‘It’s scary to think they’re working inside your head’

Coen Cieraad suffers from Parkinson’s. The disease makes it increasingly difficult for him to move. Radboud umc (Radboud university medical center) offers an operation that may relieve the symptoms: deep brain stimulation. VOX is invited to attend the brain operation. ‘No, there isn’t enough room here. We run the risk of hitting a ventricle.’

Beep, beeeeep, beep. A loud screeching sound fills the room. If you didn’t know better, you might think these were alien signals. Yet these aren’t sounds from a planet in some far corner of the galaxy, but from inside our own inner world: the brain. The beeps originate from an electrode that neurosurgeon Saman Vinke (33) is guiding one millimetre at a time into the brain of Coen Cieraad (69).

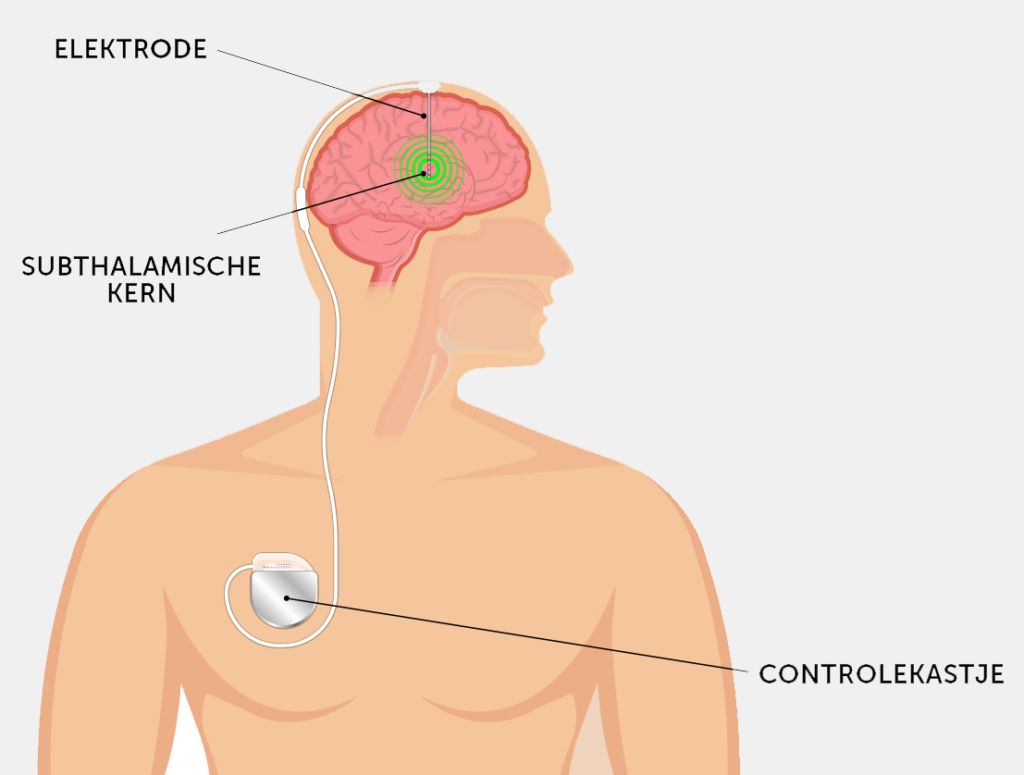

Cieraad suffers from Parkinson’s disease and on this November morning he’s undergoing what is known as DBS, short for Deep Brain Stimulation. This operation involves inserting two thin wires called electrodes approximately 8 cm deep into the patient’s skull, where they stimulate a small peanut-shaped region of the brain. This area, known as the subthalamic nucleus, plays a key role in movement control, from walking to grip. In Parkinson’s patients, this nucleus is overactive, which makes walking difficult. Small electric impulses help stabilise the subthalamic nucleus.

