Is online education here to stay?

-

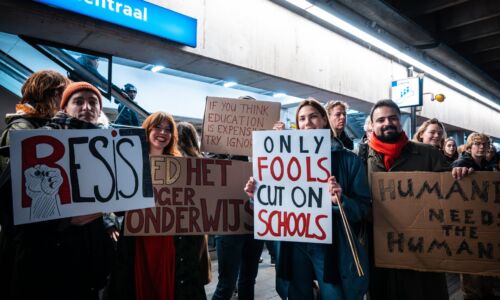

The people on the picture are not part of the story. Image edited by Gloed Communicatie

The people on the picture are not part of the story. Image edited by Gloed Communicatie

Since March, lecturers have been giving online lectures and administering online examinations. In response to the crisis, academic education had no choice but to reinvent itself. What lessons can we learn for the university of the future? Educational experts say it’s all about trust and personal contact.

‘Dear children, we miss you,’ it says in big chalked letters on the wall of a Nijmegen primary school. School teachers welcomed their pupils back in mid-May, but Radboud University will have to wait at least until September to resume Campus life. Lecturers also miss in-person contact with their students, and students miss the Campus, each other and, if they are honest, their lecturers too.

There’s no denying it: it’s been a bit of a struggle. Students miss the structure of the Campus and often find it difficult to find the self-discipline to study from home, in many cases their parent’s home. Many are anxious and uncertain about how their study is progressing. Lecturers are ‘square-eyed’ from all the Zoom and Skype calls and examinations, and in their online lectures they miss the didactic finesse of in-person contact.

‘When you teach logic, it’s nice to be able to draw something on the board from time to time. You can’t do that online,’ says Huub Vromen (Philosophy of Language and Logic). ‘Plus, on a computer screen you can’t see the students’ puzzled looks when they don’t understand something. It makes real interaction with students, but also among students, much more difficult.’

Lecturer in Notarial Law Lucienne van der Geld also misses in-person teaching. ‘I can’t wait to get the green light and stand in front of the classroom again.’

Disastrous semester

All lecturers are working around the clock to make sure classes and examinations can proceed as planned. But the result is hardly business as usual. In an attempt to replace in-person lectures, many are trying out alternatives.

For example, Lucienne van der Geld is making use of this opportunity to turn her lectures into podcasts. ‘I’ve cut them up into pieces; you can’t record 90-minute stretches. Unfortunately, I can’t see my audience so I don’t know whether what I say is coming across.’

In collaboration with the University of the Netherlands, Professor of Dutch and Academic Communication Marc van Oostendorp offers video ‘quarantine lectures’ for the general public. As online teaching continues, Van Oostendorp is increasingly disenchanted. Things are going from bad to worse, he comments in a blog post on Neerlandistiek.nl. He believes the best solution would be for Minister Van Engelshoven to give up on ‘this disastrous semester’ and grant all students an extra six months of study time. He wants the academic community to take a step back and think about what they’re doing.

‘We really have to stop and think about what we want to keep from the old and the new system’

Thinking about what Radboud University wants when it comes to teaching is precisely the task of the Radboud Teaching and Learning Centre (TLC), launched in January this year. Led by Philosopher Jan Bransen, TLC supports and stimulates Radboud University lecturers to reflect on and bring innovation to their teaching.

‘The coronavirus crisis really got in the way of this process,’ says Frank Léoné, Assistant Professor in Artificial Intelligence, and driving force of the TLC. The centre barely had time to start before it was overwhelmed with requests for practical advice on online teaching and examinations. This left little space to really think about things. But the TLC also sees the crisis as a lever for a more considered approach to academic education.

Léoné: ‘Why for so long have we been teaching lectures and administering examinations? What is our vision on how to design education?’ Paulien Meijer, Scientific Director of Radboud Teachers Academy adds: ‘We really have to stop and think about what we want to keep from the old and the new system.’

Nervousness

An important source of friction in these coronavirus times are examinations. Students are overwhelmed by the number of examinations and tests and the accompanying stress. Nicolo de Groot, Vice Dean of Education of the Faculty of Science understands that people are more nervous than usual.

‘It’s a very stressful period for everyone, students and lecturers alike.’ The bête noire these past months has been online proctoring: a system of remote examination supervision for large groups, using a webcam and microphone. The SP has asked questions about it in Parliament, and in Nijmegen student representatives on the Student and Works Council have expressed grave concerns about this kind of online surveillance. The system raises a dilemma: how much privacy should students give up to avoid study delay? Students are denouncing the system for not only monitoring sound and image during an examination, but also recording every single mouse click. Anything to avoid examination fraud.

Chair of the Nijmegen Student Council Hans Kunstman called on the Executive Board to carefully consider the balance between fraud prevention and privacy. ‘We see the need to prevent study delay, but proctoring encroaches deeply on the students’ privacy.’ Kunstman also questioned how fraud-proof the system actually was, a concern that intensified when researchers at the Nijmegen Digital Security department effortlessly bypassed the examination system. In response to the commotion, the Executive Board has requested an investigation and promised that the system would only be widely used if privacy can be guaranteed.

Scrap heap

Aim for trust rather than control, says the Teaching and Learning Centre in its advice to the Executive Board concerning examinations. Meijer and Léoné are ready to move away from the ingrained mistrust at the heart of the educational system. And this applies both to university and secondary education.

