Farewell of Mikhail Katsnelson: ‘The first years were very difficult, but eventually Nijmegen became the ideal place for me’

-

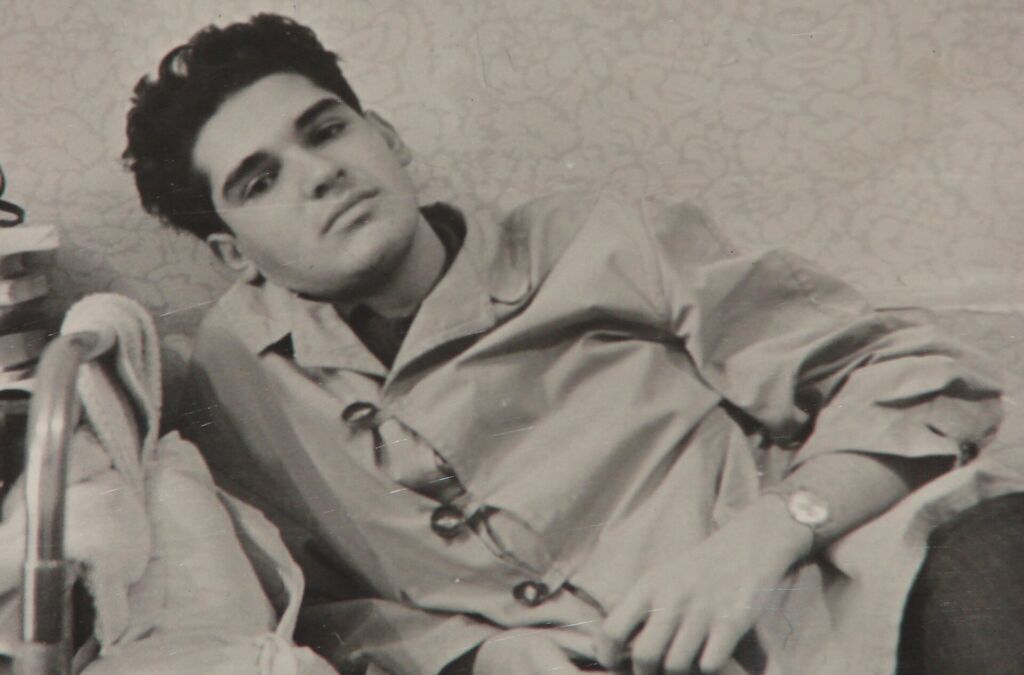

Foto: Bert Beelen

Foto: Bert Beelen

After a meteoric scientific start in the former Soviet Union, the career of physicist Mikhail Katsnelson came to a standstill in the late 1990s. Due to a feeling of hopelessness, he decided to move abroad and ended up in Nijmegen. There, Katsnelson secured substantial grants; he even contributed to research that earned a Nobel Prize.

He chose Nijmegen for entirely wrong reasons. That is Mikhail Katsnelson’s (1957) conclusion after 20 years as a professor at Radboud University. In 2004, the now world-famous physicist expected to arrive in a slow, somewhat sleepy place. It was just what he needed, after years of mounting tension and stress in his native Russia (more on that later).

‘A few scientific publications a year to keep the people around me satisfied, a bit of teaching, learning the language. Most of all, I was looking for a quiet place where I could relax and unwind.’ He did not expect much more from his academic career.

Little did he know how things would unfold.

‘Coming to Nijmegen actually turned out to be incredibly good for my scientific career,’ Katsnelson says with a smile in his soberly furnished office in the Huygens Building. ‘The general mood in Nijmegen in those days was: we may not be as well known and famous as the universities of Groningen, Utrecht and Leiden, but we should be on the same level. Young ambitious people were pushed to do their best. Before I knew it, I had become hugely active.’

Nobel Prize for graphene research

From the start, Katsnelson became involved in research on graphene, a two-dimensional, super-strong material, for which his fellow researchers Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2010, and in which Katsnelson played an important role.

The three researchers of Russian origin first got to know each other better in Nijmegen, at a party following Novoselov’s PhD defence. As Radboud University Professor of Theoretical Physics specialised in magnetism, Katsnelson had already published on the physical properties of this two-dimensional carbon molecule even before graphene was discovered.

At the party in question, Andre Geim asked Katsnelson a few graphene-related questions, which he managed to answer very quickly and accurately. That marked the start of a fruitful collaboration. Without Katsnelson’s work, Geim later stated in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, the research would never have gotten so far in such a short time.

