Bart Jacobs: a principled critic who does not yield easily

-

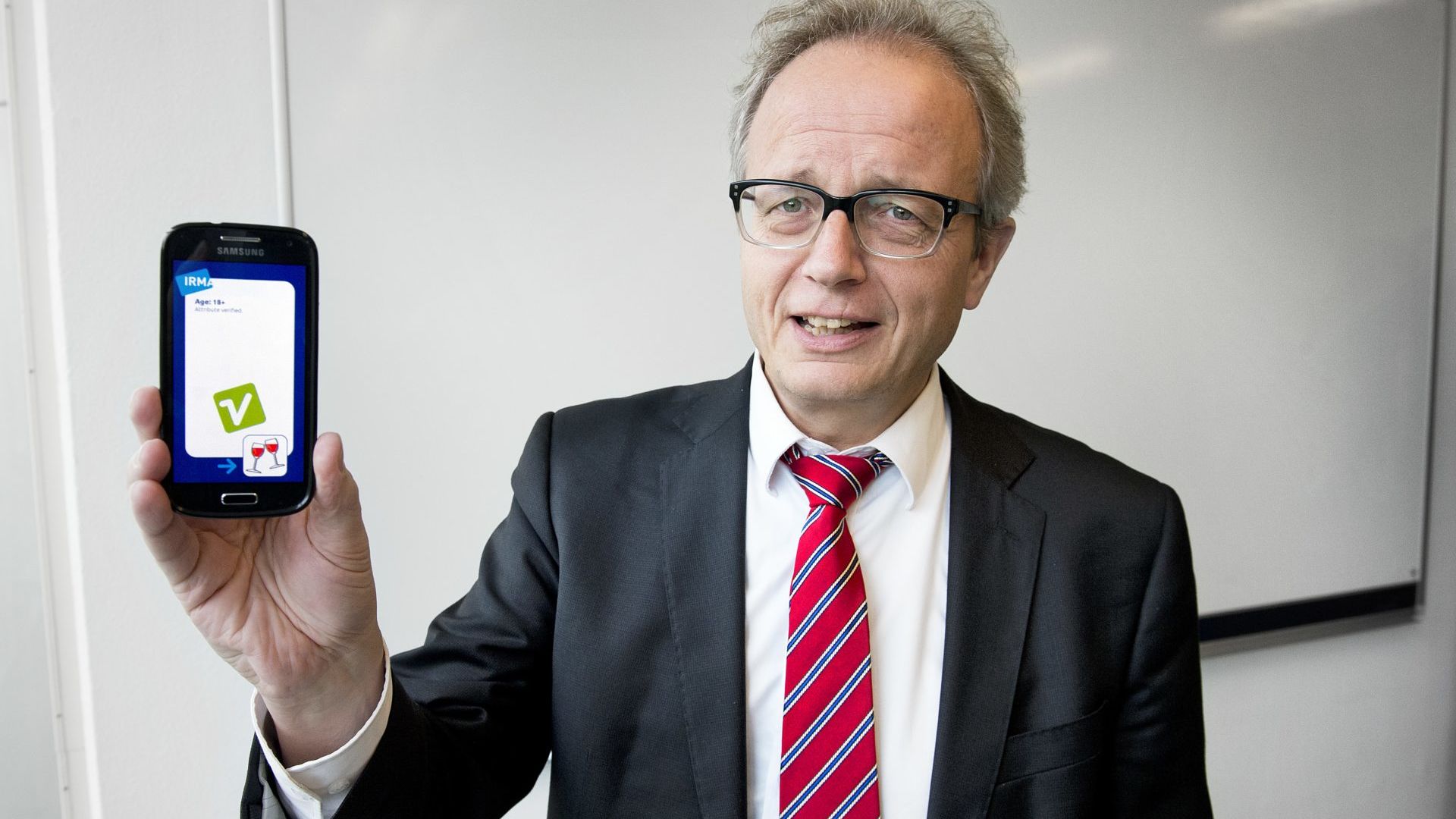

Bart Jacobs demonstrates the IRMA app he developed. Photography: Bert Beelen

Bart Jacobs demonstrates the IRMA app he developed. Photography: Bert Beelen

Last month, Professor Bart Jacobs won the prestigious Stevin Prize. What makes the cyber security expert so successful? A profile of a ‘hopeful cynic’ who’s not afraid of confronting big companies.

