Political study in one of the most dangerous cities in the world

-

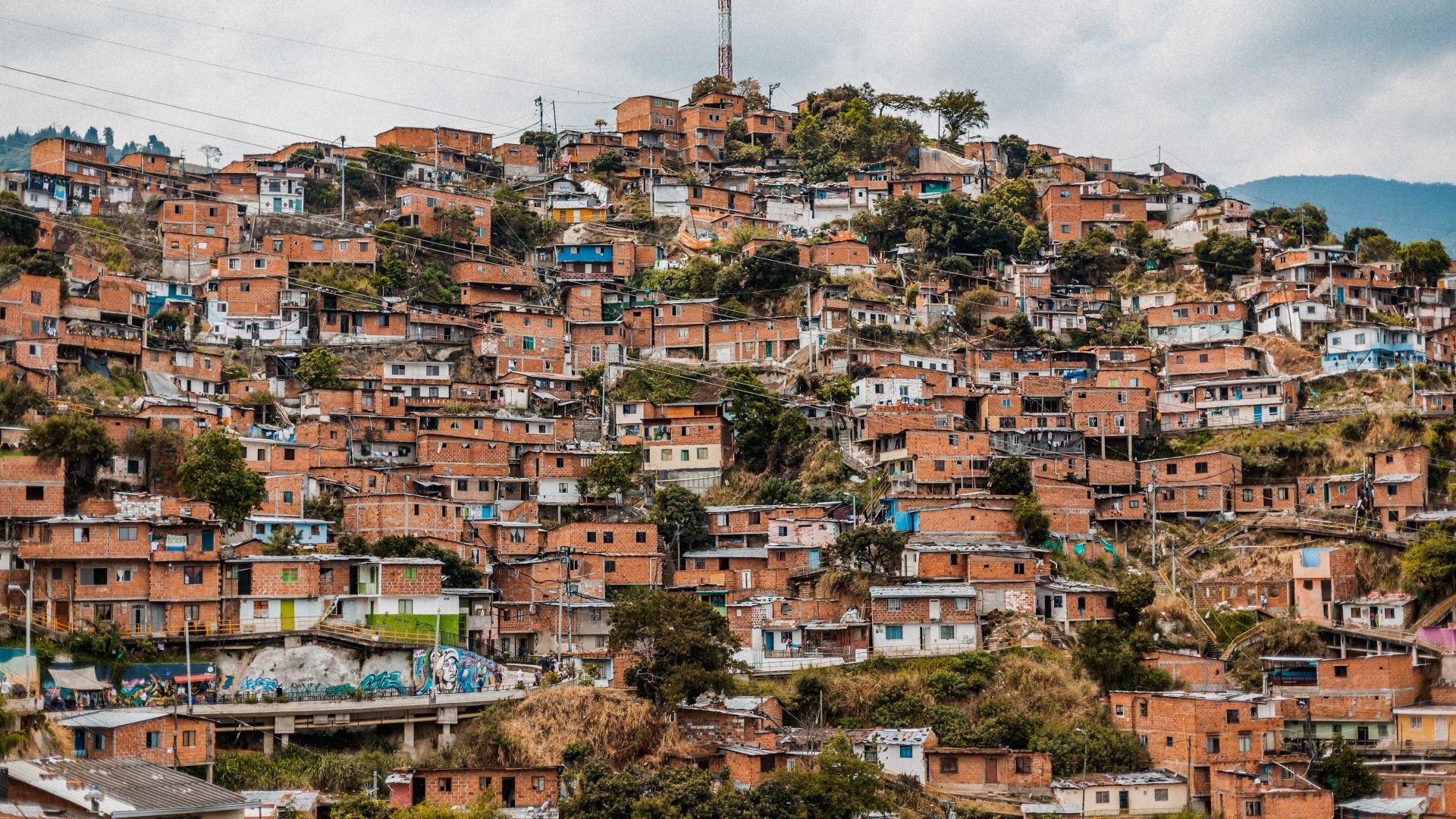

Medellin. Foto: Brian Kyed via unsplash

Medellin. Foto: Brian Kyed via unsplash

Researcher Martijn Koster is about to embark on a thrilling research project. For one year, the anthropologist and his team will be researching the relation between marginalised citizens and the state in the favelas of Recife (Brazil), Medellín (Colombia), and Santiago de Cuba (Cuba).

In 2022, there were 1494 homicides in Recife. That staggering number puts the Brazilian city in the top 40 of the world’s most dangerous cities; the list is updated every year by the Mexican organisation CCPSJC. The Colombian city of Medellín, the hometown of drug kingpin Pablo Escobar, is safer now than it ever was before, but there are still some spaces you should wander around at night. ‘This means that you should be careful and avoid travelling alone through the city at night’, according to Koster, researcher and Associate Professor of Cultural Anthropology and Development Studies at Radboud University.

Additionally, most of the murders in Recife are drug-related, as explained by Koster. Firefights are usually between the police and the gangs, or the gangs amongst themselves. There is very little real risk, provided they don’t get involved, avoid drugs, and clearly show that that is not the subject of the study. ‘Of course, neighbours do worry about stray bullets, which is much less common in Rotterdam or Amsterdam.’ That is why safety issues are a main part of the research preparations. ‘The safety of the researchers and the participants is paramount. I hope to recruit people whose thesis or other works have prepared them for these circumstances.’

