A 97 million euro mega-grant is not a lump sum

-

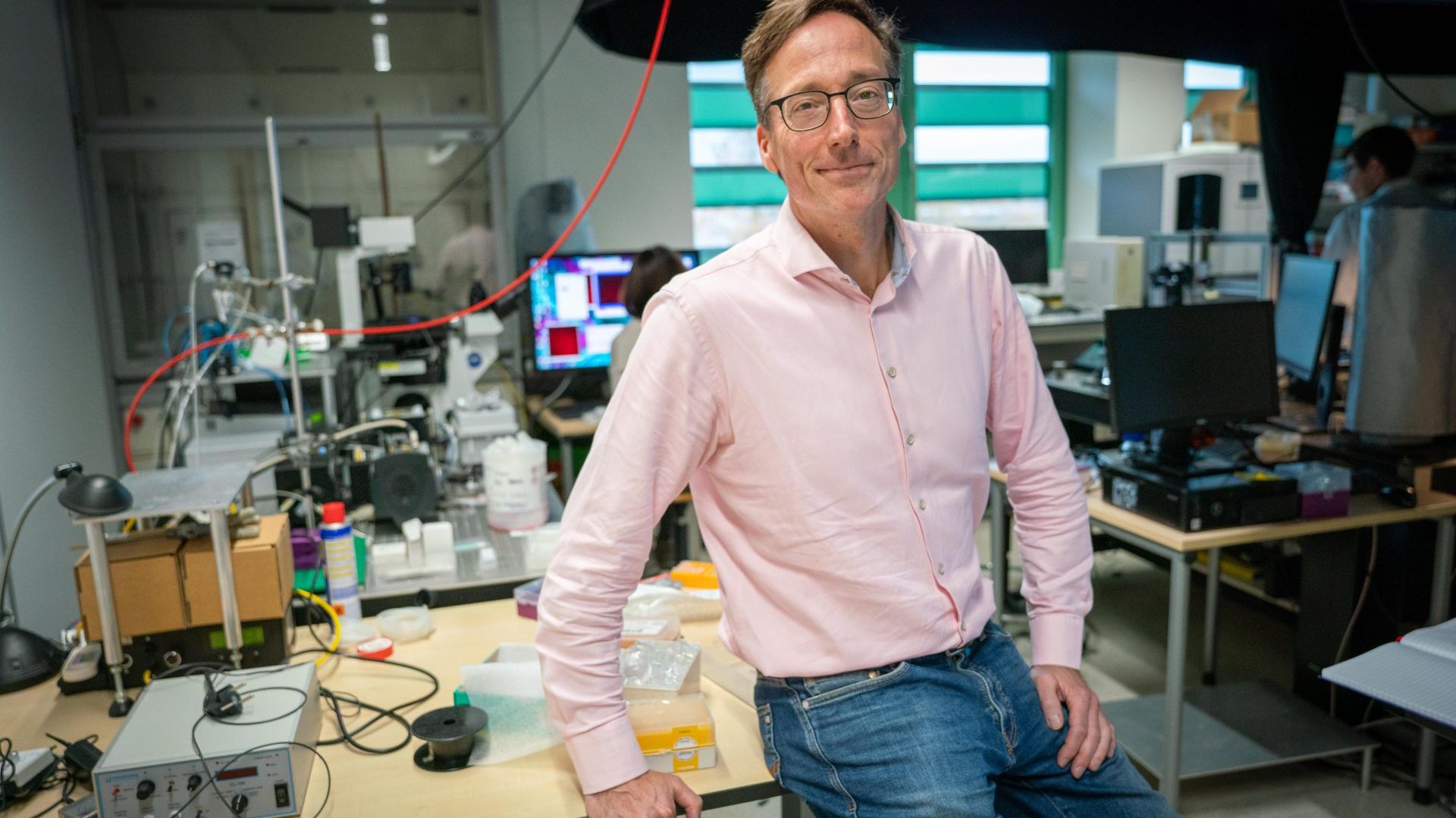

Wilhelm Huck. Foto: Erik van 't Hullenaar

Wilhelm Huck. Foto: Erik van 't Hullenaar

€97 million for a fully automated chemistry lab, €80 million towards artificial intelligence in education. Radboud University is winning one mega grant after another. How do you spend such immense sums of money effectively? ‘You have to be careful not to become a small NWO.’

€101 million. That was the amount Wilhelm Huck and his colleagues initially arrived at when calculating their grant application to the National Growth Fund. Now, if we get below that psychological threshold of 100 million, we will surely have a slightly better chance, thought the Professor of Physical-Organic Chemistry. So they adjusted their plans. ‘We managed to get it down to 99 million, but that didn’t feel right either. It made us look like the Lidl discount among Growth Fund applications.’

