Protector of the Night Watch

-

Photo's: Duncan de Fey

Photo's: Duncan de Fey

The Night Watch runs like a thread through the life of Pieter Roelofs, Head of Paintings and Sculpture at the Rijksmuseum. He’s closely involved in the masterpiece’s restoration, due to start this summer. He studied Art History in Nijmegen.

‘Look here.’ Pieter Roelofs points to something on the Night Watch. The last visitor was swallowed by the Amsterdam city centre two hours ago, and a deep silence hangs over the Gallery of Honour of the Rijksmuseum. Followed by the VOX journalist and photographer, Roelofs, Head of Paintings and Sculpture at the Rijksmuseum, makes his way through the museum’s white-plastered hallways, up the deserted staircases, all the way to Rembrandt’s most illustrious painting. A passing guard nods to Roelofs and disappears into the empty museum.

‘Come a little closer’, says Roelofs, as he steps across the tightly stretched cord. Just a moment ago, he was telling us how skilful Rembrandt van Rijn was in guiding the viewer’s gaze. In this case towards the hand of Captain Frans Banninck Cocq, the shadow of which falls precisely on his lieutenant’s coat. And lo and behold, between the shadow’s thumb and index, the coat is embroidered with the Coat of Arms of Amsterdam.

Theatrical production

This is the most exquisite element of the Night Watch, says Roelofs, because it expresses precisely what the painting is all about: the militia of Amsterdam protecting its citizens against intruders, at the time the Spaniards.

From a historical perspective, this is a unique phenomenon: across the world, it was the nobility rather than the common people who were responsible for protecting city and land. What’s more, Rembrandt doesn’t portray his marksmen in neat rows, easily recognisable and brightly coloured. ‘He does something completely unusual that distinguishes him from all his contemporaries. Rembrandt doesn’t focus on people, but on the action. He’s putting together a theatrical production. He paints the militia as they march out; the lines of the weapons held by the men suggest movement. He creates depth and tension with muted colours in the background and bright colours in the foreground. He uses every single art theoretical tool at his disposal to tell a story.’

‘We feel responsible for passing the painting on to our grand-children in mint condition’

The Night Watch hangs in the best spot in the museum. In 1885, architect Pierre Cuypers designed the Rijksmuseum as a cathedral to art, with the Night Watch in place of honour on the high altar. And this is where it’s hung pretty much ever since. Only twice did the painting slide down the giant letterbox, unobtrusively positioned just below it, into the passage outside: once during World War II, and once in preparation for a major renovation in 2003.

White haze

This summer the painting is due to be restored, for the 26th time in four centuries. A white haze has developed around the little dog. Vague patches have appeared in Banninck Cocq’s clothing. There are signs of wear and tear here and there. The times when the painting was attacked with knife or acid have left their traces, and the over-painting is starting to show through. ‘Nothing dramatic, just small things we want to understand and address. We feel responsible for passing the painting on to our children and grand-children in mint condition. That’s why we decided that now is the time to use all the technology and expertise at our disposal, and to join forces with restorers, researchers and curators.’

This led to a detailed analysis of the painting’s current state, following which the experts formulated a treatment plan. The Night Watch will be taken down from the wall and out of its frame, and stretched onto an easel created especially for the occasion. A platform lift will accommodate the state-of-the-art research equipment used by the experts to examine all the individual paint layers: from varnish and top layer all the way to the canvas. ‘We get to see something that was never meant to be seen. We can follow all of Rembrandt’s thought processes on the canvas.’ And not only those of the master painter. Rembrandt was a company. He worked with pupils, many of whom contributed to the final product. ‘By studying the painting this closely, we may be able to distinguish differences in hand.’ The public is invited to follow the restorers’ progress via a glass wall (and online). Not a day will go by when the Night Watch will not be visible.

Fun

Pieter Roelofs was ten years old when he first stood up in public to talk about Rembrandt. The place: his primary school in Druten. Following that first school presentation, Roelofs never entirely freed himself from the 17th century master. He visited museums, including the Rijksmuseum, with his little sister. Their parents took them ‘because they could see we thought museums were really fun’.