Magnitogorsk

Mikhail Katsnelson grew up in the Russian city of Magnitogorsk. An industrial town built from scratch in 1929 around the country’s largest iron and steel plant. In 1932, Nijmegen filmmaker Joris Ivens made a somewhat controversial film about it, entitled The Song of Heroes. In the film, Ivens did film the international volunteers who helped build the new city, but not the tens of thousands of forced labourers.

‘Until I was four, we lived on the highly polluted left bank of the Ural River’

Katsnelson’s parents grew up in what is now Ukraine. They met after the Second World War in a state-run hospital in Magnitogorsk. ‘My mother worked there as a surgeon and my father as a dermatologist. Before the war, my father had also worked as a surgeon, but due to some injuries to his hands he suffered while in military service, he could no longer do that work.’

In 1957, the couple had a son, Mikhail. For a long time, Katsnelson believed he was his parents’ only child. He later found out that he briefly had an older sister. ‘She died shortly after birth. A sad event, which was little talked about.’

How do you look back on your childhood?

‘I would say it was pretty good by Soviet standards. We were not rich, but because my parents were doctors I probably had it a little better than most kids my age.’

‘Until I was four, we lived on the highly polluted left bank of the Ural River. It was a terrible place where you could hardly breathe because of the red and black factory smoke. So when we were offered a new two-bedroom flat on the much cleaner right bank, we were very happy.’

‘Still, my parents were always very busy. They worked long hours, also during nights and weekends, as is common in places where there are few doctors.’

How did your parents’ absence colour your life at the time?

‘My parents paid little attention to me. I was alone most of the time. I spent a lot of time with other kids on the streets. That kind of industrial city clearly has a specific kind of culture; street life was pretty brutal. I was not really part of a group of young gangsters, but I did hang out with them.’

‘On the other hand, I started to read very early. Thanks to my well-educated parents, we had lots of books at home. By age four, I had pretty much taught myself to read fluently. Looking back, I think communication with children on the street and the books at our home were the two main influences in my childhood.’

What did you do with your parents when they did have time?

‘We went on holiday together. Although it was rare for the three of us to go anywhere; I would usually go with my mother, sometimes also with my father. I was seriously ill as a child: I had a kidney condition that I thankfully grew out of. But that meant that it was good for me to go to warm places. When we could afford it, we went to Crimea on the Black Sea, but more often we stayed nearby, for example in the mountains of Bashkiria.’

How do you look back on your school days?

‘Initially, I was terribly bored at school, until some competent teachers realised that I was ahead of the game. I was challenged more and allowed to skip a year twice, which meant I finished school at 14.’

‘In retrospect, I think it was fortunate that I finished school so early. During that time, my father became seriously ill; he developed cancer and died when I was almost done with school. If I had had to go to school for a few more years after he died, I think it would have been a lot harder for me.’

‘At school, I was a bit of an outsider’

After his father’s death, Katsnelson left for university in Yekaterinburg (then Sverdlovsk), about a six-hour drive from Magnitogorsk. At 15, he was a lot younger than the other students, but he found more connection there than at school.

‘This marked the start of a great period in my life, when I became much more social. In my first year, I shared a room with four senior students, who happily ignored me, ha ha. In the second year, I moved in with friends.’

You found more connection with peers in your student days than in your hometown?

‘At school, I was a bit of an outsider, partly because of my young age. I did not look very nice as a child. I was quite weak, not very athletic, a bit too fat. But by the time I went to university, I was much stronger physically and I had already grown considerably.’

‘As a student, I was never alone, there were always other boys in the same room. If there was talk and drinking late into the night, you had to join in. It taught me how to communicate with others and I look back fondly on this period in my life.’

‘I would sometimes miss lectures because of all the nighttime activities. When that happened, I was allowed to copy the notes of my well-organised friend Sascha (Alexander Lichtenstein, professor at Hamburg University, eds.). When I was a fourth-year student, my mother also moved to Sverlovsk and I moved back in with her.’

You started doing research early on alongside your studies.

‘Yes, that started already in my second year, thanks to my then lecturer Boris Ishmukhametov, one of the most important influences in my life. He saw in me a talented student and involved me in his projects. Ishmukhametov became a kind of second father to me: I would go to his house a lot, and we played chess together. He not only taught me a lot about science, but also about art, music and literature, which I knew nothing about because of my background.’

‘Thanks to the research work I was allowed to do for him, I was a reasonably well-known and successful scientist by the end of my studies. One of my professors then recommended me to Serghey Vonsovsky, an outstanding physicist and a very big boss. He was the head of the Ural Division of the Soviet Academy of Sciences.’