Sense of smell

It’s been almost twenty years since Cieraad experienced the first symptoms, explains the soft-spoken Apeldoorn inhabitant the day before the operation in the mini-library of the neurology department. In was in the spring of 1999. ‘The garden was in full blossom and my wife Tineke said: come and smell the flowers! But I couldn’t smell a thing.’ An impaired sense of smell is often one of the earliest symptoms affecting a majority of Parkinson’s patients.

Looking back, it was a clear sign, but at the time no one thought of Parkinson’s. Nor did any alarm bells go off when Cieraad started to sway when walking a few years later. In the end, it was the retired engineer’s brother-in-law who finally noticed him walking strangely, which got the ball rolling. ‘We made a list of all my symptoms and showed it to our GP. All of a sudden, it was clear as day.’

One reason Cieraad was diagnosed so late is that he didn’t suffer from tremor, the ‘classical’ shaking of the hands that affects approximately 50% of Parkinson’s patients. In Cieraad’s case, the disease primarily manifested as slowness and stiffness. ‘You develop different strategies to deal with it, like jumping up and down to get moving.’

The symptoms are not only uncomfortable; they can be quite dangerous, as Cieraad discovered for himself. Shortly before his diagnosis, he fell down stairs a few times because his legs refused to work. And he once almost got run over by a car – stopping moving can be as difficult as starting up.

Brain stem

Parkinson’s disease involves the progressive dying off of nerve cells in the substantia nigra, a black-coloured nucleus in the brain stem. This nucleus produces dopamine, a signalling agent that plays a key role in controlling movement, but also in emotion regulation. With too little dopamine, it becomes harder to control hand and foot movements. Patients may also experience changes in cognition, mood and behaviour, such as difficulty planning, slower thinking, depression and reduced initiative.

At first, Cieraad was able to regain his mobility thanks to levodopa, a medication that restores depleted levels of dopamine in the brain. These days he has to take a pill every two hours and wear a medication patch with another drug that’s absorbed through the skin. He and his wife plan their day, from mealtimes to visits, around this strict medication regime.

Now the disease has progressed so far that it no longer makes sense to increase the medication dose: the side effects are becoming too severe. Cieraad suffers from dyskinesia – constant physical restlessness, wriggling and shaking. ‘It’s incredibly tiring, but I’m lucky because I don’t get it at night.’ At the same time, the periods when the medication stops working are increasing in frequency and duration. ‘Then I suddenly feel like an old man.’ These developments have made him eligible for another treatment option offered at Radboudumc: Deep Brain Stimulation.

Conscious decision

DBS is one of the last options for relieving Parkinson’s symptoms without drastic side effects, explains neurosurgeon Vinke (see Box) in an interview with VOX two weeks before Cieraad’s operation. Vinke is accompanied by neurologist Rianne Esselink, Head of the Nijmegen DBS team.

Besides Esselink and Vinke, the team includes lots of other specialists: a psychiatrist, a social worker, a radiologist and an anaesthetist, as well as neuropsychologists, OR staff and a specialised nurse.

Esselink emphasises that patients and their relatives are deliberately involved in decision-making. ‘I always say: it’s an intervention we perform together; patients and their family are part of the team. For me, optimal care for Parkinson’s patients means informing them in detail about the options available.’ For example, one alternative to DBS is a drug pump that administers levodopa directly into the small intestine. ‘People who make a conscious decision are usually more satisfied in retrospect – even if the treatment turns out to be disappointing.’

Face mask

Tuesday morning, 12 November. In OR 4, Vinke, wearing green surgical gloves, holds a shiny 45 cm wire from which protrude other, thinner, wires. On their tips are four tiny dots – two single and two triple electric contact points, eight stimulation points in total.

Fine-tuning will only take place two weeks later, once Cieraad has recovered from the operation. Now the electrodes are switched off, and the focus lies on implanting them as precisely as possible. Under full anaesthesia, of course. Up until last summer, Nijmegen patients were awake during DBS to allow the surgeons to control brain functions like speech. The team discontinued this practice when it became apparent that the operation method was so precise that MRI and CT scans sufficed. Plus, it’s much more comfortable for patients to be asleep, and operations now only last four hours instead of seven.