When his staff informed him one Friday morning in 2008 that they had succeeded in hacking the Radboud University access pass, Professor Bart Jacobs knew that it was serious. Across the world, billions of access passes were circulating with precisely the same Mifare chip. It was built into the OV-chipkaart for example. If the hack became public, it would make world news. ‘Bart immediately called Roelof de Wijkerslooth de Weerdesteyn, the then President of the Executive Board,’ remembers Wouter Teepe, a postdoc at the time and one of the ‘young bloods’ who had dissected the chip down to its bones. ‘Within a few hours, we got a call from the AIVD intelligence services, asking whether they could drop by for a cup of coffee.’

Chip developer NXP wanted to keep the chip’s vulnerability secret and tried to convince the government to go along with their strategy. But Jacobs soon made it clear to the AIVD that imposing a gagging order would not work – quite apart from his principled objections to such a step. Teepe: ‘These are young researchers and students, Bart said. They spend time at the café with their friends every week. It’s impossible to stop this news from coming out, so it’s better to make it public in a controlled way.’

The AIVD understood this, but NXP didn’t, even though Jacobs had informed the company of the problems in time – as is customary in the field. NXP held both the University and Jacobs personally liable for potential damage, since billions of chips worldwide would have to be replaced once the news about the chip’s vulnerability came out. Jacobs didn’t yield, and together with Radboud University, he won the ensuing lawsuit. This principled stance is one of the reasons why the Professor of Security, Privacy and Identity was awarded the Stevin Prize last month (see box on Stevin Prize). ‘He’s a truly independent thinker,’ said the jury, ‘and he’s not afraid to speak up’.

Stevin Prize

De Stevin Prize is intended for researchers whose research is revealed to have crucial importance for society. Together with the Spinoza Prize, which is awarded to researchers in the world top, the prize is seen as the highest scientific award of the Netherlands. The prize money – which amounts to € 2.5 million – can be used by winners at their own discretion to further their work. The Stevin Prize was awarded for the first time in 2018, to Marion Koopmans (ErasmusMC) and Beatrice de Graaf (Utrecht University). Bart Jacobs previously won the Brouwer Prize and the Huibregtsen Prize for the societal impact of his research.

Teepe, other colleagues and ex-colleagues of Jacobs that Vox spoke to all agree that Jacobs is working tirelessly to disclose the many dangers lurking around digital systems and the consequences this has for the privacy of citizens who inadvertently put their personal data in the hands of companies and government organisations, as well as the risk of this data being misused by hackers or for commercial purposes.

‘He’s always found privacy very important,’ says Marieke Huisman, UT Professor of Software Reliability and Jacobs’ first PhD student back in the 1990s. ‘I can still remember him not wanting his date of birth to appear on an NS chip card. It was clearly not necessary, he said.’ When Jacobs’ group hacked the Mifare chip, he made a conscious choice to seek out the media, she explains. ‘He finds it important that people become aware of what can go wrong.’

‘He finds it important that people become aware of what can go wrong’

By consistently communicating this message, he has built clear communication lines with the media. Huisman: ‘One of the things I’ve learnt from him is that you have to be able to explain your research in less than a minute.’ It is therefore not so strange that Jacobs should be awarded the Stevin Prize precisely for his impact on society.

Genuine curiosity

But there are other reasons for this award than media attention alone, emphasise those who know him. What really makes Jacobs unique, they say, is his incredible wide range of interests, both personal and professional. Trained as a mathematician and philosopher (see box), he’s genuinely curious about topics outside his field of expertise, says Tamar Sharon, who was appointed Professor of Philosophy, Digitalization and Society in Nijmegen last month. When she was still an assistant professor in Maastricht, someone encouraged her to contact the Nijmegen Professor. ‘He immediately invited me to give a presentation on the ethical and social consequences of technological developments to his research group of mostly computer scientists. And that while he wasn’t yet familiar with my work.’

The invitation was not just a polite gesture. A few months later, Jacobs asked Sharon to help him set up iHub in Nijmegen, an interdisciplinary research institute in digitalization and society. ‘Sure,’ I said, ‘I’d love to!’

Biography of Bart Jacobs

Bart Jacobs (1963) studied mathematics and philosophy in Nijmegen. During and after his PhD he specialised in logic and probability theory. He wrote a number of books in this field that are still used as standard works today, and he won an important ERC Advanced Grant. With time, his interest shifted to cyber security and privacy. Based on his expertise, he was invited to join various governmental committees, including the Cyber Security Council and the CTIVD Knowledge Network, a committee responsible for ascertaining whether the Dutch secret services act lawfully. Jacobs is a member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Sciences (KNAW) and Academia Europaea.

