‘Nationality is hardly an issue here’

-

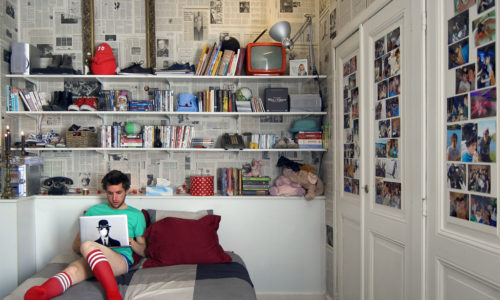

Foto: Harry Heuts

Foto: Harry Heuts

How international should Radboud University become? The various faculties, the International Office, and the Executive Board are currently discussing how international our university should become. At Maastricht, the most international university in the Netherlands, internationalisation is barely a topic of discussion.

A brief introduction to European integration: in the cafeteria of the School of Business & Economics, three students are sitting around a table. They are speaking English, yet their accents betray their different backgrounds. Each of the three has a different nationality. Evi Heeren is Dutch (but lives in Belgium), Friederike Färber is German, and Alexandra Beeler is half British and half Swiss. However, Heeren tells us that nationality does not play a significant role in their degree programme. ‘Sometimes, we don’t even know where our fellow students come from,’ says the Dutch student. ‘Nationality doesn’t matter to us.’

‘Sometimes, we don’t even know where our fellow students come from’

Welcome to Maastricht University: the most international university in the Netherlands. In 2016, no less than 51 percent of the students were non-Dutch. Even when it comes to absolute numbers, there is no other place in the Netherlands where so many foreign students are studying than in this city in South Limburg: nearly nine thousand. By comparison, this number is just over two thousand in Nijmegen. Now that Radboud University is looking into what it wants out of internationalisation, Maastricht is an interesting case study of how it could be.

Another way the two universities differ: Maastricht University is young—Princess Juliana signed for its founding in 1976. ‘That makes it a university without a past steeped in tradition’, says Jurgen van Heertum. He represents the student association Novum in the university council and studies medicine—he previously completed a study programme in Law in Maastricht as well. ‘I think that’s why we may be less trapped in fixed ways of thinking. When I started here four years ago, the university was already very international and has only become more so since.’

Future

How international does Radboud University want to be in 2025? The International Office is going around asking the faculties this question since last summer. Several discussions and workshops address the different aspects of internationalisation. The International Office collects input this way, which will be used to write a plan for the period 2018 – 2025. More information can be found here (for students and employees).

Those who walk around the Maastricht campus will instantly notice the conversations between students, street signposting, and the signs in the student restaurant. They are in English or bilingual, but never just in Dutch.

Five years ago, Van Heertum chose Maastricht because of its international character. ‘Here, you learn how to interact with people from different backgrounds and cultures’, he says. ‘That also happens because of the problem-driven style of education Maastricht University is known for. We work in small groups that collaborate intensively for roughly two months. There are many different nationalities in groups like these, so you learn a lot from it.’ He tells us that 40 percent of the academic staff is international, too. ‘This means there’s a good chance that English criminal law is being explained by a British lawyer and not by a Dutch person trying to explain it in broken English.’

Selection

Medical student Van Heertum is not the only one who chose Maastricht out of the desire to come into contact with international students and academics. Aisling Tiernan tells us this is equally true for the academic staff working at Maastricht University. She is a senior policy officer and makes recommendations to the executive board regarding internationalisation. Where Nijmegen has an International Office set up for this task, there is no such organisation in Maastricht. ‘Internationalisation is embedded into the faculties and institutes for us.’ Maastricht approaches this in its own way: everyone is working on internationalisation—it is not limited to a single office.

Tiernan, who comes from Ireland herself, rarely comes across students or staff members looking to put a stop to internationalisation at the university. ‘Students and academic choose Maastricht because it’s so international. That’s true for me too, by the way.’ Maastricht’s location near Germany and Belgium helps, but it is of secondary importance. ‘You’ll notice that our students also come from the US, China, and Brazil.’

She calls it a strategic approach: ‘We want to be international.’ Even early on, in the beginning of the 1990s, the university began offering education in English on a small scale. This got people used to it and resulted in the current high-quality level of English-language education.

Slumlords

Pepijn Poels and Tobias Klein, a German student, are sitting in the large ISN Maastricht office, which has a ping pong table, a bar, and relics from former festivities. The students are members of the ISN board, part of the international Erasmus Student Network (ESN), and assist international students in all kinds of ways. One example is the buddy system. ‘International students can apply for a buddy before they even come to Maastricht’, says Poels, the chair. ‘They are assigned a mentor who helps with practical matters, like getting a SIM card or requesting a public transportation chip card.’ ISN also organises an Arrival Week, the week after the university orientation, also called the ‘Incoming Week’. Poels: ‘Many international students miss the Incoming, so they can get acquainted with the city during the Arrival Week.’

According to the students, are there absolutely no more problems with the university becoming increasingly more international? Tobias Klein thinks it over for some time. ‘The only thing I can think of is housing for international students. They do not know what normal prices are here, so they are easy prey for slumlords.’ Klein tells us that this also has an irritating side effect: the average rental prices in the whole city are on the rise. You can find the opposite as well: landlords who do not want international students in their properties. ‘A friend of mine was unable to find a room until November and now lives in Belgium.’ According to Poels, there is also a need for more rooms for students who stay in Maastricht temporarily. ‘Many exchange students are currently staying in hostels. There is a guest house with 500 spaces and it’s always full. Currently, there are plans to add 200 spaces there.’

Poels and Klein note that there are minor problems with internationalisation: it continues to be difficult to get Dutch and international students to mix. Poels: ‘During the Incoming, mentors sometimes still try to get the international students to participate in international groups, and get the Dutch students into the Dutch groups.’ They shouldn’t really be doing that, but Poels understands it: ‘The mentors during the Incoming are active in student associations, but they are still not all that international.’ However, even life in student associations is changing. On 11 October, the Maastricht University publication Observant, wrote that the student rowing association Saurus and the student association Koko are welcoming more and more international students.

Language course

Jurgen van Heertum, a member of the student council, also sees some areas for improvement when it comes to internationalisation. ‘We are currently busy with language policy for non-academic staff, so that the level of English is increased in this group as well. We would also like to see the level of the basic Dutch course be raised in the future and it would be nice if Dutch students could also take a language course to improve their French or German, for example.’

Van Heertum thinks the percentage of international students is currently ‘in a great place.’ ‘There is no target percentage, so it doesn’t have to be 50/50. However, as a university, you shouldn’t tip too far in one direction’, he says. ‘For example, if only ten percent of the students were Dutch, that would seem pretty low to me.’ According to policy scientist Tiernan, the university is happy with the balance between Dutch and international students in Maastricht. ‘The atmosphere is good. The international community lives.’

Still, Maastricht University has some wishes. More of the international students should stay in the Netherlands, preferably in the region South Limburg. Now, the university is still educating students for other countries, and for the western part of the Netherlands. ‘What we see now, is that 23 percent of our international students stays in the Netherlands. It would be nice if we could connect these people to our region for a longer period. Students should at least have the possibility to stay.’