A dangerous time

The influential physicist Vonsovsky took the young Katsnelson under his wing and introduced him to other important scientists. He asked him to take over his lectures when he could not teach himself, enables Katsnelson to get his PhD at an early stage and had him co-author the textbook Quantum Solid-State Physics. At 28, Katsnelson was promoted to Doctor of Science, a position similar to a full professorship. This made him the youngest Doctor of Science in Physics in the former Soviet Union. But this was not to everyone’s liking.

‘I started noticing that a lot of people were really pissed off. Prior to this, everyone had loved me, I had been the nice, young, talented guy. But when I became a professor at a very young age and also received a prestigious state award for young researchers, the Lenin Komsomol Prize, that began to change. The atmosphere around me became more hostile.’

Not long after this, in the late 1980s, the Soviet Union began to fall apart. Many scientists decided to pursue their careers elsewhere, but you stayed.

‘In the late 1980s, it was possible, in fact quite easy, to emigrate. Most talented people did. But together with my good friend Sasha Trefilov, I felt we were living in historical times. It was a chaotic and also violent time, but there was also a lot of optimism and hope.’

‘We decided to roll up our sleeves and build a new future. We were very politically active and wanted to change the educational system, for example by moving state-affiliated scientific institutes to independent universities.’

‘This period was fatal to my scientific career, because I was doing practically no research all those years. In the mid-1990s, when I travelled abroad more often, I saw Russian scientists with very successful careers, who in Soviet times had supposedly been “less important” than I was.’

At the start of the millennium, you did decide to go abroad after all. Why this turnaround?

‘After the chaos of Yeltsin’s rule, during which we at least still had some hope for change, Putin came to power. Incidentally, I didn’t consider him as a bad guy at the time. His slogan was stability. That was when I realised: nobody is going to change anything, and the old system will survive.’

‘I felt I was living in an extremely unfriendly environment’

‘A lot had also happened for me personally in the preceding years. My mother died in 1997. While she had been alive, I did not want to emigrate because I did not want to leave her alone. And then, in 1998, Serghey Vonsovsky also died. His support had been extremely important to me because, as I said, I irritated a lot of people. Without him, the situation became slightly dangerous.’

Dangerous in what respect?

‘In many ways, it was a gangster time. There were countless ways in which people could show they were irritated with someone: by obstructing their career, but also by bashing their head in. I felt I was living in an extremely unfriendly environment.’

When did you realise it was time for a change?

‘Back then, I was already regularly visiting universities in Germany and the US, because I could earn many times more in a couple of months there than in a whole year at home. During one such exchange, I had breakfast with Professor Arthur Freeman, a highly renowned physicist at Northwestern University (Chicago) and a close friend of Vonsovsky. I told him about my situation and he asked why I did not leave Russia.’

‘I asked him why he thought I should. His answer was rather unexpected, he said: “To start with, because you will probably live 15 years longer.”’ He laughs.

‘And it was true, because at the time I was in a terrible state psychologically. I took poor care of myself, I drank too much, and I was overweight. I was really in a kind of depression, so I had to something.’

How did you then end up in Nijmegen?

‘Upon returning to my institute in Sverdlovsk, a heated discussion with the director made me realize I could no longer stay there. At the same time (in 2002 eds.), I was given the opportunity to go to Uppsala University in Sweden on a stipend. Still, I found it hard to leave for good. I went to Moscow to see my friend Sascha Treflov, who was already seriously ill by then, and I put my doubts to him.’

Katsnelson falls silent for a moment and clears his throat. ‘He said: “You should definitely not go back (to Sverdlovsk, eds.); I just want to ask you to come back for my funeral.’ He is clearly moved: ‘I promised him that I would. He died in 2003, far too young.’

‘Shortly after that conversation, I set myself an ultimatum: I would find an international position as a full professor within three years or else I would leave science. It was an impossible task, in which I miraculously succeeded.’

‘At Uppsala, I just could not get clarity on a permanent position, but in the meantime I had been asked to apply for a prestigious position at Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee. While still going through that procedure, I suddenly started getting offers from other universities as well. Including one from Radboud University, which I knew about because my friend Sascha Lichtenstein had worked here before.’

‘In the end, I decided to go for Nijmegen. For entirely wrong reasons, as I said, but it worked out incredibly well.’

Did you feel better straight away when you came to Nijmegen?

‘Not immediately. The first few years were very difficult. I naturally found myself in a society that was totally foreign to me and to which I had to get used. I wasn’t quite sure how to behave. At the time, I got a lot of support from Jan Kees Maan (founder and former director of the Highfield Magnet Laboratory eds.). He taught me about university politics and subtleties.’

