Philosopher collects witness testimonies about Theresienstadt concentration camp: ‘Lessons in life from the school of loss’

-

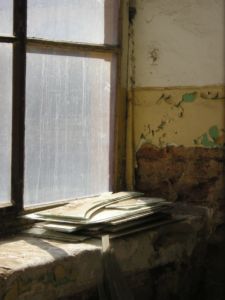

De Hamburger Kazerne in Theresienstadt. Foto: Ria van den Brandt

De Hamburger Kazerne in Theresienstadt. Foto: Ria van den Brandt

In a new book, philosopher Ria van den Brandt reconstructs life in Theresienstadt concentration camp, based on interviews with Dutch survivors. ‘My goal was to do justice to the witness testimonies.'

The idea for the book came slowly, as philosopher and researcher Ria van den Brandt tells us in her room on the seventeenth floor of the Erasmus building. In 2009 and 2010, for a project in collaboration with Memorial Centre Camp Westerbork, she interviewed Jewish people who had been deported from the Netherlands to Theresienstadt during World War II.

‘I noticed that there has been very little written about Theresienstadt in Dutch literature about the war’, she says. ‘The more I learned about that camp, the more I became aware that there was a gap in our collective memory.’

Job satisfaction

Van den Brandt decided to give the Dutch survivors of Theresienstadt a voice by interviewing extra witnesses. Together with Guido Abuys of Memorial Centre Camp Westerbork, she collected 43 witness testimonies out of the total of five thousand Dutch Jewish people who stayed in the concentration camp located in what is now the Czech Republic.

The result is the hefty volume ‘Ik was mijn houvast helemaal kwijt‘ (I lost my sense of self completely, ed.). In twelve lucid chapters, Van den Brandt sketches the memories Dutch Jews have of the transport to Theresienstadt and their arrival there, the work and the cultural life in the camp right up to their liberation.

Despite the sombre subject material, the philosopher has never felt as much job satisfaction as she did while writing this book, she tells us. ‘While I was writing the first chapters, the story gradually took on its own power and dynamics, through the voices of the witnesses. It sounds sentimental but it was as though those interviewed had taken over the story from me during the writing. I wasn’t telling the story, they were.’

What was your goal with this book?

‘I wanted to give the Dutch witnesses of Theresienstadt concentration camp a platform. After working out the 43 interviews, I started putting the puzzle together so that the various voices could complement each other – or sometimes contradict each other too. I positioned their voices next to each other, and mixed them up, like a conductor, until a substantial polyphony was created, close to the history experienced by the witnesses.

Survivors and their children who have read the book tell me that it enriches and complements their personal stories or that of their parents. They can now place their own memories in a greater whole. For me, it’s important that the book signifies actual added value for them.’

What type of camp was Theresienstadt?

‘A transit camp, or transit ghetto, from which 88,000 people were taken on to other camps. Compared to those other camps, Theresienstadt is at the bottom of the ‘misery ranking’. It was falsely presented by the Nazis to the outside world as a model camp; it looked like a real town. Many of the people who were deported to Theresienstadt were very talented. There was a rich culture in the camp; readings were organised and Verdi’s Requiem and the children’s opera Brundibár were performed. People who were in other camps later say that Theresienstadt was bearable in comparison. However, it was still a concentration camp. There was hunger, sickness and much suffering. It was a horrible camp. More than 33,000 people died there.’

What did you learn from the interviews?

‘Honestly, each interview was a lesson in life. I learned about the strength and vulnerability of the people in Theresienstadt. Most of the people I spoke to were still young when they ended up in the camp. Their parents knew what was happening, but the children had no real idea. By contrast, children who arrived there without parents were often fearful. Some witnesses emphasised what they learned from it and told me that without Theresienstadt, they would have evolved differently in their lives.’

Which interviews do you remember most vividly?

‘One special interview was with Anny Wafelman-Morpurgo, who spent a year and a half in Theresienstadt. She was given drawing and culture lessons in the camp by artist Hilda Zadikowa. For Anny, it was a kind of experience of inner beauty and freedom. That seemed special to me.’