Jacobs soon understood that cyber security problems could not be solved by legal experts and computer scientists in isolation. Rather, they involved economic, ethical and behavioural aspects. Chips like the one used by the OV-chipkaart or Volkswagen – another company that was denounced by Jacobs – could be hacked because companies opted for cheaper but unsafe chip variants. ‘And why do people fall for phishing mails?’ says Frederik Zuiderveen Borgesius, Professor of ICT & Law at iHub. ‘These kinds of questions are also relevant. It makes little sense to place the problem with the users. It’s better to look for solutions together with behavioural scientists.’ iHub bundles all these kinds of expertise within Radboud University.

Alcohol

In creating the IRMA app, one of Jacobs’ showpieces, all of these aspects were taken into account. The app allows people to identify themselves digitally – for example when buying alcohol in a shop – while retaining full control of the data they show: birth year, but not gender, for example. This makes the app much more privacy-friendly than a regular passport. ‘Passports contain a lot of personal information that doesn’t need to be shared at all,’ says Zuiderveen Borgesius.

Jacob’s plans to build a new social media platform together with Spinoza Prize winner Van Dijck – the two prizes were awarded at the same time – is perfectly in line with these priorities. Van Dijck is Professor of Media and Digital Society at Utrecht University. Their joined new social network will be a civilised and privacy-friendly system, with various sanction mechanisms in place to prevent discussions from digressing or degenerating. So far, the network only exists on paper, but Jacobs hopes that a preliminary test version will be available within one a year, he told NRC.

This kind of spontaneous collaboration is typical of Jacobs, says Ronald Leenes, Professor of Regulation by Technology in Tilburg. ‘He sees an opportunity and acts on it. Together, they have € 5 million to make this happen. And they’ll need it, because just having a great idea is not enough. You need support to generate publicity for your product, which costs a lot of money.’ This is something Jacobs definitely learnt from his experience with IRMA, thinks Leenes. Despite the app’s usefulness, the number of places where it can be used is limited. Although the EU has announced its intention to apply the IRMA principles.

Ten spades deep

Jacobs is clearly not the only multidisciplinary researcher around, but what distinguishes him from others, according to many people, is the way he combines breadth and depth. ‘He’s one of the few who can do so,’ says Bibi van den Berg, Professor of Cybersecurity Governance in Leiden. ‘Where other multidisciplinary researchers only go two spades deep, his knowledge of pure mathematics reaches ten spades deep.’

This interest in other disciplines goes back a long way, says Zuiderveen Borgesius. ‘Fifteen years ago, he already added a legal course to the cyber security curriculum, as a compulsory element.’ Nowadays this is relatively normal, but at the time, it was a pioneering step. I also regularly met him at legal conferences in those days.’

This is precisely what has given him an edge on many others in his field, adds Van den Berg. ‘Jacobs saw early on that there were problems around cyber security and privacy; he really has a nose for it. As a result, he was always ahead of the game.’

‘When a guest came over, he would go past all offices inviting everyone to join him for a meal out’

It’s one thing to bring various areas of expertise together but keeping them together requires different skills. However, this is also one of Jacobs’ qualities. With his sense of humour, he creates a social and inspiring atmosphere at iHub, says Zuiderveen Borgesius. ‘He’s very approachable and genuinely interested, also in junior researchers,’ add Sharon. Former PhD candidate Huisman calls Jacobs’ first research group, of which she was a member, a ‘friends’ club’. ‘When a guest came over for a lecture, he would go past all offices inviting everyone to join him for a meal out.’

Respectful

When it comes to content, Jacobs is less into socialising. ‘Like many other researchers he can be impatient at times when people digress too much or are not concrete enough,’ laughs Van den Berg. ‘“Shall we get back to the content,” he says. And then, in a few sentences, he brings the conversation back to what it’s actually about. This clarity is incredibly helpful.’

Some people are less charmed by his style, including a colleague who wishes to remain anonymous. ‘He’s very sure of himself and likes to be at the centre of attention as the best one in his field.’ This colleague is under the impression that Jacobs is actually not open enough to alternative ideas.

Either way, Jacobs is not a pleaser who agrees with everyone. Leenes: ‘It’s very refreshing to see Bart take a stance, for example when organisations drop stitches when it comes to system security.’ He sticks his neck out, he says, even with big companies, like Volkswagen or NXP, that have large legal departments.

Chipkaart hacker Teepe also values this attitude. ‘Sometimes you have to be a principled pain-in-the-ass, there’s nothing wrong with that. In doing so, he’s doing society – and the University – a great service, even if they don’t always realise it at the time.’ Or, as iHub co-director Sharon puts it: ‘In that respect, he’s a hopeful cynic.’