Roelofs went on to study Art History at Radboud University, and at the age of 19, found himself once again in front of the Night Watch. He can remember the moment precisely, as the painting became the subject of a heated discussion between his professor, Christian Tümpel, and Art Historian Egbert Haverkamp Begemann. ‘Right there and then, something amazing happened between these two men.’ Listening to them talking, Roelofs the student suddenly understood the profound significance of the Night Watch for Dutch art. ‘There are moments in life you know you’ll remember forever, and for me, that was such a moment.’

‘The entire world comes together here’

As a student, he specialised in 17th century Dutch art. ‘We had a very active student club at the Department of Art History. We launched an art historical magazine, Desipientia, and the fun thing is it still exists.’ After a short stint as researcher, Roelofs worked for three years as curator at Museum Het Valkhof, where he was responsible, among other things, for organising an exhibition entitled ‘Brothers of Limburg: Masters at the French Court’. It was a great hit. He’s worked for the Rijksmuseum for thirteen years now. To him, the second floor, with its masterpieces from the Golden Age, is like one big candy store.

Catherine the Great

Roelofs leads his visitors past portraits of rich burghers in white ruffs, paintings of sea battle victories, Delft Blue china, and dollhouses used by the rich to copy the interior design of their own houses. It’s actually a bit of a miracle that the Netherlands has such a large collection of 17th century paintings, explains Roelofs as we walk. In the Golden Age, the Netherlands produced six to ten million paintings, but the large majority disappeared abroad just a century later. ‘Catherine the Great shipped masses of paintings to Saint-Petersburg, and industrialists took some to America. When we started collecting paintings for the new Rijksmuseum building in 1885, the market had been pretty much skimmed.’

Long Live Rembrandt

Rembrandt is hot, as apparent from the viewer figures of Project Rembrandt, an amateur painting competition that’s been broadcast on Dutch TV over the past months in honour of the Rembrandt Year (the painter died 350 years ago). Roelofs was one of the two permanent jury members.

In the programme’s wake, the Rijksmuseum is due to open an exhibition entitled ‘Long Live Rembrandt’, showcasing six hundred artworks by amateurs – all inspired by Rembrandt. Roelofs personally reviewed photographs of all 9000 submissions. Projects such as these fit in perfectly with his mission: to make it clear that art is by and for everyone. ‘We’re constantly thinking of ways to make the museum more relevant and more open.’

Swapping is the way museums have found to temporarily expand their collections for exhibitions. ‘I loan you something, then you loan me something back.’ With its top collection, the Rijksmuseum is in a strong negotiation position. ‘Which we use to benefit the Netherlands Collection’, Roelofs is quick to add. ‘We are now sending one of our pieces to Berlin, in exchange for which the Museum Prinsenhof Delft can borrow a painting. We often do this. We find it important for culture to be visible and widely accessible across the Netherlands.’

Champions League

Roelofs and his colleagues are always on the look-out for new art: an undiscovered Jan Steen or a Rembrandt from a private collection that becomes available. The museums are in contact with collectors and rich families, like the Rothschilds, who own paintings by the great masters. Whenever something becomes available, players like the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the National Gallery of Art in Washington are quick to pounce. He laughs: ‘At times, it’s like the Champions League.’

Trained eyes are the tool of his trade. If a painting has been overpainted, Roelofs can see it. ‘You can see it for example when you look at the layers. If paint was added later on, the background doesn’t shine through the top layer anymore.’ But he doesn’t exclude the possibility that his eyes might betray him. Two years ago, a colleague from the Louvre almost bought a Frans Hals, but it turned out to be forged. ‘It makes you think: with our current technology, how can we still fall for it? Art forgery is of all times, so I can’t guarantee that there isn’t a single fake among the seven thousand paintings of the Rijksmuseum. But we do systematically and regularly put our entire collection to the test using the newest technologies.’ The Louvre discovered 20th century pigment fragments in the painting’s first layer.

‘Papa, is there a Playmobil version of these people?’

