Summer interview (2): storm chaser Margot Ribberink

-

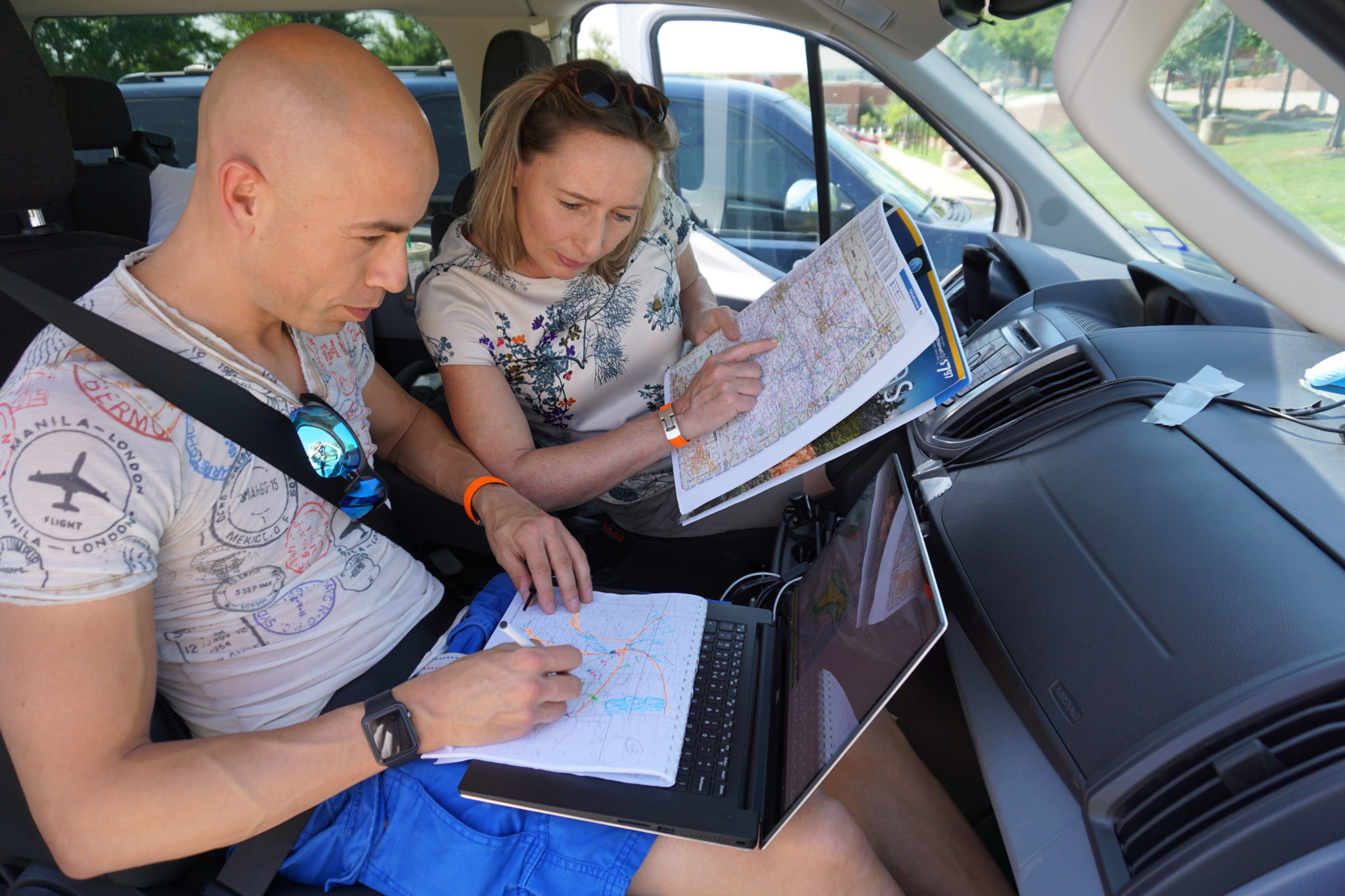

Margot Ribberink in Texas. Photo: Annemarie Haverkamp

Margot Ribberink in Texas. Photo: Annemarie Haverkamp

Tornado hunting: that is the remarkable passion of the Nijmegen weatherwoman and former biology student Margot Ribberink (52). And she’s not just doing it for kicks. With the Texas storms on her heels, she explains that tornadoes are becoming increasingly more frequent. The cause: climate change.

Outside, the siren is sounding. On the radio, a computer voice warns: ‘This is a tornado alarm. Seek shelter immediately.’ Our hired Ford van races over the road. Not away from the threatening clouds, but right towards the storm. ‘This might just turn into one,’ exclaims Margot Ribberink excitedly from the back-seat. Her eyes are scanning the horizon. ‘Keep looking, guys! If you don’t look, you won’t see anything.’

‘Scientists still don’t know why a tornado develops in some cases and not in others’

A statement worthy of Johan Cruijff, she admits, but she means what she says. In tornado hunting, her greatest passion, you can sometimes make the mistake of focusing too much on the computer screen. If you concentrate exclusively on the constant stream of weather data, you can completely forget to look up. And, as a result, miss the magical moment when a devastating trunk appears below the swirl of dark clouds.

