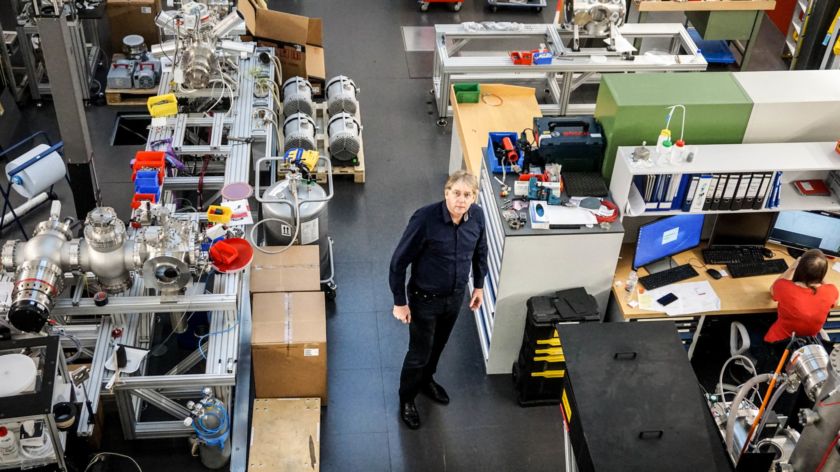

Gerard Meijer gets to mess around in the lab again

-

Photo: Annemarie haverkamp

Photo: Annemarie haverkamp

In January 2017, Gerard Meijer stepped down after four and a half years as Radboud University’s chair. He wanted to go back to research, back to his beloved Berlin. A year later, VOX pays him a visit. And finds a molecular physicist delighted to be once again ‘messing around in the lab’.

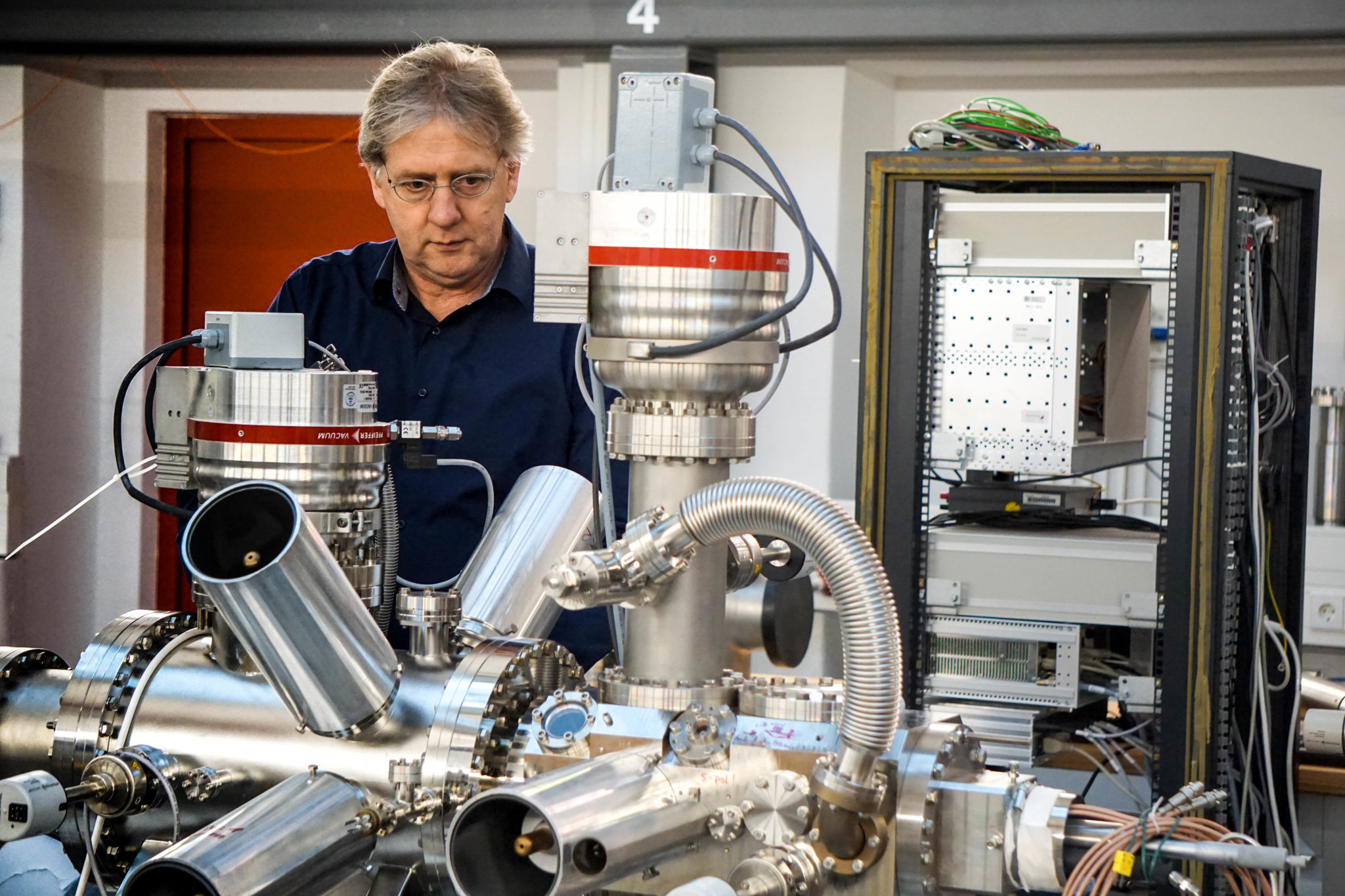

‘In the past year I’ve spent more time in the lab than in the ten years before that.’ Gerard Meijer wanders among impressive-looking equipment in a large hall. Many of these machines, intended for experiments with molecules, are partially his invention. He was also the one to screw the installations into place, together with his PhD candidates. ‘This is what I really missed these past years,’ he confesses.