Roelofs still lives in Nijmegen. And he’s proud of it too. ‘Surely I’m allowed a bit of local chauvinism, no? I feel I’m an ambassador for Nijmegen.’ The exhibition organised 18 months ago on the mediaeval painter Johan Maelwael, who came from Nijmegen, was Roelofs’ idea. And it’s thanks to him that the painting by Albert Cuyp entitled River Landscape with Horsemen, with a view of the polder near Nijmegen, now hangs in a beautiful spot in the Gallery of Honour. As his visitors stare in wonder at the landscape, he smiles. ‘The painter’s pumped up the moraine to make the scene more romantic and dramatic. And do you see this golden yellow in the background? He’s added Italian light. This is what 17th century painters like to do: manipulate the viewer.’

Back in the 17th century, Nijmegen was a top location, says Roelofs. ‘Half the Rembrandt School were there, maybe even Rembrandt himself. It was a remarkable, atypical slice of Dutch landscape. The Valkhof also made a deep impression on artists, as one of the largest castles in the Low Countries.’

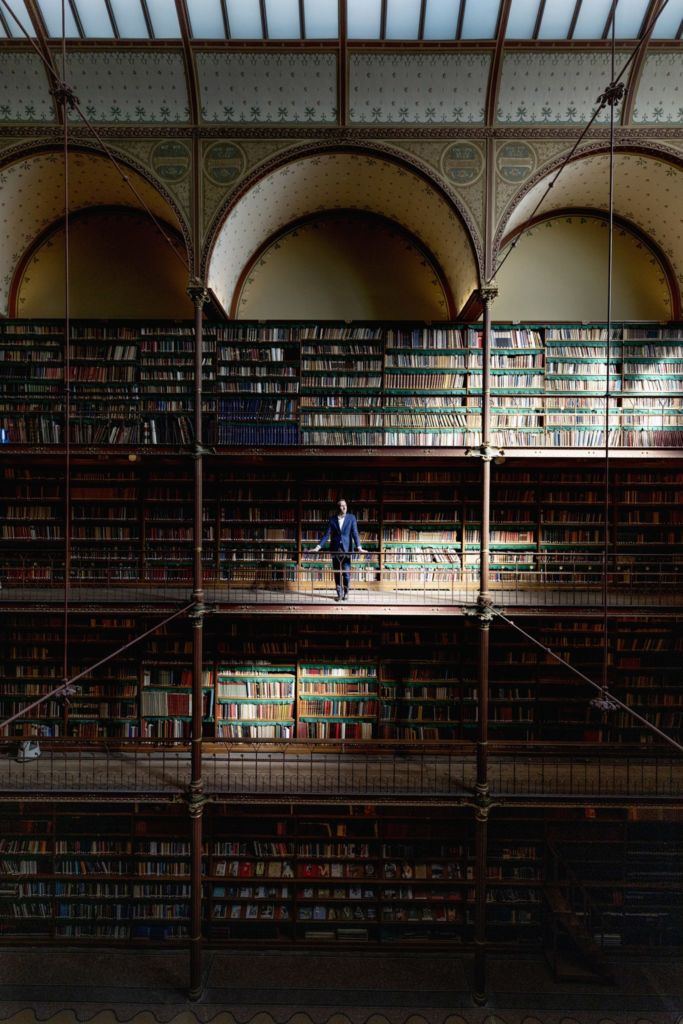

Did we know, by the way, that Nijmegen also has a kind of Rijksmuseum? The old Canisius College on the Berg en Dalseweg looks very much like the Rijksmuseum in terms of its design. It was built by Nicolaas Molenaar, a pupil of Cuypers, and contains a miniature version of the Rijksmuseum’s magnificent library. Just something Roelofs thought he’d mention in passing.

Back to the Night Watch. Does he still look at the famous militia portrait every day? “I try to come as often as I can, and listen to what people are saying as they stand here. The entire world comes together here; there’s a kind of energy hub.”

‘Papa’, asked Roelofs’ then five-year old son as they stood looking at the Night Watch, ‘is there a Playmobil version of these people?’ Roelofs suggested the idea to his colleagues, six or seven years ago, assuming no one would be interested. ‘But they were all enthusiastic.’ Now, when he’s at the Metropolitan Museum for work, and happens to see a Playmobil version of Captain Frans Banninck Cocq and his lieutenant at the museum store, he’s reminded of how small things can start.