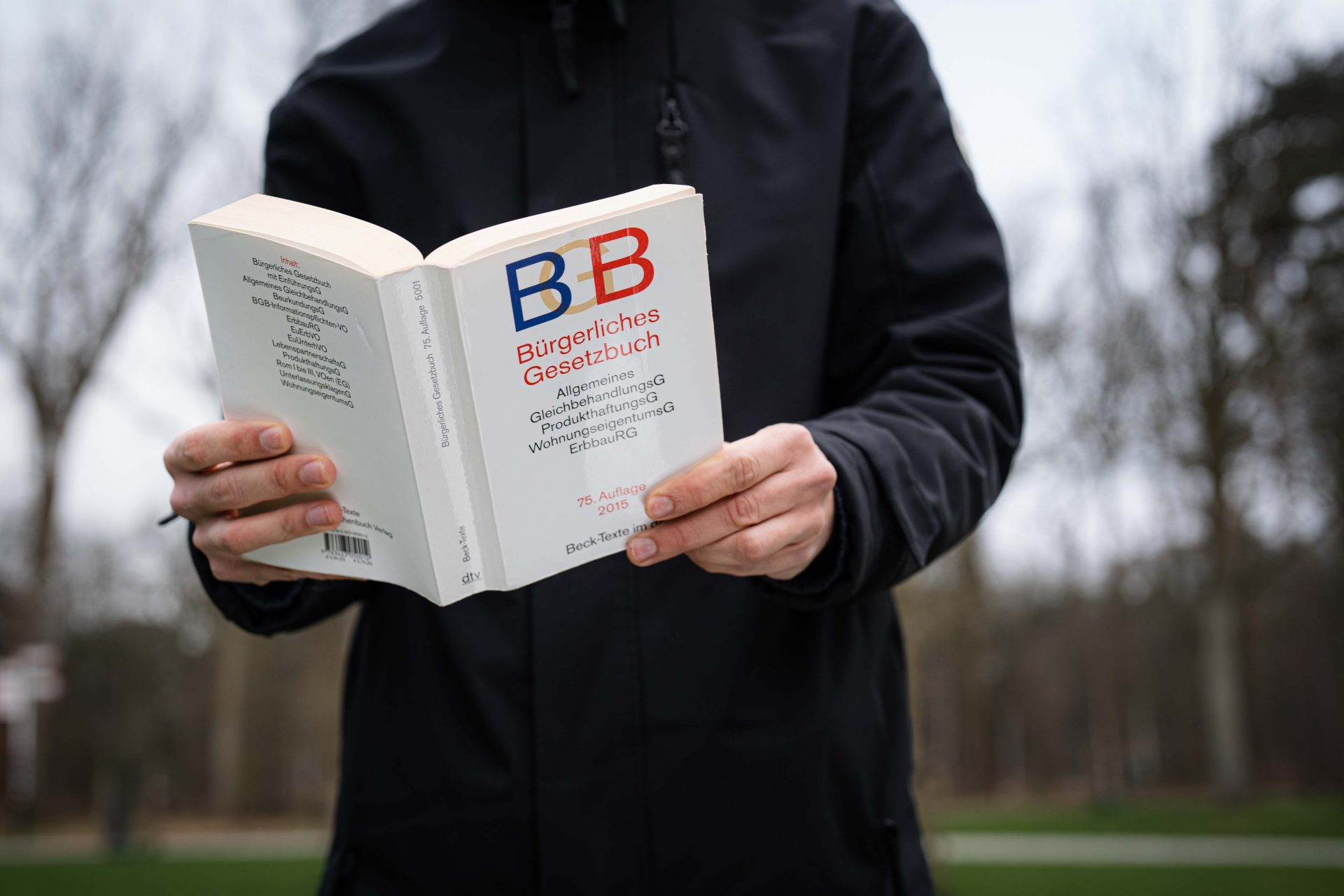

To find out, you have to venture into the depths of German public service buildings that have not been renovated since the early 2000s, but look like they are from the 90s. You have to try making an appointment at a German municipal office that is only open during a two-hour window every third Wednesday following a full moon.

‘German bureaucracy is truly unique’

You have to interact with the German driving licence office or the office for student finance or, in fact, any administrative body in this vast country. You have to have someone look you straight in the eyes and tell you the way to communicate with an official German office in 2023 is by fax.

Only when you have come up against the monster that is German bureaucracy and asked yourself halfway through if you, too, would be capable of voluntary manslaughter, have you experienced the essence of Germanness. No matter the religion, dialect, political or sexual orientation, colour of your skin, or federal state of your origin, the sheer insanity of German bureaucracy is something so inherently German that I have yet to see it replicated. And it may just be what unites all of us – Germans of the past, the present, and, probably, the future.