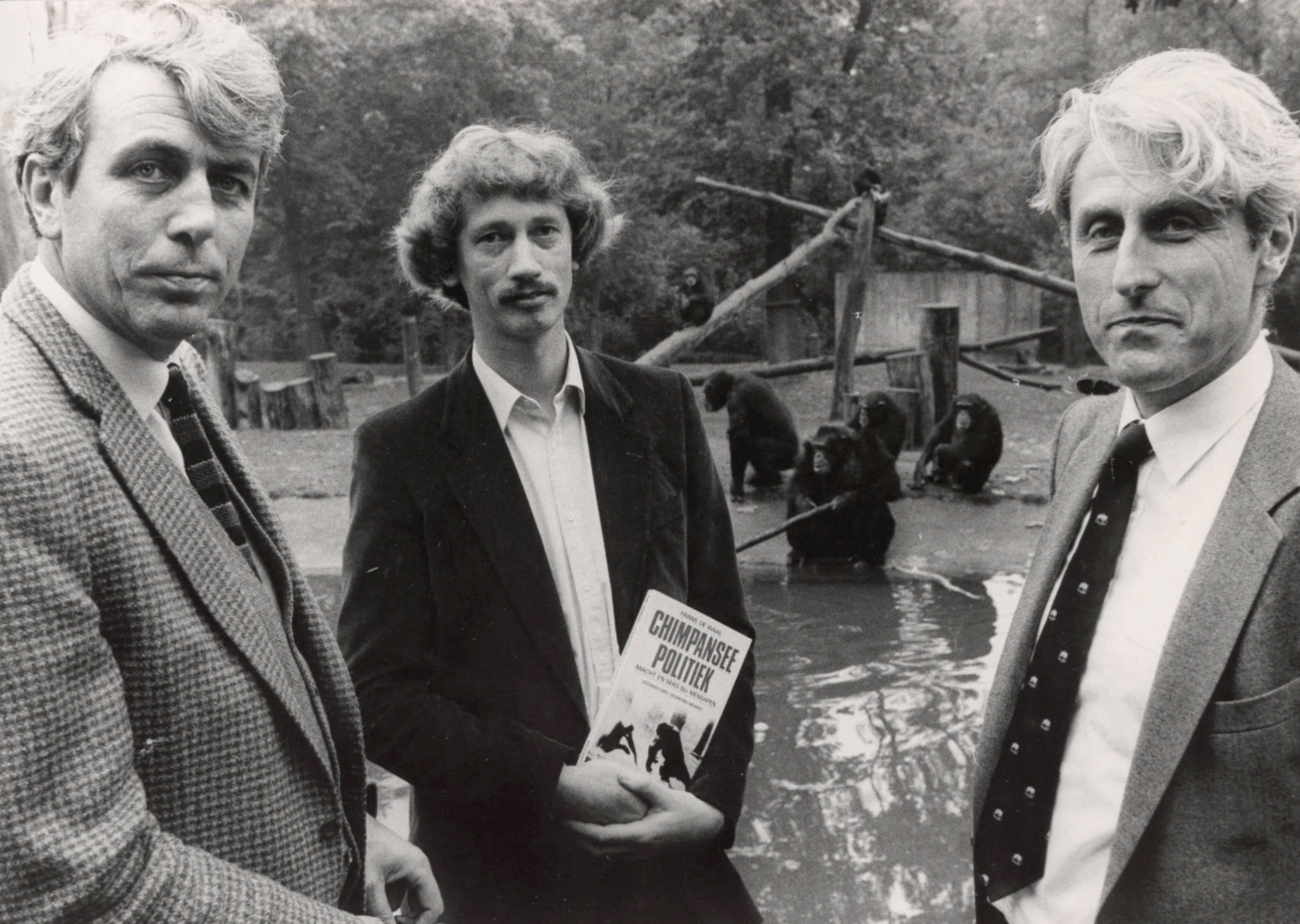

Frans de Waal: ‘It was love at first sight’

-

Photo's monkeys: Theo Kruse, Burgers' Zoo

Photo's monkeys: Theo Kruse, Burgers' Zoo

Frans de Waal met his first chimpanzees at Nijmegen University, where the now world-renowned primatologist studied biology in the late 1960s. Even then, he already knew that animals are smarter than we think.

