Women don’t like catcalling, but some men believe they’re paying women a compliment

-

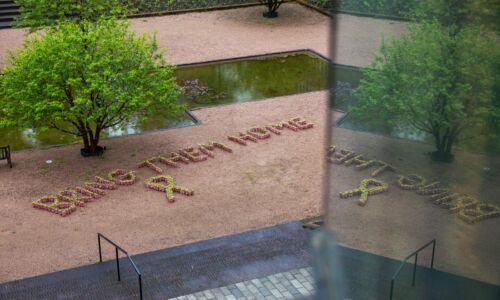

Afbeelding ter illustratie. Foto: Johannes Fiebig

Afbeelding ter illustratie. Foto: Johannes Fiebig

Whistling as a woman walks past, or calling her a ‘hot babe’. It is usually men who engage in this kind of behaviour. But why do they do it? To show off their virility, for example. Or because they think they’re flirting, in which case, they don’t even mean for it to be offensive.

What behaviour do you find most offensive in men? Catcalling, answered four out of five students writing their Bachelor’s thesis with Max Primbs (PhD candidate in Social and Cultural Psychology). This led them to the idea of conducting a study on this phenomenon. Their remarkable conclusion: half of the Nijmegen men who engage in catcalling believe they are paying women a compliment.

‘A loud whistle or a comment of a sexual nature made by a man to a passing woman,’ that is the Oxford Dictionary definition of a catcall. The term originally referred to expressing dissatisfaction with a theatre performance by whistling or shouting at the actors on stage. ‘But there are as many definitions of catcalling as articles written about it,’ says social psychologist Primbs. ‘One thing all the definitions have in common, though, is that this is unwelcome behaviour.’

Catcalling is usually something men do to women, says Primbs. The other way around happens only very rarely. It is something that most women will experience at some point, especially younger women and teenagers.

Aggression

Students Johanna Kube, Renée Derix, Céline Epars, Hanna Schuller, and Fenne van Geene chose to devote their thesis research to examining the causes, consequences and background of catcalling. They also looked at ways to reduce catcalling, since this kind of shouting and whistling is anything but innocent. Primbs mentions research showing that women who are the victim of catcalling experience negative consequences and physical symptoms such as nausea or increased muscle tension.

‘As a victim, you feel powerless, because if you say anything, you risk triggering further aggression’

‘As a victim, you feel powerless, because if you say anything about it, you risk triggering further aggression. Catcalling can lead to self-objectification, and even a negative self-image. Victims tend to feel less safe, and report a higher general anxiety level. Women also tend to avoid places where street harassment is known to happen.’

Nijmegen students Yana van de Sande and Judith Holzmann have launched Catcalls of Nimma to raise awareness of street harassment. ‘It’s about women being sexualised and objectified, but also members of the queer community being insulted on the street,’ says Holzmann, who has by now graduated. By, for example, chalking some of the catcall texts on the street, Catcalls of Nima wants to literally and metaphorically bring people’s attention to street harassment. Holzmann: ‘While we were chalking, we ended up talking to a man who genuinely thought he was paying women a compliment; he didn’t realise what it was like for the women.’

Virility

It’s true that most catcallers don’t feel guilty, as the researchers concluded on the basis of a public survey. Approximately half of the men who engage in catcalling have no intention of leaving a negative impression. Of the surveyed men who admitted to catcalling, 30% said they thought they were flirting, and 20% thought they were paying women a compliment. Primbs: ‘These men may not mean to offend, but their behaviour still has negative consequences. The other half of the men did it for different reasons, for example as a display of power, or to show off their virility to their friends.’

Other well-intentioned initiatives are campaigns against catcalling, says Primbs. He’s referring to an add by L’Oréal, entitled ‘Stand Up Against Street Harassment’. At first sight, the add looks like a great instructive video, but things go wrong in the voice-over: ‘78% of women have experienced sexual harassment in public.’ Psychologists know that this sends catcallers and potential catcallers the implicit message that what they do is the norm. Primbs: ‘This tends to have a counterproductive effect.’

Education can help victims to understand that it’s not their fault, says Yana van de Sande, of Catcalls of Nimma. ‘And it’s important that bystanders intervene in a friendly way.’ Holzmann: ‘If that’s not possible, you could at least speak to the victim and ask her if she’s ok. It’s all about recognising that what just happened isn’t normal. We’re responsible for each other’s safety on the street.’

Group pressure

The survey they conducted brought Primbs and his students face to face with a difficult paradox. ‘Most men distance themselves from catcalling, yet most women report experiencing it. There are two potential explanations for this: either there is a very small group of active catcallers, or there is a difference between the men’s socially acceptable answers and their actual behaviour. Probably, it’s a mixture of both.’

‘Men who want to demonstrate their power won’t stop catcalling just because it’s made illegal’

The researchers suspect that catcalling is related to age and education level, but also and foremost group pressure. Primbs: ‘Even if you’re highly educated and you understand that it’s wrong to shout after people on the street, you may still succumb to group pressure.’

The 50% of catcallers who have no bad intentions are susceptible to interventions aimed at changing their behaviour. In other words: progress is possible. One option is for the police is issue fines. In Rotterdam and Arnhem, street harassment is already a punishable offence. Primbs: ‘Men who want to demonstrate their power won’t stop catcalling just because it’s made illegal, but men who do it due to lack knowledge can be swayed by such measures.’ Catcalls of Nimma also sees the potential benefit of making catcalling punishable.

Van de Sande: ‘I know that it’s hard to enforce, but it still sends out a signal that this is socially unacceptable behaviour. Ultimately, street harassment is a problem for everyone. Through education aimed at young people, but also for example in workplaces, we can open the dialogue on where the boundaries lie, and teach people that compliments are welcome, but that it all depends on what you say and in what context.’