‘One of the witnesses saw someone being beaten to death in front of his very eyes, over a bowl of soup’

‘But people also suffered hunger in Theresienstadt. Ronald Waterman, a child at the time, saw someone being beaten to death in front of his very eyes, over a bowl of soup. That made an indelible impression on him and defined his vision on life. One of the prime principles in his life is that people should be kind and friendly to each other. If everyone were to live by this principle, the world would be a very different place according to him.’

How do you get someone to talk about such personal events?

‘I phoned the witnesses beforehand to make an appointment and to explain what the idea was behind the interview. If the phone call felt right for both of us, the interview was scheduled. It’s important that you’re genuinely interested in your fellow human beings. If I noticed there was something that someone preferred not to tell, I didn’t persist.’

You’re a philosopher. What led you to research into the Holocaust?

‘After my PhD in 1993, on Meister Eckhart (a late medieval theologian and philosopher, ed.), I did a postdoctoral in Amsterdam into the Eckhart vision in the twentieth century. The question that intrigued me was: what is left of people’s vision on the world and religion after they have experienced a crisis? This lead me to Jewish writers, including Etty Hillesum who read Eckhart’s texts in Westerbork Camp (Etty Hillesum, a Dutch Jewish woman who survived Auschwitz and became famous after her death when her journals and letters were published in 1981, ed.). I gradually started reading other Jewish ego-documents which – after many detours – finally brought me to the witnesses of Theresienstadt.’

Is it not emotionally difficult, to work on the theme of the Holocaust?

‘My experience is that Jewish people who testify to their war experiences are often very resilient. Things become very clear for people in the deepest of crises. The texts that were then created, such as journals, are often very special. But it is also emotionally difficult. I know myself well enough to know that there are some things I can’t cope with. In the coming period, I’m going to focus on publishing the unpublished witness testimonies of Theresienstadt. To me, it’s meaningful work.’

You’re the initiator of Holocaust Memorial Day: you have interviewed a Holocaust survivor on the campus every year since 2009.

‘I thought it was a shame that little or nothing was organised around the Holocaust on our campus. That’s what gave me the idea of inviting a survivor every year. Not just anywhere on the campus, but in the Auditorium: the place where PhDs are defended, orations are held, and degrees are awarded. In preparation for the interview, I always say to the witness: ‘You are the river; I am only the riverbed. If it’s necessary, I will ask a question, but I follow you in your story’.’

How important is it for students to know what happened in the Holocaust?

‘You can learn a lot from people who have been through a lot. We still live in a world where there is much injustice, war even. You can learn a lot from situations in which something bad is happening. At the last edition, in January, Ronald Waterman got many questions from students afterwards, such as: ‘After so much hardship, how did you recover your strength and faith in humanity?’, ‘Which authors helped you with that?’, ‘How do you feel about anti-Semitism and xenophobia?’ and ‘Are you afraid there will be a new world war?’. Each year, the students listen very seriously to the witness and ask them serious questions. These witnesses matter. These are lessons in life from the school of loss.’

‘Each year, the students listen very seriously to the witness of the Holocaust’

‘The intention is to give Jewish witnesses of World War II a platform, for as long as it’s still possible. These are stories that are disappearing and which you will later not be able to hear anymore. They can only make us wiser.’

Stichting Stolpersteine Nijmegen

In addition to being a researcher at Radboud University, Ria van den Brandt is also chair of Stichting Stolpersteine Nijmegen. ‘Stolpersteine’, or ’tripping stones’, are small square stones with copper plates engraved with inscriptions that are placed in the paving stones in front of the last home of Jews murdered and persecuted in World War II and others persecuted. The initiative was started by German artist Gunter Demnig, who has already placed more than 75,000 Stolpersteine throughout all of Europe. The first Stolpersteine in Nijmegen will be placed in Stikke Hezelstraat, Lange Hezelstraat and Begijnenstraat on the 10th of April.