‘But I have to say that the first few years I didn’t feel like I had really found a place where I wanted to stay.’

‘That changed in 2010, when the Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to graphene research. Not to me personally, of course, but people did see and appreciate my contribution to that research.’

What changed that made you feel more at home?

‘The success of graphene research made me a noteworthy person. I began to feel very supported within the University. I received the Radboud Science Award and was awarded the Spinoza Prize in 2013. I also secured large European grants and was allowed to lead a large research group. Over time, I was increasingly able to do more and more of what I liked. And so Nijmegen eventually did become the ideal place for me. Coming here was an extremely wise decision, although I didn’t know it at the time.’

Russia’s future

Katsnelson had married his wife Marina in 1982; she came to Nijmegen with her husband in 2004. She has also worked at Radboud University since 2011, as a staff member at the educational institute in Mathematics, Physics, and Astronomy. The couple had two children, a daughter and a son, who initially stayed in Russia, but have been living closer to their parents for several years.

How important is proximity to your children to you?

‘Extremely important. We also have five fantastic grandchildren who often come to visit.’

What kind of father were you to your children?

‘I am afraid I have not been such a good father to them. Because at a critical time, Marina had to take care of them on her own. I was always busy, always gone. To Moscow or abroad. I am afraid I did not pay enough attention to my family during this period.’

‘On the other hand, my absence was really necessary for our survival. In 1990s Russia, everyone was primarily concerned with survival. But looking back, I regret not being able to spend enough time with my family. That is why I am so happy that we now live close to each other and that I can see them regularly.’

‘My oldest granddaughter is seventeen now and we sometimes chat about science; she even asks me questions about Mathematics or Physics.’

Do you miss your native Russia?

He sighs deeply. ‘You know, the Soviet Union was so dramatically different from today’s Russia. Especially when it comes to everyday life and human relationships. Today’s Russia is a different country to the one I grew up in.’

‘Almost all the people who were once important to me are dead or have also left Russia’

‘Not that I was a big fan of the Soviet regime or the poverty-stricken life in a brutal industrial city. But still, I sometimes feel a kind of nostalgia, because it is where I grew up.’

‘But after more than 20 years in Nijmegen, I now feel at home here, and I also feel a strong connection with European academia. Plus, almost all the people who were once important to me are dead or have also left Russia.’

Can you still visit your country?

I think so. Why not? But I see no reason for it.’

Were you surprised when Russia launched a war with Ukraine?

‘Yes and no. There were indications, such as Russia’s tendency towards self-isolation, severing ties with Western countries, and increasingly aggressive propaganda. It happened gradually. But after the annexation of Crimea, in 2014, it was perfectly clear that Russia had chosen a course of hard confrontation with the West.’

‘Still, I don’t think anyone expected it to really lead to a full-scale war. Because what are the benefits? There aren’t any, not even for Putin.’

What kind of future do you see for Russia?

‘I don’t know. I don’t live there anymore and I have very little contact with people there. But I am quite pessimistic. I am afraid that this situation could continue for a very long time.’

In a interview with Trouw in 2014, you spoke about your faith in God. You converted when you were around 30 years old. Do you find a lot of support in your faith when it comes to issues like this?

‘In a way, it has actually become more difficult for me because I belong to the Russian Orthodox Church, which has chosen to fully support the Russian regime. They make extremely anti-Christian statements. I find that very painful.’

‘I do not think I am a bad person because my bishop is’

‘But on the other hand, I think we really need to separate religion and belief in such situations. I do not think I am a bad person because my bishop is. In the end, he will have to take responsibility for his sins and I for mine.’

On Thursday, you will give your farewell speech. What will you do once you retire?

‘Well of course that will depend on my health, but at the moment I feel I am in good shape, also intellectually. In the past two years, I took part in so many great projects. Therefore I think it would be stupid to quit because of formal reasons. I still have a European Synergy Grant, although Radboud University unfortunately does not allow me to apply for new grants. Perhaps I can do so elsewhere.’

So you plan to remain active in science and not do something completely different with your time?

‘I think it’s important for me to remain active. I have seen with other people who were as active as me what the physical and psychological consequences can be when you stop abruptly.’

‘Of course, I hope to travel more with my wife and children. And I agreed to become an editor at Annals of Physics, which is a very good journal.’

‘When I was seven years old, one of my father’s friends gave me a small mineral collection. That is a hobby I still enjoy. But most of all, I hope to find opportunities to continue to do research.’