Nijmegen administrators and residents benefited from slavery

-

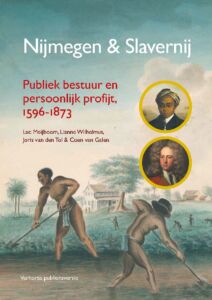

Presentatie van het boek. Van links naar rechts: Coen van Galen, Lianne Wilhelmus, Hubert Bruls, Luc Meijboom en Joris van den Tol. Foto: Paul Rapp

Presentatie van het boek. Van links naar rechts: Coen van Galen, Lianne Wilhelmus, Hubert Bruls, Luc Meijboom en Joris van den Tol. Foto: Paul Rapp

Nijmegen administrators and residents benefited from slavery for several centuries. That is the conclusion of a Radboud University research study into Nijmegen's colonial slavery past. Moreover, the current university campus is located on the former property of a Dutch East India Company (VOC) administrator, former mayor Adam Jacob Smits.

Not a lot of research had been done on Nijmegen’s slavery history, Nijmegen historians Coen van Galen and Joris van den Tol concluded when asked by the municipality to investigate Nijmegen’s colonial past.

Together with junior researchers Lianne Wilhelmus and Luc Meijboom, they studied the interests and positions held by Nijmegen administrators between 1596 and 1873, revealing a strong connection with the colonial economy and associated slavery. This led them to write a book that is now available in open access. The abridged public version will be distributed around the city.

Nijmegen oligarchs

‘You have to see the administration in those days as kind of oligarchs,’ explains Joris van den Tol. ‘The mayor and council promoted their own economic interests and those of their families through administrative positions.’ Even though Nijmegen was landlocked, the city did play an important role in colonialism, says Coen van Galen.

‘Nijmegen was the most important city of the most prominent region of the Dutch Republic. This enabled the city to put forward chairs of committees in the States General and administrators for the VOC and WIC.’ The governors were administrators within the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and the Dutch West India Company (WIC), acting as a link between the States General and these trade organisations.

Sugar mills

Lacking biographical information on the Nijmegen administrators, the researchers delved into minutes and trade information. There they found, for example, records of sales of oxen and timber to the WIC and VOC. ‘Wood was used for the ships and oxen were shipped to the plantations to power sugar mills,’ says Van den Tol.

‘Oxen from Nijmegen were shipped to the plantations to power sugar mills’

‘Nijmegen was a transit city. Goods landing in the western Netherlands were transported to Germany via Nijmegen. And the same applied vice versa for exports.’

‘This made it possible for Nijmegen to develop a processing industry, adding value to goods in order to re-export them for more money. For example, we find French refugees starting a cloth trade in Nijmegen and being helped by the municipality to child labour from orphanages.’

Pamphlets against the abolition of slavery

Slavery was not questioned in the city, Van Galen observed. ‘There was some debate about it within the Republic, especially during the Eighty Years’ War, but we found no evidence of this in Nijmegen.’ Joris van den Tol: ‘On the contrary, in the Nijmegen newspapers and pamphlets, you find articles opposing the abolition of slavery, and it is clear from the coverage that everyone knew what was happening in Suriname down to the last detail.’

Nijmegen residents were aware of what was happening in Suriname

Enslaved people were also to be found in Nijmegen. They were brought to the city by people who moved to Nijmegen from the colonies. Since slavery was banned in the Netherlands, they were officially free, but it is questionable whether they knew that. There are at least three known cases of enslaved people in Nijmegen. One of them was a man called Sedin who came to Nijmegen from the Indonesian island of Madura as a servant of the Van der Zwaan family.

Economic interests

Renowned regent families such as the Singendonck, Sweers, Engelen, and Swaen profited from the economic activities surrounding slavery, and had shares in colonial plantations. The researchers felt it was important to show this interconnectedness. ‘This offers a different take on Nijmegen’s history, one that will hopefully be taken further in future,’ says Coen van Galen.

The researchers’ book is full of examples of Nijmegen’s political and economic interests. But also of Nijmegen residents who went off to try their luck in the colonies. Some in high positions, others as soldiers. There even appears to have been a VOC ship named Nijmegen, which sailed to Asia but was shipwrecked just before returning to the Netherlands.

Heyendaal estate

The study also provided a geographical link to the university campus. Adam Jacob Smits (1685-1742) was alderman (administrator) in Nijmegen for almost 30 years and mayor twice. He was also a governor in the WIC and VOC on behalf of Gelderland. He invested in the companies and even managed to have one of the company’s ships, Heerlijkheid Horssen, named after him. Smits also owned Heyendaal estate, which he expanded with heathland and forest. The area currently houses the campus and hospital.

The research study offers starting points for much follow-up research. The activities of the former mayors, as well as the role of the nobility on the whole, could be investigated further, says Van Galen. He concludes: ‘And I am of course curious to hear the city historians’ response to this book.’

The research study was handed over to Mayor Hubert Bruls on Wednesday evening, 19 March. ‘The study’s conclusions are poignant. It’s heart-wrenching to hear what people did to each other, also people from our city,’ Bruls said in a press release. A lecture and discussion on colonial slavery will be organised for residents later this year.