Wingless pigeon

The study will focus on housing, governance, elections, and activism. To fully grasp these themes, it is important for the team of postdocs and PhD candidates to stay in the neighbourhoods. ‘People appreciate it if you live close by. That makes easier to make connections and gain trust, which improves the quality of your data.’

‘They have a space inside where they relieve themselves on cardboard or paper’

Koster is very familiar with the cities and neighbourhoods his team will be staying in from January onwards. In Santiago de Cuba, he visited Fidel Castro, the ‘most famous local’; the former president’s urn is in a local cemetery. But Koster has been to Recife the most, starting back in 2003. The neighbourhoods he will investigate are lined with 3-story stone houses, with plumbing and electricity. But there are also wooden houses on stilts in the river and the mangroves, where people tap electricity and water. There is no plumbing; people have a space inside where they relieve themselves on cardboard or paper, before chucking it in the water outside, Koster says. ‘They call that a wingless pigeon.’

Combating poverty

It’s hard to imagine a bigger contrast than that between Recife and Wageningen, where Koster lives with his family. On average, Koster leaves his duplex once every two years for research in Latin America; he’s visited ten times since 2003. ‘Taken together, I’ve done field work in Brazil for two years. Additionally, I’ve also spent several weeks in other Latin American countries.’

Koster was a student of Development Studies in Wageningen. ‘Back then, I had the naïve idea that methods would be found that would solve world poverty; I wanted to be a part of that. But at some point, I realised that solving it was going to be extraordinarily difficult; contributing to reducing inequality is much more realistic.’

Koster finds it interesting that measures (he refers to them as ‘interventions’) are always aimed at improving the lives of groups of people, but they rarely do in practice. ‘More often than not, they even contribute to inequality.’ According to the researcher, those interventions are often form over substance. ‘It’s giving people a vote on what colour to paint the doorframe, but not on the renovation as a whole.’

Cardboard survival

The houses in the low-income areas of Recife are often built by migrants; they are often from the inner countries, having left the arid, savannah-like areas in search of a better life in the city. Consequently, many residents lack proof of ownership of their house; they’re in big trouble if there are suddenly plans for a road right through their neighbourhood. ‘That makes them vulnerable, as they are legally not allowed to stay.’

Most residents make a living through the ‘informal economy’: collecting bottles, metal, and cardboard for payment; running fruit- and vegetable stalls along the roads; cleaning houses in the richer neighbourhoods; and selling candy near traffic lights. But despite the low incomes, the researchers need not fear petty theft. ‘Just so lang as you don’t show off your laptop or camera in the street’, Koster says. ‘Generally speaking, safety increases as you spend more time doing research. Once you’re familiar with the head of the residents’ association or other active locals, thieves know better than to steal your phone.’

Research

Koster’s research is financed through a Consolidator Grant from the European Research Council. The grant provides two million euros over the course of five years, which is used to pay Koster’s salary, as well as those of three PhD candidates (for four years), and two postdocs (for 2.5 years). Koster and his project will move to Wageningen University as of January 1st. ‘They have a research programme whose theme lines up perfectly with mine: politics of development. They’re looking into the politics surrounding development interventions.’

The prospective PhD candidates and postdocs still need to be interviewed. The current plan is for Koster to travel down to Latin America a couple of times, for a few weeks at a time; the PhD candidates will be doing two six-month field studies, and the postdocs will be down there for a couple of months. It is imperative that they speak the language, according to Koster.

Money for votes

Political schemes don’t often line up with the needs of vulnerable residents, Koster explains. They are often pushed from their homes without (adequate) compensation, or they’re assigned living spaces in the outer rims of the cities. ‘That makes the travel times to the city centre insurmountable for street vendors.’

The neighbourhoods often trade votes for political favours; sometimes politicians (literally) buy votes under the table. They also tend to hand out free food or promise that illegally built houses are allowed to remain.

By investigating these issues, Koster hopes to better understand the relationship between residents and the state, seen from the perspective of marginalised citizens. ‘What is their experience; what does that relationship entail? How do they shape it? And how do they imagine the state?’

Trust is a key component. There is a Brazilian word: enrolação, which roughly means ‘to pack with nice words.’ ‘On the one hand, people get excited by big political speeches, but on the other, there’s enrolação. That deep-rooted distrust mixed with enthusiasm, the tension between hope and suspicion, are the stepping stones for rethinking how we conceptualise politics in the periphery. The goal of our research is the development of new theories in this area, from a residents’ perspective.’

Through the proliferation of knowledge, Koster hopes to contribute to less exclusion and better housing. His participants will not profit from it right away, though. ‘There’s always the hope that politicians immediately pick up the slack, but reality is more complicated than that. However, I am familiar with several planners in Recife who know how disastrous a move to the fringes would be for residents, based on earlier research. Although they take a long time, I do see changes for the better.’

Translated by Jasper Pesch