Follow-up Research into Suriname Life After Abolishment Slavery

-

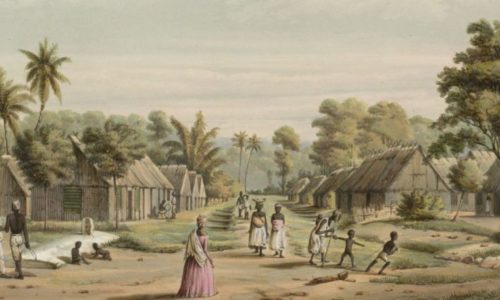

Slavenkamp in Suriname, jonkheer Jacob Eduard van Heemskerck van Beest, naar Gerard Voorduin, 1860 - 1862 (via Rijksmuseum)

Slavenkamp in Suriname, jonkheer Jacob Eduard van Heemskerck van Beest, naar Gerard Voorduin, 1860 - 1862 (via Rijksmuseum)

Slavery was abolished in Suriname in 1863. How did the people live their lives after being liberated? Did they find jobs? Who did they marry? Having previously published the slave registries, Historian Coen van Galen is now doing follow-up research on the lives of hundreds of thousands of Surinamese people after 1863.

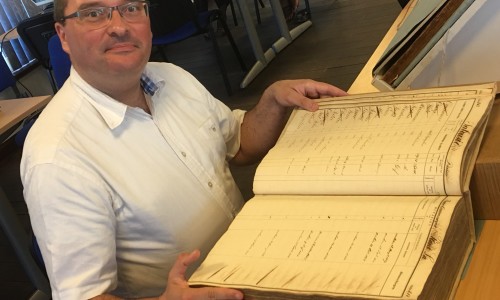

Suppose you were born in Suriname, and you wanted to map your ancestors’ lives. Thanks to previous research done by Coen van Galen, you would be able to find out if earlier generations of your family were enslaved on plantations, and which names they were given by their owner. Between 2017 and 2019, the historian digitised the slave registries, thus enabling the average citizen to take a look. For this he collaborated with the Anton de Kom University in Suriname and the National Archives of both Suriname and the Netherlands, as well as hundreds of volunteers. Now Van Galen is about to take the next step: he is going to investigate the lives of former slaves after their liberation. Who did they marry? How many children did they have? How old did they become?

‘The administration of the British colonies was nowhere near as good as that of Suriname.’