‘It made us look like the Lidl discount among Growth Fund applications’

In the end, they applied for €97 million. In April last year, the good news came from The Hague: their project proposal for a Robot Lab had been approved. The staggering amount was a new high on an already impressive list. Brand-new Professor of Educational Sciences Inge Molenaar was also awarded a Growth Fund grant: €80 million for research on artificial intelligence in education. And last year, Professor of Neuroscience Francesco Battaglia was awarded €21.9 million by the Dutch Research Council (NWO) for research into the workings of the brain.

These are sums that an average researcher will not even raise in the course of a decades-long career. Is it really necessary to spend so much money on a single project? And how do you spend all those millions? To start with the first question: such grants are essential to achieve real innovation. At least that is Huck’s firm belief, as he tells us in his study on the third floor of the Huygens building.

Beer or medicine

Consider his own Robot Lab project, which aims to build a fully automated chemistry lab, where robots take over all human operations. Pipetting, mixing substances, placing samples into analytical devices – these are still relatively labour-intensive operations that take up a good part of the working day of chemistry researchers and lab technicians. In this respect, not much has changed since the time of the alchemists in the sixteenth century. The idea is that at the Robot Lab, autonomous robots will take over this manual work. Regardless of whether you want to make beer, medicine, or paint, all processes will be streamlined by artificial intelligence.

You don’t build this kind of fully automated yet multifunctional lab on a small grant, Huck argues. ‘It costs tens of millions in investment. It’s something everyone in the chemical and food industries wants, but developing it is too risky for companies, due to the complexity. So without public investment, it will never get off the ground.’ The National Growth Fund should counter this kind of ‘market failure’. The money comes from the budget of the Ministry of Economic Affairs.

New Vox

This story is part of the new Vox magazine, which is all about money. After some good years, the university is back to budget cuts. And not just the university, but its students as well, with the cost of living on a steep incline. Fortunately, the return of the basic study grant can help to stop the bleeding.

Still, €97 million? You could also use this money to build an entire new university building, like the Maria Montessori building (price tag: €75 million). Or almost a city bridge like the Oversteek (€148 million). Aren’t these more sensible uses of public funds? According to Huck, you should also think of the Robot Lab as a major infrastructure project. ‘We also have to deliver a physical product, namely a lab that companies and other institutions can use.’

‘And nearly €100 million may sound like a lot,’ says grant advisor Pieter Jan Boon, who was closely involved in Huck’s application, ‘but this money is spread over eight years and five project partners.’ Huck may be a figurehead, but there are dozens of researchers in the consortium. Apart from Radboud University staff, there are researchers from Eindhoven University of Technology, the University of Groningen, Fontys University of Applied Sciences, and physics institute AMOLF. Per partner, this amounts to an annual budget of €0.8 to €3 million, Boon calculates. ‘This changes the perspective considerably, bringing it much more in line with a large individual research grant.’ For example, a five-year ERC Advanced Grant can go up to €3 million. By comparison, Radboud University has approximately €700 million in annual revenue.

No transfer

With mega projects, a lot of things work differently. For example, there is no maximum budget to apply for. Huck explains that this requires a totally different approach from, say, a Vidi grant proposal, which allows researchers with several years of experience to set up their own research group. Vidi grants always amount to maximum €800,000, enough for the salary of the applicant, one or two PhD candidates, and some equipment.

The Growth Fund works the other way round: the project goal, in Huck’s case an automated lab, is central, and from there you determine what you think you will need to get there. Huck: ‘You can only make an overall estimate, not a detailed calculation.’ Approximately how many people will you need and how much do they cost? And how much equipment? Eventually, this is how you arrive at a list with numbers of PhD candidates, postdocs, and material.

‘An advanced pipetting robot can easily cost €600,000’

In practice, the vast majority of the Robot Lab project’s budget (about 80%) is spent on people and material. In this context, the Chemistry Professor estimates that the ratio of staff costs to materials is about 3:1, compared to 5:1 for an NWO grant. ‘Our goal is to create an autonomous lab. So we need to invest a lot in analytical tools. An advanced pipetting robot can easily cost €600,000.’

Another important difference is that the Growth Fund money is not simply transferred all at once to the University’s bank account. ‘That is a big misunderstanding,’ sighs Boon. Payout is incremental. In October or November of this year, the government will transfer the first four-year tranche of €51 million. In practice, that money is transferred in annual portions. Boon: ‘The second tranche has to be applied for separately in four years’ time. Every year we have to account for our spending, and halfway through the project there’s a substantive evaluation.’