‘This is what I really missed these past years’

In January 2017, the former President of the Executive Board returned to Berlin to go back to research. He became one of the five directors of the Fritz-Haber-Institut der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft, the same position he occupied before being asked to become President of Radboud University’s executive board in 2012. His German office remained, seemingly waiting for his return. He also asked his former secretary, who had retired in the meantime, to come back to work for him. ‘I had to rebuild the entire department from scratch, so I needed the support of someone who knew the institute.’ Luckily, she agreed.

The Max-Planck-Gesellschaft is organised in such a way that a department is built around a director. When the director leaves, his PhD students and other researchers have no choice but to pack up too. ‘Researchers take their equipment with them to their new workplaces. So when I came back, the whole place was empty.’

The advantage, according to Meijer, is that he was forced to think hard about what he really wanted to set up in Berlin. ‘It was a fantastic opportunity. What direction did I want my research to take? What people did I need to get on board?’

‘Isn’t it great that you can just come up with these ideas and get funding for them too?’

Meijer proceeds to show us around the Institute. To an outsider, the research he’s doing now probably looks the same as what he did before going to Nijmegen, he says. ‘Experimental molecular physics. But while we previously looked at molecules in the gas phase, we’re now focusing more on molecules in liquids.’

In one of his labs a PhD student is working on a copper machine. Among other things, the machine consists of a box, in which a smaller box is placed. ‘We close it with a kind of fridge door,’ says Meijer. ‘In this machine, we use cold helium to cool down molecules. It goes down to 4 Kelvin. At such low temperatures, molecules display different properties.’

He’s glowing. ‘Isn’t it great that you can just come up with these ideas and get funding for them too?’

Adventure

Of course he’s always known he was more of a researcher than an administrator; he even knew it when he took on his Nijmegen adventure nearly six years ago. But he thought it was too much of an honour to refuse, and above all, he was ready for something new.

‘In Nijmegen I learnt so much and I met so many people. I wouldn’t have wanted to miss it for the world,’ he says. He has no regrets. The only thing that bothered him after a while as President of the Executive Board was that he couldn’t set his own agenda. He was often booked full and spent too much time reading documents and leading meetings. ‘Here I have much more control over my time. It’s so important to have time to think! I also get to decide when I want to take an afternoon off to talk to a journalist. And if I’m away from the lab for a few days, the work goes on.’

Not that Meijer isn’t involved in ‘administration’. As a director, he’s responsible for running the Institute and for all the administrative hassle this involves. And as of 1 February, he was appointed to the German Wissenschaftsrat. ‘It’s the highest institution that advises the government and bundesländer (provincial governments, eds.) on scientific policy. It consists of 24 renowned scientists from all over the country, together with eight famous public figures.’ The topics the Council addresses are in line with the themes Meijer wrestled with as President of the University. Internationalisation, diversity. ‘My Nijmegen experience is very valuable in this regard.’

Score

One of the things people ask him frequently is how the Netherlands manage to compete at the international top even on a relatively small budget. His answer? ‘In the Netherlands people collaborate differently. The Donders Institute is a beautiful example of this. The Institute’s infrastructure is shared by a group of prominent researchers. Something like that wouldn’t happen in Germany, where every director has his own MRI and other equipment. In the Netherlands, you’re forced to share these kinds of facilities because of the lack of funds. But as a result you have to work together and you learn from one another.’

‘In the Netherlands people collaborate differently’

In his farewell interview with Vox, Meijer said he’d like to score once again. He wants to see his PhD candidates succeed, to publish articles. He’s not quite there yet. ‘This past year was spent mostly appointing people and starting experiments.’ He also moved into a house in the green neighbourhood Dahlem, home to the University of Berlin and its research institutes. He reported to his former football club – ‘even though I can’t play anymore because of a damaged knee’ and dropped in to see his former neighbours. ‘It felt like a real homecoming.’

Will he remain in Berlin until he retires? ‘I think so,’ he says as he pours his visitors a glass of water. His Nijmegen adventure taught him where his heart truly lies. He thinks he may also feel more at home in an institute with disciplines that are closer to each other and to his own. At the Fritz-Haber-Institut he’s among researchers who share his world view.

After he left, a number of his ex-colleagues referred to him as being quite blunt because of his decisive (sometimes bordering on impatient) decision-making. He’s not particularly surprised to hear this. ‘It’s something you often hear as a natural scientist. It has to do with being used to thinking rationally and linking conclusions to rational steps. You don’t spend time reconsidering a case from all perspectives. You just accept that there are laws of nature.’ He found this to be one of the most difficult things at the University: dealing with irrational people. ‘Things would happen that I really didn’t understand. At times I saw no way to break through these kinds of barriers. I was almost disappointed in myself. Why was I unable to solve it?’

He doesn’t want to go into details. And hastens to add that he really didn’t ‘mind’ being President of the Board. He often goes back to Nijmegen, and always with pleasure. He combines it with a visit to his elderly parents in the Achterhoek. He doesn’t need to come to the Waalstad to see his children: two of the three are completing a PhD in Eindhoven and Amsterdam, and his son studies at Eindhoven University of Technology.

Once the dust has settled a little in Berlin, Meijer plans to start teaching again. But first he gets to ‘mess around in the lab’, as he puts it with a wide grin. ‘I’ve noticed that I’m actually quite good at it.’