Policy officer Frans Janssen became translator after retirement: first novel has 1015 pages

-

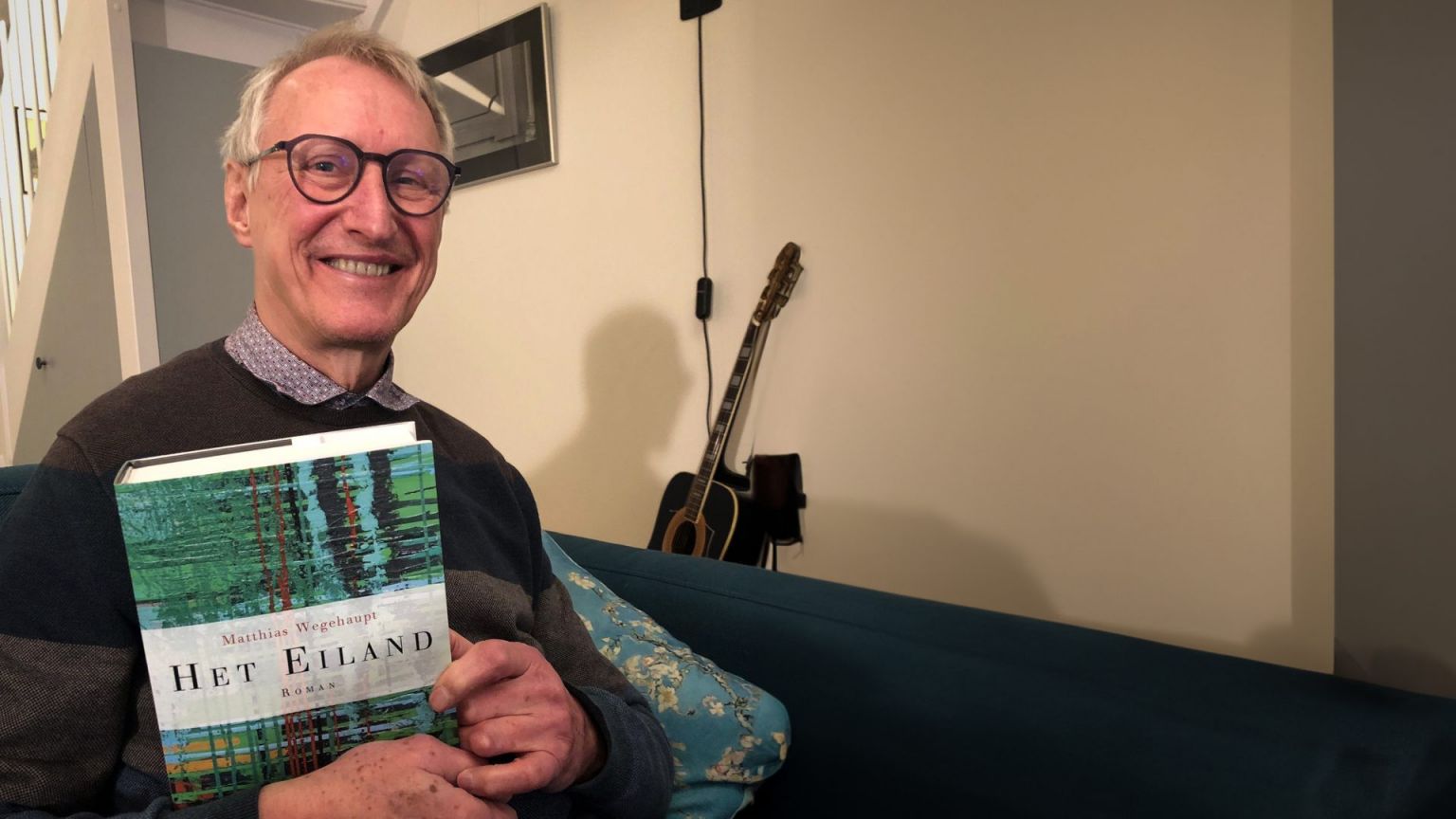

Frans Janssen with 'Het eiland'. Photo: private

Frans Janssen with 'Het eiland'. Photo: private

Matthias Wegehaupt’s novel on the DDR has an impressive 1015 pages. Former Radboud employee Frans Janssen decided after retirement to translate them all by himself. After all, he felt, the book deserves it. And because publishers were not lining up, he also decided to publish it himself. ‘I’ve had a wonderful time with this book.'