His first encounter with chimpanzees took place in the Spinoza Building in Nijmegen, where two young apes lived on the top floor. They could be seen walking hand in hand with researchers through the corridors on their way to a research session. ‘Sometimes they escaped, which caused a lot of commotion’, says Frans de Waal (68). The world’s best known primatologist studied biology in Nijmegen in the late 1960s. The apes belonged to psychologists, who studied their behaviour. De Waal, a great animal lover, helped with their research to earn some additional income. ‘It was love at first sight’, he writes in his latest book. ‘I had never encountered animals who knew so clearly what they wanted.’

‘It was love at first sight’

The chimps mostly just wanted to play. Instead, they were stuck in small cages with no outdoor space. ‘This would never be allowed now’, says De Waal. ‘Apes have to be kept in groups whenever possible. They are social animals.’

Frans de Waal has been living in the US for many years now, where he is Professor in Psychology at the Emory University in Atlanta and director of the Living Links Center, a component of the Yerkes National Primate Research Center. This centre accommodates 3500 primates, mostly in spacious enclosures, for biomedical and behavioural research. Our interview takes place over the phone, with an ocean full of fascinating animal species between us. In late November the researcher and writer will return to the city at the banks of the river that gave him his name to talk about animals, animals, and even more animals in a packed hall at De Vereeniging.

Silverback

But, back to those apes at the Psychology department. One night they escaped. After partying for a while in the abandoned building, they crawled back into their cages, and closed the door, leaving no traces of their escapade. The next morning found them lying innocently in their straw beds. The only thing was that they had forgotten to clean up their droppings in the corridor. The secretary discovered the droppings and snitched on the cunning chimps. ‘Are apes able to think ahead?’ asked a senior researcher to De Waal while nursing his pipe. After all, the animals had carefully closed their cages so that it would look as if they had never left them.

This was quite the revolutionary perspective at the time. Animals were still mostly seen as stupid creatures, driven by instinct alone. Anyone who suggested that they might experience emotions or make plans was ridiculed as unscientific. A few rare exceptions – including the pipe-smoking researcher – did dare to make such suggestions. Frans de Waal would later grow into being the silverback of researchers championing the ‘animals are smarter than you think’ approach.

His own studies in biology paved the way for his future career. He once heard a professor explain the zigzag dance of the ‘three-spined stickleback’, one of his favourite childhood animals. In his book he writes about this incident: “It was the first time that I realised that watching how animals behave, which was the thing I liked to do most, could actually become my profession.”

He classifies the Nijmegen degree programme retroactively as ‘good and solid’, but he missed working with living animals. ‘There was very little of that. Instead, we did many practical experiments with dead animals in formaldehyde – which stank terribly.’

So after his first-year exam De Waal left his student room at the Mariënburg, waved his Quo Vadis friends good-bye, and left for the North. ‘In Groningen they had an entire study programme on ethology (behavioural biology).’

They also had jackdaws, another favourite childhood animal – he had kept some as pets when living in Brabant with his five brothers and sisters. University researchers were studying the birds’ behaviour. De Waal took two home. During the day he would leave the windows of his student room open so that the birds could fly in and out. At night, he put them in a cage. One day they failed to return. He was glad they had reclaimed their freedom. ‘I think they probably made it’, he says. ‘They were used to living in the wild.’

Ten thousand hours

He also took off, and went to Utrecht. He completed his dissertation under Jan van Hooff, the great primatologist who had grown up between the aardvarks and orang-utans of Burgers’ Zoo – his father was the zoo director. And so De Waal made looking at animals his profession. He estimates that he must have stared at chimpanzees for at least ten thousand hours. ‘We didn’t have screens yet. I was at Burgers’ Zoo on the other side of the canal, and the apes were on their island. There was also an indoors space from which we could see the animals.’

