If a room looks too good to be true; online scammers remain a problem on the Nijmegen student housing market

-

Foto: Julie de Bruin

Foto: Julie de Bruin

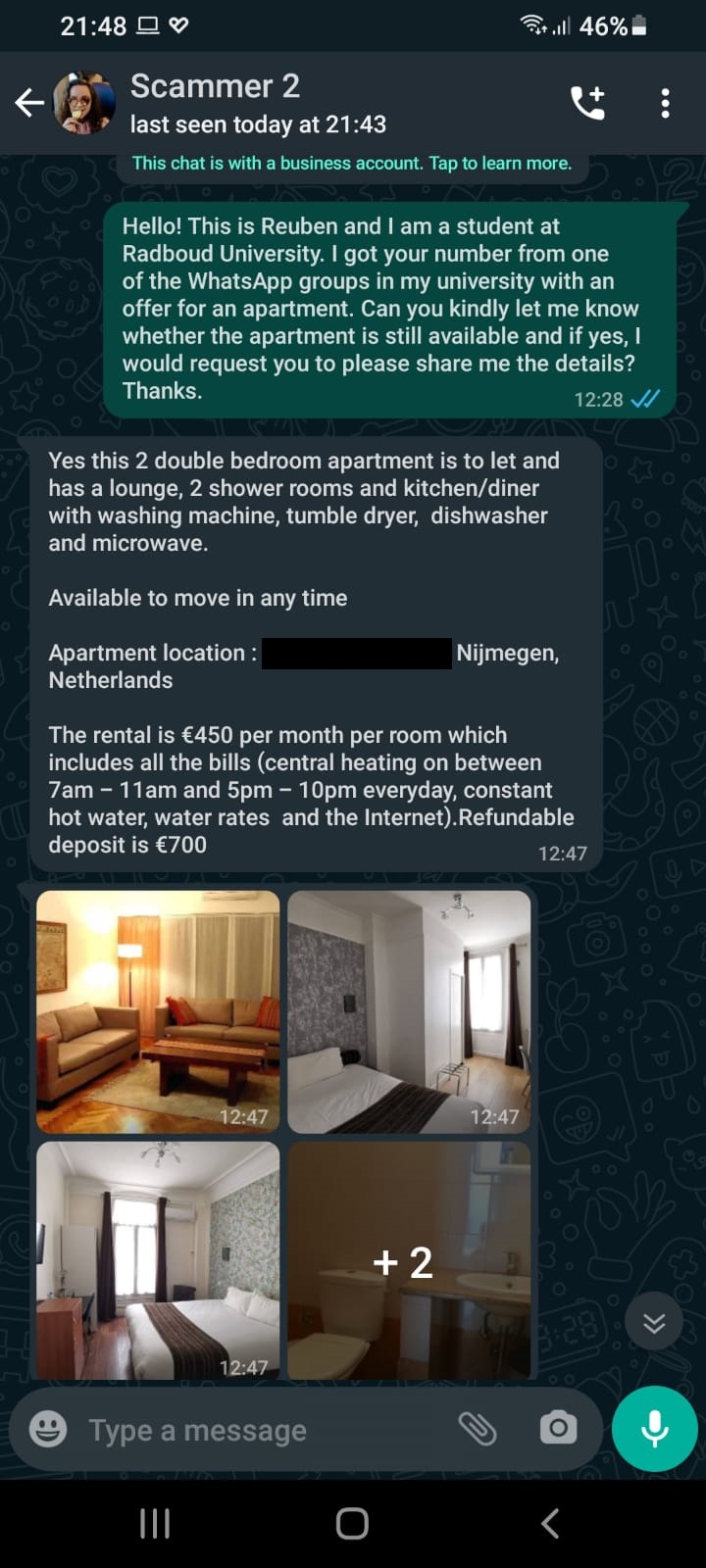

A person with a telephone number from Portugal and a claim to be based in Dublin has been offering an apartment on Facebook and in WhatsApp groups. Vox reporter Reuben Malekar posed as a house-seeker and discovered that the alleged apartment does not exist, while reporting on the reactions of the international office at Radboud University and the police of the East-Netherlands. ‘These scams are not new to us.’

The apartment looked like a dream for a house-seeking student in Nijmegen, with photographs showing shiny wooden flooring, neatly painted white walls and some glossy furniture. But the low rent and central location of the apartment seemed too good to be true.

When Vox decided to express interest in the apartment and engage in a conversation with the individual making the offer, the apartment was available, but a viewing not an option. Apparently, only a digital signing of the contract and the transaction of the first month’s rent and deposit would lead to the keys being posted through a courier service.

However, a visit to the address of the apartment confirmed the increasing suspicions: the claims about the property were absolutely false, the place shared did not exist. The current tenant, an old lady, was in shock about their address being used to trap home-seekers. ‘This is definitely not what our house looks like,’ the current renter said when shown the photographs shared by the individual making the offer.

Housing in Nijmegen

With the academic year of 2021-22 about to start, the need to accommodate students in Nijmegen is at an all-time high. However, this rise in demand stands in contrast to the lack of housing available within Nijmegen, as has been extensively reported in the past. A housing shortage that is not only a continuing, but also a major issue for the city.

Moreover, not just the population of Nijmegen, but also the number of students enrolling at Radboud University keeps increasing every year. According to the university’s web page, the total number of students at Radboud increased from 22,976 in 2019 to 24,104 in 2020. This rise in enrollments might play a major role in the imbalance on the housing market, creating an opportunity for scammers to prey on vulnerable home-seekers, especially international students who remain primary targets.

The international office

‘Scamming for houses is indeed a problem,’ says Elco van Noort, the internationalization coordinator at Radboud University. According to the international office, at least one student is confronted with scamming related problems every year. But van Noort is concerned that there might a high number of unreported cases.

According to van Noort, newcomers are most vulnerable for scams, since they cannot physically check the accommodation like students already living in Nijmegen. Which is why Radboud guarantees accommodation to all incoming international students that register for the pre-arrival services before the 1st of May.

The students in their second year of studies, however, are given no guarantees for housing. Instead, they are put on waiting lists for a potential offer. ‘We were up to 250 students on the waiting list in June and are down to 125 at the beginning of August. This suggests good progress,’ according to van Noort.

But even though van Noort is optimistic that the international office will be able to provide accommodation to the incoming students till the beginning of September, it will be difficult to cater accommodation for students in their second year of studies. In the meantime, van Noort urges students to be patient and careful of scammers.

Police of the East-Netherlands

‘These scams are not new to us,’ says Jennifer Schoorlemmer, the spokesperson of the police of the East-Netherlands. According to Schoorlemmer, scams like these are a common occurrence, not just in Nijmegen but also in other parts of the Netherlands.

But while the police of the East-Netherlands are well aware of the problem, housing scams are not exclusively a police matter, with bodies like the Netherlands Authority for Consumers and Markets (ACM) and the Landelijk Meldpunt Internet Oplichting (LMIO), the national hotline for internet fraud, also involved. ‘ACM and LMIO investigate websites that rent out houses which sometimes do not exist and also use mediums like Facebook to spread their advertisements,’ states Schoorlemmer.

Still, if one does fall for such a scam, a complaint with the LMIO and a report with the police must be filed, leading, according to Schoorlemmer, to a detailed investigation by the police.

As a preventive measure, Van Noort suggests looking at the information posted on Radboud’s web page, including a list of trusted private housing agencies and commercial accommodation agencies, amongst others that could help students find a nice place. Additionally, according to the police, students should avoid to pay upfront, at least before attending an in-person viewing of the property.