Survey shows internationals feeling less welcome in the Netherlands: ‘This will take decades to fix’

-

Biking lessons for international students during the orientation week. Photo by Johannes Fiebig

Biking lessons for international students during the orientation week. Photo by Johannes Fiebig

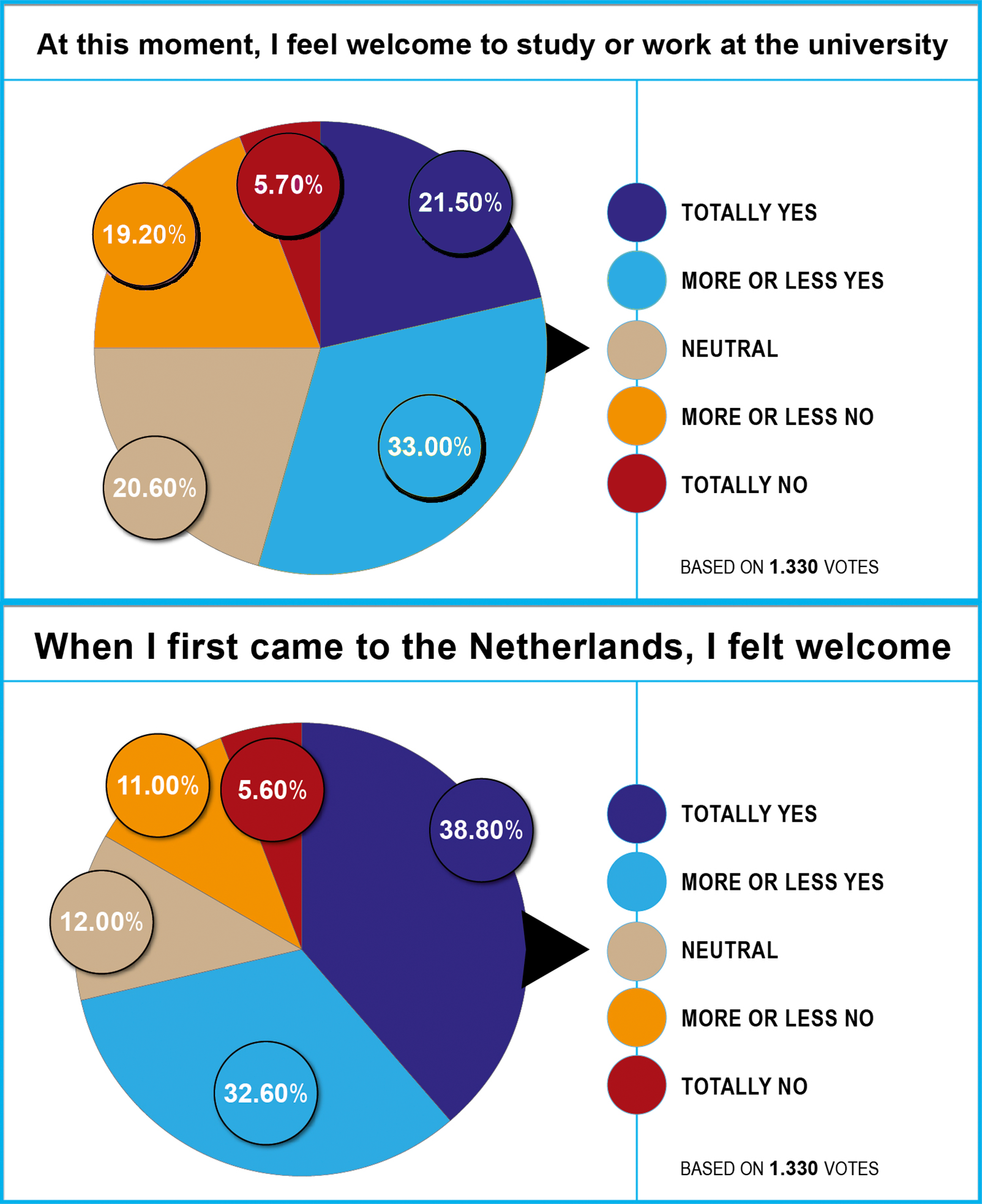

Internationalisation in higher education has been a hot topic of discussion for months leading up to the election. But how do international students and staff members feel at university right now? Less welcome, as a survey by seven university magazines including Vox, shows.

