Astronomer Klein Wolt in the race for science prize

Making a TV programme completely about your own research. That’s the dream of many scientists, and for astronomer Marc Klein Wolt of the Radboud Radiolab in Nijmegen, it may soon be reality.

Together with nine others, the radio astronomer has been nominated for the Klokhuis Science Prize. The candidate with the most votes will be invited to fill an entire broadcast of this Dutch children’s programme with their research. Beginning this Wednesday, children can vote via klokhuis.nl. The winner will be announced during the science festival InScience on 6 November.

The Nobel Prizes are being announced this week. Doesn’t a prize from Klokhuis pale in comparison?

‘Haha, well, I think this is actually the most important science prize in the Netherlands! What’s more important than making children enthusiastic about science and technology? I really enjoy that. You have to be able to grab the attention of the next generation. Moreover, if you can explain your research to children, then you can explain it to anyone. Children ask clever questions.’

‘I want to show them that they can achieve a lot if they follow their curiosity and experiment with things. That’s how it worked with that satellite that’s now circling the back side of the moon. Everyone said we were crazy when we wanted to accomplish that in two years – together with China, no less, who are not the easiest of partners. But now it exists.’

How did you come into contact with Het Klokhuis?

‘It had never occurred to me that we might be eligible for this, but the faculty’s media relations office suggested it. I had to write a short article explaining my research to children. And now we’re among the final candidates.’

Why is that?

‘I think that my research appeals to the imagination of many children. Space travel, the moon, they love that. With our satellite at the back side of the moon (see insert, ed.) we’re now listening to the sounds of the big bang and other objects in space.’

But… there isn’t any sound in space because it’s almost a vacuum?

‘That’s right. We capture radio emissions and transform them into sound to make them tangible. Take a radio pulsar, for example. That’s a sort of cosmic lighthouse that revolves on its axis hundreds of times a second while transmitting radio pulses. It’s really cool to make something like that audible. That immediately provides insight into what we’re talking about – namely, that one pulsar revolves faster than the other.’

Why should we listen to space if we can just look at it with telescopes like the Hubble?

‘Looking is useful only if there’s something to see. In the beginning of the universe there weren’t any stars emitting light. They came into existence only a few hundred million years after the big bang. If you want to discover what happened before that, what the universe looked like then, you’ll have to listen. Because radio emissions did exist at that time.’

‘They almost hugged me. A reaction like that is so very satisfying.’

Do you work with children more often?

‘Yes, even outside of the Netherlands. I’ve just visited all sorts of schools in Namibia at the border with Angola. I’m helping to build a radio telescope there, a new component of the Event Horizon Telescope that made the first photos of a black hole. Via the schools I hope to increase people’s support for the project and introduce children to astronomy. By taking them into a mobile planetarium (a large, inflatable cupola onto which planets, stars and the universe can be projected, ed.), I can stimulate their interest in both science and technology.’

And does that work?

‘Let me give you an example. At one of the schools in Namibia, there was a group of girls who initially thought: What’s this got to do with us? We want to be something else when we grow up, like doctors or policewomen. Then I asked: Don’t you want to see the world from another perspective? They finally agreed. They were amazed when they left the planetarium. They’d never seen anything so wonderful, they stammered. They almost hugged me. A reaction like that is so very satisfying.’

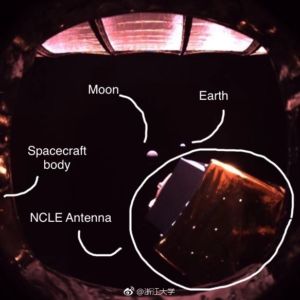

Partly thanks to Marc Klein Wolt, a radio antenna has been in place on the back side of the moon since February. The Netherlands-China Low-Frequency Explorer (NCLE) – of the Radboud Radio Lab, the research institute ASTRON and the company ISIS – was on board the Chinese Chang’e 4-rocket. At a distance of about 65,000 kilometres behind the moon, the equipment measures low-frequency radio signals, some of which are from the earliest years of the universe.

The extraterrestrial measuring location is necessary because the Earth’s atmosphere blocks low-frequency radiation and because the location behind the moon prevents interference from signals from the Earth itself, like our own FM and AM radio transmitters. The moon has no atmosphere and functions as a sort of shield against the disturbing emissions from Earth.