There’s also no guarantee that every partner will simply get the money that was reserved. The plan, Huck explains, is that all consortium members will soon be able to apply for funds from the project board, which will honour the project ideas that best match each other in terms of content. The project board is part of a specially created foundation that is separate from the University; its members are Huck and the principal investigators of the other project partners. The foundation is allocated the money and channels it back to the universities concerned.

Trial and error

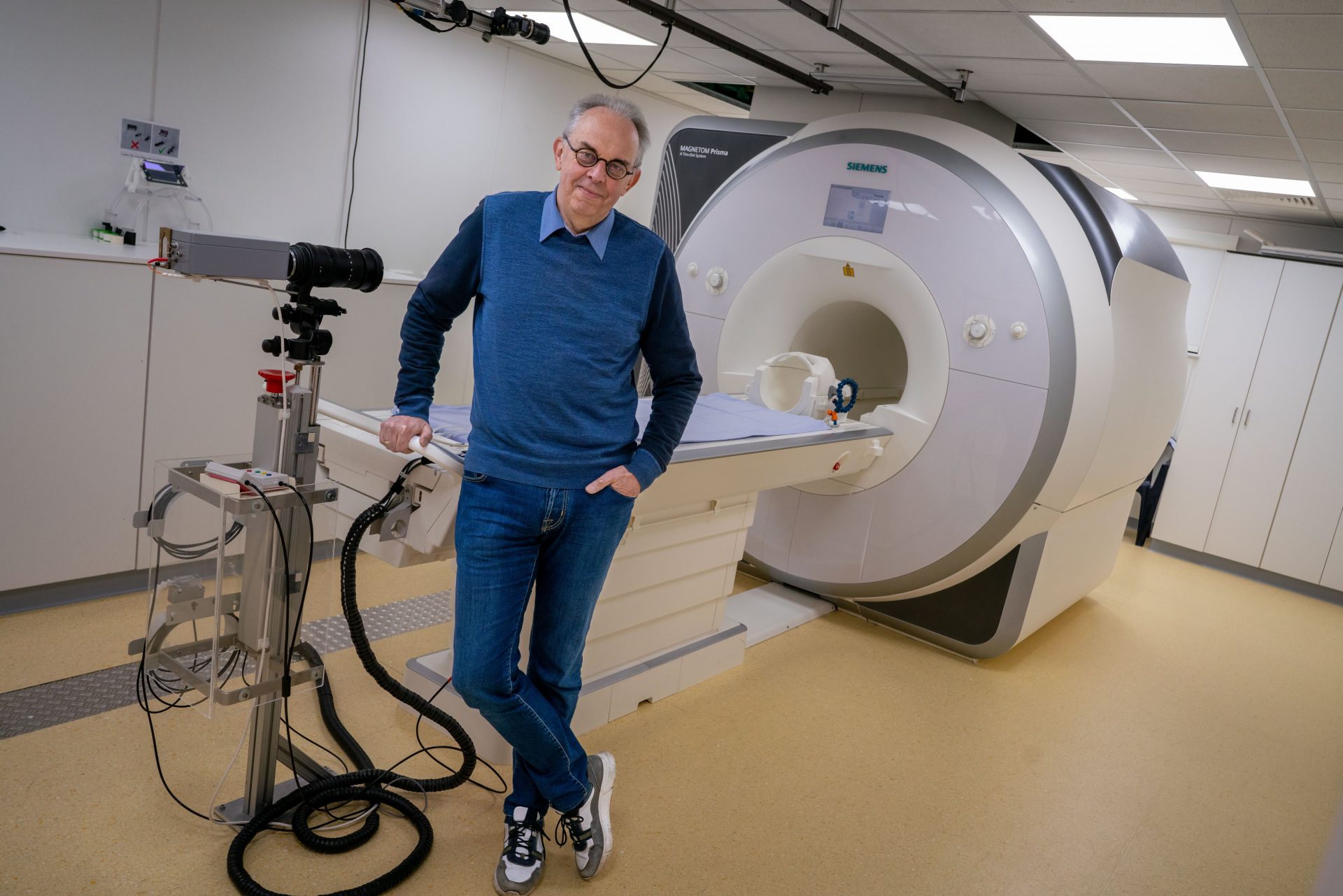

While Huck is still in the starting blocks of his new mega project, neuroscientist Peter Hagoort has almost crossed the finish line. Ten years ago, a research consortium that he led was awarded a €26.7 million NWO grant for the Language in Interaction project, a study of the biological, linguistic, and psychological aspects of human language. Three quarters of the budget went to Nijmegen: to the Donders Institute, the Max Planck Institute (MPI), and the Centre for Language Studies of the Faculty of Arts. The project is due to end in June 2024.