In Arnhem, De Waal laid the foundation for his career. He discovered that chimpanzees patch things up after a conflict. It looked suspiciously like people’s behaviour after a fight. His results were scorned. Forty years down the line, his work is received quite differently. De Waal is a popular speaker; his books are all bestsellers and enjoy even more fame in America and Japan than in the Netherlands.

You often appear in the media. What message do you wish to convey?

‘What I want is for philosophers, anthropologists and psychologists to take into account the fact that we are also just animals. We have this tendency to think that humans are somehow different, that we stand apart from the rest. This is the kind of thinking I try to counter as a biologist. Humans have a number of remarkable characteristics, but none of them are so unique as to make us into something else than animals. In my book I write: ‘Human cognition is nothing but a variation on animal cognition’.’

Trunk

De Waal shows that animals experience emotions just as we do in a multitude of studies. Elephants comfort one another with their trunks, and voles can display empathy. The primatologist no longer limits himself to apes. In Are We Smart Enough to Know How Smart Animals Are? he describes the art of good research into animal behaviour. Researchers thought that chimpanzees were unable to recognise faces for years. Humans were supposedly much better at it. Until one of De Waal’s students in Atlanta ran an experiment in which the apes were not asked to recognise human faces, but instead were shown photographs of other apes on a computer screen. It turns out they were just as good at face recognition as we are.

Another example: an elephant was supposedly not smart enough to recognise itself in the mirror. Until one of De Waal’s student had the brilliant idea of replacing the mirrors with much larger ones, nearly three square metres in size. Suddenly, Asian elephant Happy at in a New York zoo had no trouble recognising herself in a mirror: there was a white cross on her forehead and when she saw it in the mirror she started to rub it off.

‘The challenge is to find tests that match the temperament, attention span, anatomy and sensory capacities of a specific animal’, says De Waal.

What is the answer to the question in the title of your latest book? Are we smart enough to know how smart animals are?

‘I am optimistic. I think that we are smart enough to find out a lot of things about animals. There is a new generation of animal researchers who think outside the old-fashioned box that states ‘animals are only driven by instinct’ and ‘they are only capable of learned behaviour’. Our thinking about the intelligence of animals has changed dramatically over the past one hundred years.’

Which animal do you think is the most intelligent?

‘Now that’s actually a very difficult question to answer, because every animal has the intelligence required to live the way it lives and to do what it does. It’s hard to compare an elephant with a primate, or a primate with a dolphin. These animals are so different, even though they are all mammals.’

‘I currently lead a kind of double life’

Is a squirrel less intelligent than a human because it cannot count to ten? The life of a squirrel does not require counting. It is however essential for a squirrel to be able to find the nuts it has hidden when it gets hungry. Clark’s nutcracker, a bird, is even better at it. Every autumn it collects more than twenty thousand pine nuts, spread over four hundred locations in an area of a few square kilometres. And it finds nearly all of them. That’s a performance humans would certainly have trouble matching. “I even sometimes forget where I parked my car,” writes De Waal in his latest best-seller. In other words: measuring cognition along a single dimension is a pointless exercise.

Since 2014 you are not only a Professor in Atlanta, but you also hold a chair in Utrecht. Will you return to the Netherlands one day?

‘No, we are staying in Atlanta. I currently lead a kind of double life, because I also have an apartment in Utrecht, where I teach summer schools. I also teach in Atlanta, although I have reduced my research team here. I am still involved in a number of projects. One in Arnhem, one in Africa and one in a hospital in Atlanta – the latter of which is a study on human behaviour.’

Having spent a lifetime studying animals you are now observing human behaviour?

‘Yes. I observe people in the operation theatres of Emory Hospital, the largest hospital in the Southern US. They perform operations all day long and just as in the Netherlands, conflicts sometimes arise between surgeons, anaesthetists, assistants and nurses. Instead of asking people what happened and getting unreliable answers, we sit in the room with an iPad and make notes. Just as we do with chimpanzees.’

And? What are your conclusions?

‘It’s too early to say. We are just now concluding the study.’

On Tuesday 29 November Frans de Waal is giving a lecture in concert hall De Vereeniging in Nijmegen. Tickets cost € 10 (€ 5 for students and staff). You can reserve your seat via ru.nl/radboudreflects.