Fewer rules and less hassle under new social benefits study

-

Illustrations: Simone Zwitserloot

Illustrations: Simone Zwitserloot

Radboud University and the Municipality of Nijmegen are joining forces as part of a new study for people on social benefits. The goal is to help people find employment more quickly and to make navigating the various regulations less stressful.

Those who visited the Stadswinkel in recent months to request a passport may have seen the posters: the Municipality of Nijmegen was looking for unemployed people on benefits who wanted to participate in an experiment conducted in collaboration with Radboud University. The objective was to make it easier to apply for benefits.

A study of social assistance benefits sounds a bit like a base salary. Confronted with this realisation, Radboud University sociologist Niels Spierings chose his words carefully: ‘The base salary has generated a lot of media attention, which is why it’s an easy link to make. Nevertheless, this really is something else’, he says. ‘As soon as the “b word” is mentioned, it invokes all kinds of political statements’, adds János Betkó, a municipal policy advisor and one of Spierings’ PhD candidates. ‘That’s not something we want.’

In other words: it’s not the same as a base salary. But that doesn’t make it any less interesting, according to Spierings and Betkó, who explain the study over a cup of coffee in the city hall canteen. As of 1 December, the welfare rules for three to four hundred social assistance benefit recipients will become more flexible for two years. These flexible rules are expected to help the recipients find work more quickly and have a positive effect on the mental and physical well-being of the participants. As an added benefit, this experiment may have important scientific implications as this is the first time more flexible social benefit rules have been investigated on this scale.

Distrust

The experiment is the result of a long-term political process initiated in 2015, when the municipality’s GroenLinks (Green Left) party submitted a proposal. The study was only greenlighted by the Dutch government last July. Spierings and fellow sociologist Maurice Gesthuizen were approached to steer the experiment in the right, scientifically sound direction. As an external PhD graduate, Betkó is responsible for the actual implementation of the study.

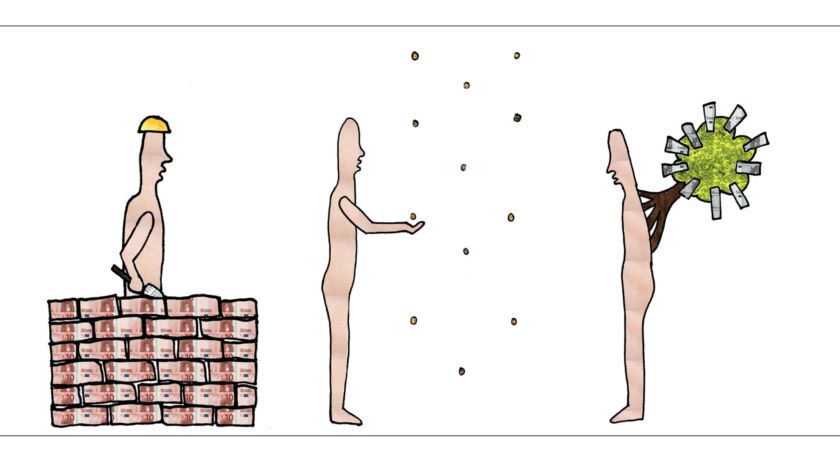

When GroenLinks and the SP presented concrete motions in late 2015, a large majority of the municipal council voted for them. The current system is based too heavily on distrust. Social benefit recipients cannot earn hardly any additional money without being ‘punished’ with reduced benefits. They also have to participate in work supervision, which involves, for example, working on their application skills and sending application letters. Unemployed people regularly get lost in the jungle of obligations, allowances and discounts, making their situation appear even more hopeless. ‘Take the story of a jobseeker who submitted his form a few days late and immediately received a €150 fine’, says Betkó. ‘That’s not the way to help these people.’

This strict regime will be a lot more relaxed for the study participants, who are allowed to keep half of the money they earn alongside their benefits, up to a maximum of €200 per month. This amount is not deducted from their benefits. The participants will be divided into three research groups, each with their own rules governing work supervision. One group will be entirely exempt from work supervision; one group will be required to participate in work supervision, but can determine what form this takes; and one group will receive standard work supervision.

Less room for thought

While the experiment may be great for the participants, the ultimate objective is that it generates measurable results. The municipality has earmarked approximately €750,000 for the study, which has also been awarded a European grant worth several hundreds of thousands of euros. This is a lot of money and a great investment, according to Alderman Jan Zoetelief. ‘It gives participants the opportunity to gain confidence and to re-engage as active members of society. If this helps to increase their sense of self-worth, we’ve made great strides.’

Self-confidence and self-worth aren’t the only things these benefit recipients can expect. Betkó and Spierings are basing their research on the ‘bandwidth theory’. In 2013, a group of Princeton economists published a paper with the simple title: ‘Poverty impedes cognitive function’. The ideas proposed in this paper were equally simple, but no less influential. Poverty takes up so much cognitive capacity that you have less room to think about ways to climb out of your financial hole. That’s why poor people often make decisions that don’t help them in the long term.

According to Betkó and Spierings, relaxing the benefits regulations will give poor people more room to think. ‘That’s why we expect a positive effect on the health and decision-making capabilities of our participants’, explains Betkó. ‘Room to earn extra money is an additional motivator in the search for a new job’, adds Spierings. ‘That will help reduce unemployment rates.’ It would surprise the researchers if the jobseekers didn’t improve during this study. ‘But we don’t know for sure, so it’s a good idea to test this in a reliable way’, says Spierings.

Unique study

It doesn’t surprise Spierings that the university was willing to collaborate with the municipality. ‘Experiments on the behaviour of benefit recipients have been done before under various circumstances, but most of these involved an artificial survey among a hundred or so psychology students.’

The Nijmegen benefits study is unique in that it mirrors reality: the benefit recipients are not being studied in a lab, but in their daily lives. As far as Betkó and Spierings are aware, this hasn’t been done before. ‘Everything will be based on sound scientific principles’, says Spierings. ‘So with a random distribution of test subjects across the groups and a control group to which the regular rules apply.’ Betkó adds: ‘It will take a lot of time and money, but all the benefit recipients have volunteered to take part. This study wouldn’t have been possible on this scale without the money provided by the municipality.’

What makes it even more interesting is that Nijmegen is not the only city to experiment with the benefits rules. Wageningen, Deventer, Tilburg and Groningen are starting their own studies. ‘Each municipality has its own focal points in the study’, says Spierings. ‘We’ll soon be able to combine part of the data from all of these cities and examine the effect of the subtle differences between the individual studies.’

The study will start in just over a month, on 1 December 2017. The new rules will apply for the participants until 1 October 2019. And then? ‘The follow-up will depend on the results’, says Betkó. ‘If the more relaxed rules prove to be very successful, the government may extend the study.’ Alderman Zoetelief wants to wait for the results. ‘We’ve just formed a new Cabinet, so we’ll have to wait and see whether they’re willing to change the rules. It’s a waiting game at this point.’