‘This is how you encourage mutual cross-pollination’

Managing such a large research programme involves trial and error, Hagoort reflects in his MPI office. ‘You have to be especially careful not to become a small NWO.’ What he means by that is that researchers might start to see the consortium as a glorified ATM machine for raising money for their existing research projects. ‘What we wanted was to tackle big questions that can only be answered by working together.’

That is why, just as with Wilhelm Huck’s Robot Lab, the Language in Interaction funds were not distributed all at once to all the researchers involved. ‘That isn’t possible with such a large and long-term project,’ says Hagoort. ‘This kind of consortium is like a living organism that goes through all kinds of new developments in its lifetime. For example, you want to do follow-up experiments based on new research.’ Moreover, the composition of the consortium is constantly changing: people are constantly dropping out or joining in. ‘In fact, sadly, two of the professors involved, Anne Cutler and Pieter Muysken, have passed away.’

Cross-pollination

To spend the funds most effectively, Hagoort and consorts opted for a construction that was similar to Huck’s. Consortium members could submit applications to a scientific board composed of researchers who were not involved in the project. The best rated plans were honoured. Plans from researchers who had never worked together before were given priority in this regard. Hagoort: ‘This is how you encourage mutual cross-pollination.’

At a later stage, the project managers drew up Five Big Questions that were to become central to the project. One of these questions was: Why does language capacity differ from person to person? Why are some people more eloquent than others or are able to learn a foreign language more easily? The answer lay in differences in how brain regions are connected. This was revealed by running scans with hundreds of subjects – from less educated to highly educated, and from young to old. Hagoort: ‘This kind of groundbreaking research is logistically impossible to do in the context of a small project.’

In hindsight, he would have liked to do some things differently, Hagoort now says. Like formulate those Five Big Questions earlier. ‘Everyone wanted to get started as soon as the money was allocated. This makes sense, but it actually would have been better to write a position paper [a theoretical paper with hypotheses, Eds.] as a consortium at the start. That way you work together right from the start.’

Peaks and valleys

Hagoort and Huck are aware of the fact that they are in a luxury position. And to be honest, Language in Interaction could in retrospect have done with a few million less, Hagoort thinks. Still, he says, there is a lot to be said for large grants like the Growth Fund and NWO’s Gravity Programme. And not only because of the economies of scale. ‘You need peaks and valleys in the scientific landscape, not flat lowlands. If you have top-notch research in house, you should continue to encourage it. Otherwise, foreign talent will stop coming here.’

Incidentally, this doesn’t mean that top research should come at the expense of smaller disciplines, he stresses. ‘Today’s society needs a broad knowledge immune system. That’s why I think that Starter Grants [€156 million to support starting assistant professors, Eds.] are also very welcome.’

A major focus for Huck and Hagoort is the period after their mega projects. Hagoort: ‘You want to prevent everything from collapsing like a plum pudding.’ That is why he is currently applying for a large follow-up grant within the new NWO Summit programme. Tenure track researchers have also been appointed within the consortium and these positions are now funded by the relevant faculties in Nijmegen and Amsterdam.

Within Huck’s Robot Lab, people are also already working to guarantee continuity, says grant advisor Boon. For example, the intention is for companies to start investing in the lab, hopefully making more funding available in a few years’ time. ‘That’s why it’s called the Growth Fund.’ Within the project, €11 million has been set aside for this purpose. The lab will ultimately have to keep running once the subsidy pot is empty, and the foundation will become a company: Robot Lab Ltd. Provided the researchers can deliver on their promises, of course. Huck is hopeful, but gives no guarantees. ‘I personally don’t know yet whether it will work out, but that’s inherent in this type of research. It really is high risk, high gain.

Overhead costs

Researchers sometimes complain about the money they spend on overhead costs. This is the amount the University skims from a grant to pay for general expenses. Think accommodation, cleaning, and secretarial support. ‘From my last ERC Advanced project, I had to pay half a million euros to the Faculty, which is 20%,’ grumbles Professor of Physical-Organic Chemistry Wilhelm Huck. ‘Of course, the University also has to pay its electricity bill, but those overhead costs also go to a thousand and one things, and I do wonder how essential they are. Think valorisation, coaching, and communication departments.’

Huck fears that it may even lead to competitive disadvantage. ‘On an ERC application, I have to specify that the grant needs to fund 30% of my salary. When of course, my salary will get paid anyway. At other universities, you only have to specify that you will devote 30% of your time to the project. So then you have some money left for, say, an additional PhD candidate.’

The differences between universities, says grant advisor Pieter Jan Boon, are not so much related to ERC requirements (which are the same everywhere), but to how grant winners can compensate for that 30% extra time and income. Some may reduce their teaching hours, while others get additional PhD candidates. ‘That is something grant winners agree on with their faculty. This is custom work and it varies per university or even faculty.’