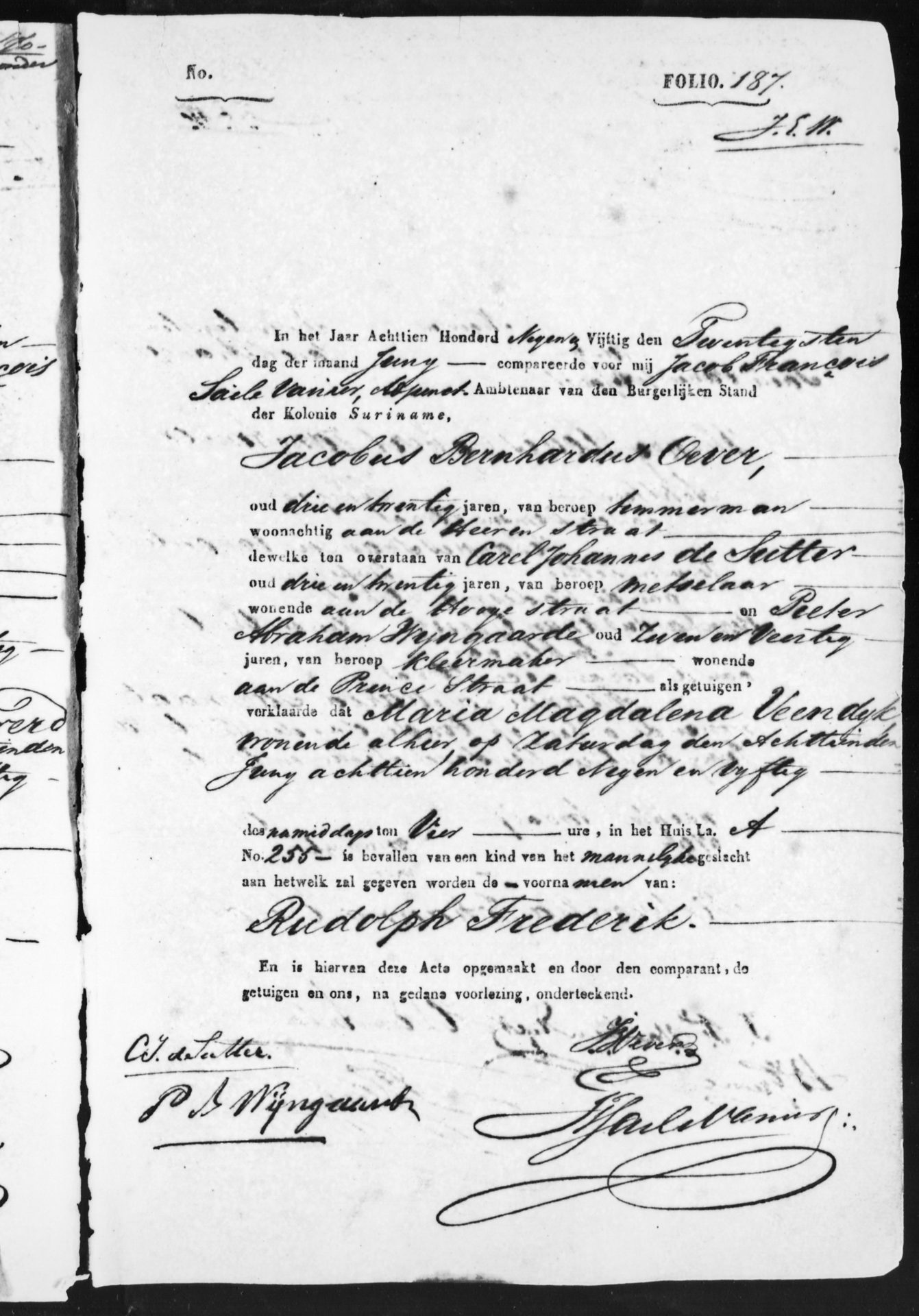

‘We are going to digitise all the historic data of the registry office,’ says Van Galen. ‘What’s unique is that, at the time, meticulous records were kept for everything. Suriname was a Dutch colony and the registry office had to be managed in the same way as the Dutch offices were.’

Because the officials at the time neatly documented everything in large ledgers, today’s researchers possess a wealth of information. ‘The administration of the British colonies, for example, was nowhere near as good as that of Suriname.’

Treasure Trove

The slave registries that Van Galen digitised previously ran up to 1863, the year that slavery was abolished. Which means that if a Surinamese person or Dutch person with Surinamese heritage wanted to investigate their roots via the internet, there wouldn’t be any information available to them beyond that date. But this will be the case in a few years, when Van Galen, his team, and all the volunteers have done a great deal of work.

However, Van Galen is not doing this research just for those people who want to know more about their ancestors. He refers to the 300.000 well-kept birth certificates, marriage licences and death certificates as a true ‘treasure trove’ for historical demographers. To quote Van Galen: ‘By collating all that information about hundreds of thousands of lives, you can really try to comprehend this kind of tropical society. You can detect patterns. How did slavery affect the future? Some people who grew up on the plantations -and thus outside the monetary economy- probably couldn’t manage to earn their own money once they had been liberated, while others did manage it. There were also some Surinamese people who elected to remain on the plantations in exchange for a salary. Where these just the elders? These are all questions we will be able to answer.’

The plantations did keep running after the abolishment of slavery on July 1st, 1863. After all, this industry was supposed to keep Suriname profitable. Other groups of people started coming to the Dutch colonies; a kind of guest workers from China, India and Indonesia, who were connected to certain plantations for several years. Van Galen calls this a ‘hybrid’ form. While slavery had been abolished and the immigrants were granted a salary, the plantation owners were still allowed to dole out punishments to employees who failed to meet their quotas, for example. Van Galen also wants to show how those groups faired over the course of time. Like the guest workers in the Netherlands, many of them stayed in their host country for the rest of their lives, and new generations came to Suriname to stake their claim.

Volunteers

For his new project, Van Galen is once again working with the Anton de Kom University in Suriname, as well as the National Archives of the Netherlands and Suriname. Two post-docs are already involved with the project, and two PHD students from Suriname will be appointed to do a part of the research. Additionally, Van Galen hopes that plenty of volunteers will offer to help, like they did for his previous project involving slave registries. At the time, hundreds of people used their home computers for data entry, in their effort to make the digital archive complete and searchable. ‘This follow-up research is another massive enterprise, that is going to take several years,’ according to Van Galen.

In the long term, Van Galen also wants to publish the data from the registry office of Curaçao. The Dutch government kept meticulous records there, just like they did in Suriname. According to Van Galen, there is a great desire among people of Surinamese or Antillean descent to know more about their families. ‘Slavery was an exceptional situation, of course. People didn’t have last names but were named after the plantation they worked on. It can be very touching for their descendants to suddenly see their near-mythical ancestors on paper; to read about where they lived. Those are small but precious mementos.’

How to help out?

Volunteers who would like to help out of house with data entry can sign in with Coen van Galen’s research team at hdsc.ning.com.