8 a.m. ‘Think of something nice,’ the anaesthetist tells Cieraad in the OR as she adjusts a face mask with a sedative over his mouth. ‘You’re in safe hands.’

Vinke – short stature, dark curly hair, open expression – gets to work. He carefully disinfects Cieraad’s head and screws on a blue zigzag-shaped frame, straight through the skin and into the cranial bone. He’s assisted by his colleague, Ronald Bartels, Professor of Neurosurgery. In principle, one surgeon can do the entire DBS operation, explains Vinke. ‘But I wouldn’t advise it. It’s good to be able to double-check everything.’

The next step is an MRI scan. The zigzag frame can be seen on the brain scans appearing on a computer screen in the consultation room. It forms a point of reference for attaching the device that will direct the electrodes, explains Vinke. ‘We use it to create a kind of map of the brain.’

‘Think of something nice,’ says the anaesthetist

Together with Esselink and Bartels, the young neurosurgeon decides where to insert the electrodes to reach the subthalamic nucleus without problems. It’s a bit of a puzzle. ‘No, there isn’t enough room here; we run the risk of hitting a ventricle. Can you move it a bit backwards? Yes, now we’re a couple of millimetres from it; that’s good.’

Ventricles, filled as they are with cerebral fluid, should definitely be avoided, but so should blood vessels. If things go wrong, the result may be a life-threatening brain haemorrhage. ‘That’s never happened in one of my operations,’ Vinke immediately reassures us. ‘It occurs at most in 1% of cases.’ After ten minutes, Vinke notes the target location (‘x: 86.6’) and the angles the electrodes have to negotiate.

Vinke has now performed approximately seventy such operations. He acquired his expertise at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London. ‘Highly motivated and talented,’ is how an operation assistant describes him. At Radboudumc, the surgeon was involved in setting up the DBS centre.

Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS)

In DBS, the subthalamic nucleus is kept in check by electric impulses, just like in a heart pacemaker. In Parkinson’s patients, this region of the brain becomes overactive as a result of a dopamine shortage – leading to slowness and stiffness. Neurosurgeon Vinke: ‘Think of it as driving a car while constantly hitting the brakes.’

Not all patients are eligible for DBS, explains neurologist Rianne Esselink. ‘Patients must be 75 years old or younger, have been diagnosed at least 4 years previously, and experience fluctuations in medication effectiveness throughout the day, including times when medication doesn’t work, and dyskinesia. At the same time, they must still be responsive to medication, since they will need to continue taking it after DBS.’

Last year, Esselink and her team started offering DBS at Radboudumc, in close collaboration with the Maastricht University Medical Centre. At the time, the operation was only performed in a few other locations in the Netherlands. ‘Nijmegen is a logical place for DBS, as we’re known for our extensive expertise in Parkinson’s disease.’

Nijmegen created the DBS centre in response to a long waiting list for the operation after a scientific study revealed that patients could benefit from DBS even in the early stages of the disease. Radboudumc now operates on approximately 40 Parkinson’s patients a year and plans to increase this number to 60 in the coming year.

A strand of spaghetti

Thirty minutes later, back in the OR. The surgeons attach a metal arc to the zigzag frame, similar to the arc on a globe. Yellow numbers and dashes line the edge. Attached to the arc is a sliding titanium cylinder with a one-millimetre hole in the centre, through which the electrode will be guided with great precision to the right location. Vinke marks with a dot the spot where the electrode will enter Cieraad’s skull (top left), before slicing the scalp open all the way to the bone.

‘Z 117.2?’ ‘Z 117.2!’ Vinke and Bartels check the coordinates one last time.