We are driving at high speed through Texas. This is tornado country. Every year, the dreaded whirlwinds claim dozens of US victims. At speeds of hundreds of kilometres per hour, the tornadoes rush over the vast country, dragging houses, trucks, cows and people in their wake. To escape these natural disasters, most people dig a shelter next to their house.

But Ribberink does not seek cover. Together with her team of Dutch meteorologists, she jumps out as soon as the van stops, camera in hand. There is an air of excitement. Is it going to happen? The weatherwoman explains that what we see is a supercell, a thunderstorm of the heaviest kind. The odds are 10 to 1 that this ‘monster’ will give birth to a tornado. ‘Scientists still don’t know why a tornado develops in some cases and not in others. It probably has to do with the difference in temperature between the warm rising air flow and the cold air sinking towards the ground from the cloud.’

But no matter how apocalyptically the dark clouds are spinning, we will not see a tornado today. We have to get back in the car, as waiting for a thunderstorm to hit you is extremely dangerous. The weather radio station warns against the hailstones we already hear bouncing off the roof. The accompanying lightning flashes may well hit us. The trick is to follow a storm and watch it from as close as possible, but in such a way that you can quickly get away in your van. On one of these chases, Team Ribberink covers an average of eight hundred kilometres per day.

A gift

It’s her hobby. Nearly every year, the Nijmegen weatherwoman – she was the first weatherwoman on Dutch TV and later became famous with her weather reports for RTL4 – takes three weeks off from her job at MeteoGroup to chase the utmost extreme weather at her own expenses. This year, tornadoes abound in the US: already more than one thousand were observed. In other years, this represents the total at the end of a whole season (from March until August). Bad news for the citizens, but a gift for the storm chasers.

What’s so exciting about this cloud-chasing on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean? ‘Extreme weather such as this is much rarer in the Netherlands,’ explains Ribberink. ‘These skies are so imposing. And very instructive. On the way we formulate our own predictions based on observations and radar images. We follow our own scenario, even if the weather reports say something else. It’s so exciting when we get it right! As meteorologists, that really gives us the feeling that we understand the atmosphere.’

The birth of a tornado

A tornado occurs when cold and warm air meet. The two don’t mix, but form a demarcation line along which the air swiftly rises. This can grow into a thunderstorm. If there is enough wind shear (large difference in wind speed or direction above and below in the atmosphere), a supercell can form. The rising warm air causes an air deficit close to the ground (a small low pressure area) that is replenished from below. If this air flow condenses all the way down to the ground, we speak of a tornado. Dangerous tornadoes are between twenty metres and a few kilometres wide (on the ground) and can reach a speed of 150 to 450 kilometres per hour. They usually cover a few kilometres.

Of course she takes care to not cheer in public when she sees a tornado – that’s something the Dutch meteorologists do in the privacy of their Ford van. Because the damage for the inhabitants can be severe: from lost harvests to devastated villages, not to mention deaths. Ribberink wants to use the knowledge she acquires in Tornado Alley, roughly the area between Mexico and Texas, in the Netherlands. ‘The better we understand how this kind of dangerous weather occurs, the better we can warn people about it. On 23 June of last year in Brabant, there were ten-centimetre wide hailstones: nothing like that had ever happened before. We will also increasingly have to deal with this kind of extreme weather.’

The cause: global warming. Ribberink has been warning people about the consequences of climate change for over twenty years. ‘I read book after book on the topic; I knew so much! At some point I thought: I have to do more than simply present the weather report. I have to make people realise that we are heading in the wrong direction. The first step is sharing knowledge.’

Climate commissioner

This kind of knowledge tends to be lacking in the part of America we are now driving through. Most people here are uneducated and poor. Sixteen percent of Texans live below the poverty line (an annual income of less than €22,000 for a four-person household). Along the road we see trailer parks and junkyards. And signs announcing gun shows.

We stop in a desolate-looking village. Most of the shops are vacant, a small dog is crawling over the hot asphalt. ‘Hey, I’d rather not see the likes of you around here,’ jokes a fat woman, pointing at the tornado stickers on the side of our van. Tornado chasers in your street spells out trouble: bad weather is on its way. Then she tells us her own tornado story. How she once saw four tornadoes in one day. How her son was lifted up in the air, only to be dropped back down (luckily still alive) further on. No, she is not going to watch it; she’d rather hide deep in her cellar.

‘America is one of the key players’

The irony is that it is Texas of all places that voted for Trump, the man who denies the cause of the natural disasters that so often hit people here. Not only that, he is even taking down websites that offer scientific evidence of climate change, and is planning to stop funding the largest climate research centre in the US, the National Weather Center in Oklahoma (where we plan to make a tourist stop the next day). Trump prefers to spend his money on space and defence programmes.

‘This is truly very alarming,’ says Ribberink. ‘This centre creates overviews of temperatures across the world. They register extremes – forest fires and floods – so you can see how fast the Earth is warming up. All over the world meteorologists make use of their data. Everyone knows it. The knowledge they produce is essential.’

