Dutch academics drink most often

-

Foto: Susanna Fernandez/Creative Commons

Foto: Susanna Fernandez/Creative Commons

Of all demographic groups in the Netherlands, academics drink alcohol most often. Their children copy their drinking behaviour, even if they themselves are lower on the social ladder. Nijmegen sociologists found this in a study that they conducted together with The Netherlands Institute for Social Research.

The study uses data from the European Social Survey (ESS), in which Europeans report about, among other things, their lifestyle and health. To the sociologists’ surprise, the Netherlands ranks highest when it comes to alcohol use. Besides that, the difference between people with a higher education level and people with a lower education level is quite big.

In most areas, people with a higher education level make healthier choices than others: they smoke less, exercise more, eat more vegetables and more fruit. This is the same as in most European countries, the research shows, but the difference in the Netherlands is surprising. Only Finland, Portugal, Estonia and Latvia know a bigger gap between people with higher education and people with lower education, when it comes to health choices.

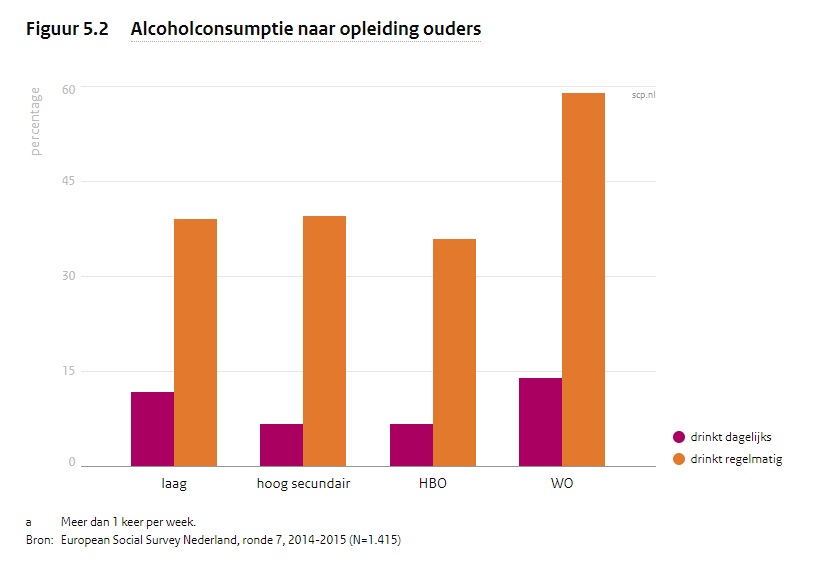

But academics allow themselves to feast on one thing: alcohol. Especially the academic who is over fifty-five years old. ‘It is part of their routine, drinks on Friday after work, a glass of red wine at dinner. It is a way to distinguish yourself’, explains associate professor social inequality Stéfanie André, who contributed to the study. When it comes to drinking, these academics not only differ from the lower educated, but also from people with a university of applied science degree. Out of all academics, 47 percent drinks regulary, next to 42 percent of applied scientists.

‘We can afford this’

Lifestyle is something you transfer on to your children. People with parents who are academics also drink regularly, more than once a week: almost 60 percent. For children of parents with lower education, this is 40 percent. If you have academic parents, you also drink more often: 14,2 percent drinks daily, against 6,8 percent of children who have parents with a university of applied science degree. ‘Even if children of academics never reach that level of education themselves, their drinking behaviour looks more like that of their parents than like that of their peers’, says André.

Portugal

Moreover, in most European countries people with a higher education level drink most often. An explanation for this could be that alcohol is not cheap. ‘Alcohol costs money and it could be a way to show “we can afford this” or “this is part of our way of life”‘, says André. In six countries, among which Portugal and Latvia, it is the other way around: people with lower education drink the most there.

André and her colleagues argue that, based on their results, health campaigns should distinguish between target groups even more often than they do now.