‘I hear from school pupils that they feel more controlled than ever,’ says Meijer. All cameras must be switched on at all times, and there’s no escaping the teacher’s gaze. ‘We always teach our students: the way you approach your pupils is the way they will behave. You can come up with all kinds of regulations to stop students from cheating, but this will only encourage them to find more creative ways around it.’

‘Having to spend 90 minutes looking at a screen with a talking head is really incredibly boring’

Jan Bransen also has an aversion to surveillance. ‘Why do we it, actually? Why are lecturers and students stuck in this cat-and-mouse game, while other educational activities require them to work together towards a common goal?’

Turn it around, says the TLC. ‘Putting pressure on students during examinations to make sure they don’t commit fraud doesn’t contribute to a safe learning environment, and therefore also not to learning,’ says Léoné. In their recommendation, he and his colleagues look further ahead, to the question of why we test in the first place. ‘All professional literature on the subject emphasises the importance of formative testing: testing as a learning moment for the student rather than an assessment: improve rather than prove.’

Broken cameras

Now that all teaching takes place online, it is becoming all the more clear which areas are in need of improvement. ‘Having to spend 90 minutes looking at a screen with a talking head or watching slides is really incredibly boring,’ says Léoné. Like many other lecturers, he prefers to cut his lectures into shorter videos.

Once the coronavirus crisis is over, it would be a good idea to reconsider the format and role of lectures. ‘Lectures are often poorly attended and research shows that they’re not very effective for those that do attend them anyway. So why devote so much time to them?’

Meijer hears similar things about secondary education from her students and her two teenage daughters. ‘When the lessons get too boring, microphones and cameras suddenly stop working.’ Making lectures more fun with flashy videos or, once the coronavirus crisis is over, with other kinds of enhancements, is not necessarily the way to go, warns Meijer.

Creative

‘In our research programme, we distinguish between teaching creatively and teaching for creativity: creative teaching doesn’t automatically lead to school pupils and students being more creative, or even learning. If we want to teach students to think critically and solve problems, we should perhaps switch to minimal teaching. We have to reconsider the relationship between how we teach and what and how students learn.’

As far as she’s concerned, traditional timetables, with a subject every hour, can also go. ‘For instance, we could spend one classroom hour per week on a subject, leaving more time for collaboration in small groups and more freedom for pupils to choose when to work on what.’

Personal contact

One frequently heard remark is that lecturers now finally understand the usefulness and necessity of ICT and are catching up fast in this domain. This is a good thing to maintain once the lockdown is over, but no one is in favour of remote teaching alone. Keep what is useful and value personal contact, says Léoné: ‘In this context, you should think carefully about where and when social contact is essential in teaching. For example, I’d like to continue to run my work groups in person, but I wouldn’t mind replacing my lectures with short online videos.’

For Jan Bransen, one of the lessons of this period is the need to replace ‘largely ineffective’ lectures with knowledge clips and video lectures. ‘This will allow us to use our teaching hours to explore the subject in more depth.’ But as with all innovations, says Bransen, it’s essential to retain the heart of teaching: seeing each other in person.

Lucienne van der Geld appreciates contact during breaks and before and after lectures, also among students. ‘We are now discovering how important this is.’ Personal contact promotes learning. Meijer refers to a study by one of her PhD candidates on the importance of social presence. ‘Those moments when the penny suddenly drops for students: ‘‘Wow! That’s how the world (or this field) works!’ only happen when they’re physically together with other students and the lecturer is actively engaging with a subject.’

This kind of contact is not only crucial for students, but also for teachers. As Meijer recently heard a lecturer say: ‘I’ve never put so much effort into preparing my lessons and got so little satisfaction from them’. ‘Satisfaction comes from contact with pupils and from watching them learn.’

Léoné agrees completely: ‘There’s nothing so satisfying as seeing that the knowledge I’m trying to convey actually goes in.’ As care for one another grows across society, lecturers are more than ever concerned about their students’ wellbeing. They frequently ask how everyone is doing, and whether they are still managing.

Meijer: ‘I hope this kind of attention remains. It’s infinitely more conducive to learning than this constant pressure to perform, and it makes for a much nicer university for everyone.’

Teacher in training: ‘It’s like having an office job’

Last year Roel van Koeverden (24) completed his mathematics teacher training and he is currently training as a teacher in business economics at the Radboud Teachers Academy. The coronavirus has transformed his internship at the Nijmegen Dominicus College beyond recognition.

‘I’m now discovering all the things you can do with ICT in teaching. It’s very instructive. But classroom management, keeping order and making sure pupils are working, isn’t something you can learn this way. It actually requires being in a classroom and seeing people’s faces.’ At the moment, he also only teaches small groups of pupils. ‘It’s completely different from having an entire class to keep in check. The contact with pupils is also different; it’s kind of second-rate communication.’

Van Koeverden spends his internship days at home typing texts at his PC, video calling with pupils, and working through his e-mails. ‘I’ve suddenly got an office based job, while what I love is walking through a classroom, and making jokes with my pupils. It’s all very dry now.’ His study programme is also much less fun. ‘I used to really look forward to contact with my fellow students. That’s all gone now. I spend all my time at my laptop; it’s no fun anymore. I’ve been a student for six years, and now my student life is going to just fizzle out.’

This article was published before in the corona special made by Vox and Radboud Magazine.