The answer of the 1.330 international survey respondents from Nijmegen, Groningen, Twente, Utrecht, Delft, and Wageningen is clear: international students and staff all over the Netherlands feel less welcome now than when they first arrived in the country. At the moment, a quarter of Nijmegen respondents do not feel welcome at the university.

On initiative from the Ukrant, the independent magazine of the University of Groningen, and in collaboration with other independent Dutch university magazines from all over the country, Vox conducted a survey on international wellbeing leading up to the elections. At Radboud University, 264 international students and staff members completed the questionnaire.

Politics

After the Dutch minister of education, Robbert Dijkgraaf, called for a hold on international marketing and recruitment activities earlier this year, internationalisation at Dutch universities has been widely discussed in party platforms and debates in the lead-up to this year’s election.

One of the debate’s most prominent voices, Pieter Omtzigt, has thereby called for a radical reduction of English-taught courses in Dutch higher education and has criticized the number of international people currently studying and teaching at universities in the Netherlands. Omtzigt’s party, New Social Contract, is up for election for the first time this year.

‘The country has invested decades in improving internationalization policies and they want to erase them with the stroke of a pen,’ writes one Spanish academic staff member. ‘This is a terrible mistake; the Netherlands needs internationals. The current policies in place will cause a setback that will take decades to fix.’ One staff member at the Faculty of Philosophy, Theology and Religious Studies called the current political developments an ‘academic suicide.’

‘I think the Netherlands have been proud to be a progressive and open country for many decades, and it’s one of the beautiful things about them,’ writes a German international. ‘Restricting English education is trying to push back on their own core values and culture, and I think that even if it is decided, it will just take a few years until it will be reversed again.’