A drill the size of a large electric toothbrush slowly makes its way through the patient’s skull. When it stops, you can see the outer grey-white brain membrane (dura mater) through a hole exactly fourteen millimetres in diameter. A small blood vessel that runs straight across the membrane is cauterised on both sides.

A minute later Vinke slides the electrode into the brain, as cosmic beeps resonate through the OR. The pitch of the sounds helps the surgeon identify which brain areas he’s passing through – cerebral cortex, capsula interna, thalamus – before the electrode reaches its destination. A high tone indicates high conductive resistance, which means the electrode is moving through white matter, the connections linking different regions of the brain. Cerebral nuclei – grey matter – generate low tones.

The electrode’s journey causes minimal damage to nerve cells, explains Vinke: ‘It’s a bit like trying to pierce a single strand of spaghetti with a fork: not likely to happen.’ The patient also suffers relatively little external damage: three small wounds (from 0.5 cm to 10 cm) are the only reminders of the operation.

Fifteen minutes after the electrode has been positioned, it’s followed by a second one, this time in the upper right-hand area of the skull. Small plastic plugs under the skin are used to close the openings and keep the electrodes in place. The surgeons push down the wires sticking out from Cieraad’s head under his skin all the way down to the right clavicle. It’s not easy with all the muscles and tendons. ‘That was hard,’ Bartels sighs when he finally succeeds after a few minutes.

‘The disease continues to progress, but I’ve been given a reprieve.’

This fiddling under the skin is essential. It makes for a more aesthetic result and – more importantly – prevents infection. The device stimulating the electric impulses is also implanted in the body. Vinke places it under the chest skin. The stimulator’s batteries can be charged remotely, like charging mats for mobile telephones.

We’re almost done, but the team still has to check that the electrodes are positioned correctly. To find out, the OR staff bring a still-sedated Cieraad back to the CT scanner.

Bartels colours the electrode dots on the CT scan green and places them over the first MRI. The coloured dots appear at the bottom of the subthalamic nuclei – exactly as planned. Bartels calls Vinke to confirm that there’s no need to go back to the OR. It’s 12.15 p.m. Cieraad can be moved to the recovery room. The operation was successful.

Fine-tuning

As he leaves the hospital two days later, Cieraad sounds mostly relieved. ‘It’s scary to think they’re working inside your head. And what if you’re the 1% that goes wrong?’ All he feels is some pain on the top of his head, but it’s easy to control with paracetamol. He has no recollection of the operation.

But Cieraad knows that the hardest part is still to come: fine-tuning the electric stimulator. In two weeks, he’s expected in Nijmegen to start the treatment, which can last up to six months. And even if the DBS is perfectly calibrated, he’ll still need his Parkinson’s medication, albeit a lower dose than before. ‘DBS is no magic bullet,’ Vinke told us earlier.

But Cieraad can expect his quality of life to improve – and that’s the most important thing as far as he’s concerned. The small overactive nuclei on both sides of his brain can stabilise, without side effects like dyskinesia. Cycling, walking and visiting friends should all become easier than they were. ‘It’s all about winning time. You can’t turn back the clock – the disease continues to progress, but I’ve been given a reprieve.’

Do you want to know more about brains? Soon the new Vox about will be out. This article is in it too. Subject: brain.

50,000 patients

There are currently over 50,000 Parkinson’s patients in the Netherlands, according to figures by ParkinsonNet. This national network, originally established in Nijmegen, unites healthcare providers specialising in Parkinson’s disease. The number of Parkinson’s patients is increasing by approximately 4% a year, partially due to the ageing population. This makes Parkinson’s the second most common neurodegenerative disorder in the Netherlands, after Alzheimer’s.

Parkinson’s disease cannot be cured, although the symptoms – which worsen over time – can be controlled with medication. The best treatment differs from patient to patient: there’s no panacea that works for everyone. The life expectancy of Parkinson’s patients is not shorter than average, although they are at increased risk of developing other neurological diseases like dementia.