The fact that the controversial president recently pulled the plug on the Paris Climate Agreement is a historical disaster, she says. ‘America is one of the key players.’

Although on her travels through America, Ribberink feels no need to play climate commissioner – where do you start? – But in the Netherlands, this occupies most of her time. She gives lectures and provides information and is one of the driving forces behind Nijmegen Green Capital; in 2018 the City on the Waal River can call itself the most sustainable European City.

‘In the Netherlands we also notice the effects of climate change, but in other parts of the world, the situation is much more drastic. The famine raging through the Horn of Africa has everything to do with the climate. If we want to stop the Earth warming up by more than two degrees, as was agreed in Paris, we have to quickly and dramatically reduce our CO2 emissions. I like to show people that they themselves can do something about it.’

In order to chase tornadoes, you fly to the US and drive thousands of kilometres in a diesel van. Speaking of CO2 emissions…

‘Yes, this is a dilemma I’m fully aware of it. At home I try to compensate, for instance by planting trees via Trees for All. But it would be better if I didn’t fly. The problem is that that would also mean not being able to garner this knowledge.’

Crying

The next morning at our motel we see on TV ‘our’ storm, the thundercloud we chased all the way to Oklahoma. Hailstones as big as baseballs fell out of the sky, the towns’ streets were covered in white. ‘You’re really lucky,’ says Ribberink as she sips weak coffee from a plastic cup. ‘The circumstances are once again favourable. We may be able to see a tornado today. You could just as easily have had two days of bad weather.’ By ‘bad weather’ the tornado chaser means blue skies and sunshine – sounds awful indeed!

After a short briefing in the breakfast room we are off once again. Deeper into Oklahoma. Promising thunderstorms are expected there later today.

Ribberink tells us how she joined the Dutch team, whose members change every year, for the first time in 2004. Her children were still young. ‘What is your mother going to do?’ asked the teacher when her youngest, aged 8, proudly announced that mamma was going storm chasing. At home it was a non-issue. Her husband doesn’t mind her passion and her daughters – both of whom are now studying at Radboud University – thought it was cool. ‘We all want to come home in one piece,’ says Ribberink as she looks around the van. And yet, things can get quite uncomfortable. In 2013, three American storm chasers were killed by a tornado. Including a devoted father and son. ‘I knew them. They were very experienced and certainly not reckless. It makes you think: should we really be doing this? It could go wrong any day.’

But adventure beckons. The first three years that she joined the team, her patience was really put to the test. Not a single tornado in sight. ‘When I finally saw my first one, I cried’, she remembers. This was also due to the men teasing her, blaming her, as the first woman on the team, for the bad luck they had those three years. Ribberink may look tough, but she also has a vulnerable side. As a child she had little self-confidence and was shy. This led her to the wrong choice of study programme: she went to study biology in Leiden because two of her Twente friends were going there too. They were supposed to share a house, a very safe proposition. ‘After two weeks I hardly saw them anymore; they just went their own way. I didn’t get along with the Leiden students at all, and felt deeply unhappy. After six months, I went back to Hengelo.’

She got a second chance in Nijmegen. Ribberink ended up at the Galgenveld and immediately felt at home with the other students on her floor. ‘We did everything together. Late nights at De Fuik, Dio and the HBO association [now Merleyn, Eds.]. I had a great time there!’

Suits

While she talks, Ribberink taps on the window in the direction of the clouds above us. ‘Look! That cauliflower is growing nicely.’ And ‘There, mammatus clouds, also known as udder clouds – those are rare in the Netherlands.’

She’s always had a fascination for the weather, but it was only after graduation that she decided to do something about it. She applied for a job at the newly formed Meteo Consult, a rival of the KNMI, and was accepted. She retrained herself from plant ecologist to meteorologist and underwent a physical transformation as well. ‘I looked like a biologist. I had a long braid and wore overalls. They told me there was no way I could appear on TV dressed like that.’ Ribberink was sent to the hairdresser and fitted with suits. She found the result so horrifying that for two years she did not dare to look in the mirror. Once again her shyness prevented her from saying anything about it. It was only later that she developed her own TV look. Now she present the weather report at Max Broadcasting or Gelderland Broadcasting sometimes even while wearing jeans. ‘Nice jeans, mind you, but when I coach other weatherwomen, I always tell them to stay true to themselves.’

On the horizon the yellow stripes have now turned into threatening sky. Team member Arno shows us his laptop. ‘You see this blue pit?’ A broad grin. The blue pit on the radar is a hellish thunderstorm very close to where we are. We are at the right spot! The road fills with the pick-up trucks of other tornado chasers, some with impressive satellite dishes in the back. We get out in the ditch as the wind pulls on our clothes. The supercell sways like a spaceship above the land and has a swirl at the bottom. But the cold air ruins it all. No trunk appears, and we have no choice but to go in search of a new thunderstorm.

Afterword: On this trip, the team ended up seeing five tornadoes (the reporter was back in Nijmegen by then). Photographs and videos can be found on the Facebook page of Tornadojagers.nl.