Leaving

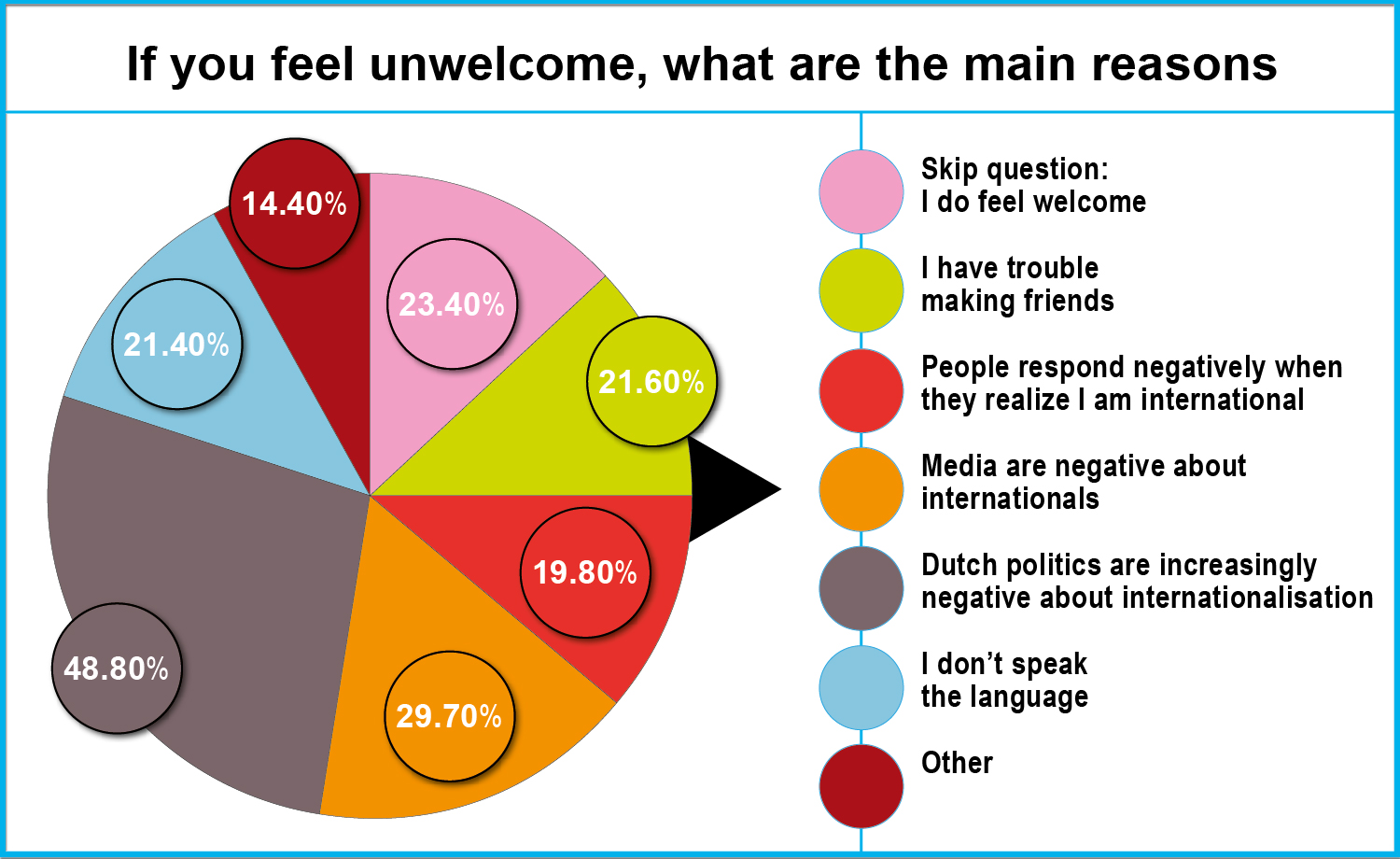

When asked about why they feel unwelcome, negative attitudes by politicians were the second-highest reason among Nijmegen based respondents. Politics was only surpassed by not speaking Dutch well enough: almost a quarter of responses identified language as a reason for feeling unwelcome.

‘This [debate] in combination with the ongoing Zwarte Piet traditions makes me very concerned about staying here and – more importantly – raising my kids here. They will inherently be multi-national and -cultural and I’m extremely concerned about their safety here if this continues,’ one respondent from the Faculty of Social Sciences writes.

‘I would not want to spend a day of my life working and contributing to an economy and society that does not make me feel wanted, let alone included or appreciated,’ writes one master’s student from the Nijmegen School of Management. ‘The increasing difficulty and blatant racism and xenophobia internationals may face while looking for housing does not fill me with optimism for the future,’ writes another international.

Right now, around 24 per cent of Nijmegen respondents state that they are thinking about leaving the Netherlands, around 20 per cent are unsure. 29 per cent worry about their position at Radboud University – especially students and staff from outside of Europe.

Language

Compared to other universities, Nijmegen students and staff members were the least likely to speak Dutch. More than half answered that they do not speak the language. At the same time, the higher the career stage of the respondents, the more likely they were to speak Dutch. While only 38 per cent of bachelor students stated that they speak Dutch, almost 69 per cent of academic staff and 58 per cent of PhDs and postdocs said that they speak the language.

What also becomes clear: internationals in Nijmegen are willing to learn the language. Of the respondents who don’t already speak the language, 57 per cent stated that would like to learn Dutch, 36 per cent answered with ‘maybe.’ Amongst Nijmegen internationals, there is a small trend towards respondents who are more fluent in Dutch currently feeling more welcome, less worried about their position and are thinking less about leaving.

‘As international students, we choose a particular country to study in consciously, hence, we are prepared to learn a new language and culture,’ writes a Polish bachelor student. A master’s student from the Faculty of Science writes: ‘I have talked to people and they all say they do not agree with the discourse and think that especially people like me (who want to integrate and learn the language) should be welcome to stay here.’

Future

PhDs and Postdocs in Nijmegen feel generally more enthusiastic about working and studying in the Netherlands than other groups at Radboud. Additionally, students at the Faculty of Science and the Faculty of Social Sciences would recommend studying in the Netherlands much more than students from the Faculties of Management and Arts, Philosophy, Theology, and Religious Studies. Overall, more than half of the respondents would still recommend studying or working in the Netherlands. Many stress the high level of education as a positive when talking about their experience at Radboud. ‘I consider the Netherlands as home,’ writes one Iranian respondent.

The results of the survey come just after the university announced a further decrease in international enrolment at Radboud in its annual October numbers report. Starting next year, the university has also announced that it would not support international bachelor students in finding housing anymore, instead focussing housing support on master’s students. This decision had led to criticism earlier this year.

Due to the open and anonymous nature of the survey, as well as the total number of respondents, the survey’s results should be interpreted as indicative. The results give an insight into international sentiments at Radboud University, as well as at other Dutch universities.

With thanks to Stan van Pelt for the statistical analysis of this survey.