Precedent

-

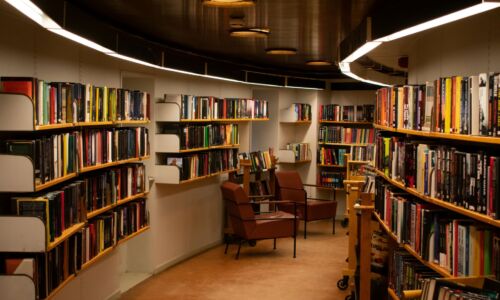

Antonia Leise. Foto: Dick van Aalst

Antonia Leise. Foto: Dick van Aalst

‘You know what I don’t understand?’, someone said during my final history lecture of the last semester. ‘Why they are asking everyone, from ethicists to economists to epidemiologists, but not a single historian about this.’ This being the vaccine mandate. The discussion about it had arisen during the final lecture’s coffee break before the Christmas holidays. Or rather, the last one before the remaining courses of 2021 were moved online because of the Christmas-lockdown.

One lockdown, one semi-lifted half-lockdown and a booster shot later, we have arrived at the following stage: the restrictions are lifted! Set the masks on fire (unless you want to take a bus); spit into each other’s mouths if that floats your boat; we have made it to the final press conference! Corona is over! Well, in the Netherlands. Not in Germany. A bit in Britain, depending on whom you’re asking. But here, absolutely. Starting on the 25th of February.

Amidst this great news, the question of a vaccine mandate has somehow disappeared. Not that it was ever a real discussion in a country where people already start lighting small cars on fire if someone just dares to utter the word avondklok. A possible decision to implement a vaccine mandate? Not on anyone’s bingo card for the near future. The ethical implications would just be too severe. A vaccine mandate could, in the end, be a dangerous precedent. Or could it?

The answer someone gave to this question is what stuck with me after the coffee break before Christmas: ‘We had a vaccination mandate in the Netherlands until 1975 – for the smallpox,’ they said. And the Netherlands were not the only country: Germany had a vaccination mandate for smallpox until 1976 and 1982 in the west and east respectively, Austria until 1981. It’s easy to forget, over the course of roughly 40 years. But while a vaccination mandate can obviously still be discussed (and has been extensively in the past), a precedent, it is not.

But alas, the vaccination mandate conversation was not one led by historians. It belonged to ethicists and medical professionals. It was a debate with questions about bodily autonomy at its centre and weightings of individual freedom versus public safety. None of those questions are bad. They’re actually really good questions; people write entire books about how difficult it is to answer them. But just for a second, I wish there would have been a mutual understanding that this is not merely a debate of a hypothetical, but one we have had before. One with a different outcome in the past. And one, whose outcome this time has had deadly consequences – and lockdown or not, will continue to do so in the future.

Read Antonia Leise's blogs here