Not long after his retirement, Frans Janssen (68) stood in front of his bookcase and opened Matthias Wegehaupt’s 2005 novel Die Insel. ‘Such a shame’, I thought, ‘it was such a lovely book, and it never received a Dutch translation.’ That simple thought marked the start of a long journey. This next February 29th, Janssen will present Het Eiland, over a thousand pages translated by from German to Dutch by himself. And, because he could not find a publisher, Janssen has decided to publish the thick tome on the DDR by himself as well.

You’re a mathematician.

‘That is correct. I studied mathematics in Nijmegen. But I’ve always been interested in language. I even wrote a column with Vox’s predecessor, KU-Nieuws, titled Diary of an unemployed academic. Later, I began writing about math.’

After your studies, you worked at Radboud University for 35 years as a policy officer. Did you do any translating during that time?

‘No, not at all. After my retirement in 2020, I wondered what I should do with my time. My girlfriend still has a job; she leaves the house every day at 7:30. That is when I signed up with the translator’s trade school in Amsterdam, for translating German-Dutch. Every week, we had to translate a few fragments which would then be analysed down to the commas. It was very precise work; I loved it.’

Couldn’t you have started with a thinner book, rather than Die Insel’s 1015 pages?

‘I did! My first translation was a novella by Thomas Mann: De Paljas; forty pages. But I thought Die Insel was a truly great book, it deserved a translation. It’s about a painter who lives on a fictional island as a kind of hermit, as he describes life in the DDR. You might compare it with Het verdriet van België by Hugo Claus. Only it’s Het verdriet van de DDR…’

You even visited the writer, who is a painter like his protagonist, at his house. What was that like?

‘He’s 86 years old and lives on Usedom, which is an island in the Baltic Sea. My girlfriend and I were in the area, so I asked him if we could come by. He is a somewhat reserved man, but he was happy that someone went through the trouble of translating his novel for two years. We had already come into contact, as I had to ask him for permission to publish a Dutch version. I also e-mailed him regularly, whenever I didn’t fully understand his meaning over the course of translating.’

Two years, you said?

‘Yes. I translated roughly twenty pages per week, then I would have my girlfriend read the text, and I would process her feedback. That’s how I came to roughly 20 to 25 pages every two weeks. I worked at it every day; I usually started in the morning, after doing the puzzles in the newspaper, and I worked until the end of the afternoon. I’m also the stay at home spouce, so then I would have to go and take care of dinner.’

What is your connection to the German language?

My mother is German. My Dutch father wound up in Germany during World War II. As children, we always assumed he was there due to the Arbeidseinsatz or something similar. We never spoke about it at home, and he died in 1981. It wasn’t until later that we found out he was aligned with the Germans. At the end of the war, my mother wound up in the Netherlands with her son, my elder brother Wolfgang; my father was imprisoned for two years. She was all by herself and from that moment on only spoke Dutch – speaking German at that time was not a smart move.’

‘For me, German literature is a roundabout way to come to grips with my roots’

‘Later, we would holiday in the Black Forest. My mother’s family lived in East Germany, on the other side of the Iron Curtain, so I’ve always spoken a lot of German. I can read German novels as easily as Dutch ones. For me, German literature is a roundabout way to come to grips with my roots.’

Did your translating work make you see the language in a different light?

‘Wegehaupt wrote a lot of dialogs, and through that you can clearly see that Germans simply talk differently that Dutch people. They use first names a lot less; if you want to make such a conversation sound natural in Dutch, you have to make it a bit more folksy.’

Did you try to find a publisher for Het Eiland?

‘Yes, I lugged the book around, but not a single publisher was up to the task. Because I loved the book so much, I decided to do it myself. I love hardcovers and ribbon markers, so I made a lovely edition with a painting by Wegehaupt on the cover.’

That must have been a big investment.

‘It was; even if I sell every single copy, I will not break even. But it’s worth it. For two years, I had a wonderful time with this book, and now it’s available for everyone to read. Other hobbies would have also cost time and money.’

Het Eiland will be presented at book shop Roelants in Nijmegen, on Thursday, February 29th, 17:00 o’ clock. You can sign up via roelants.nl

Translated by Jasper Pesch