Radboud researcher advocates for more recognition for indigenous soldiers from World War II

-

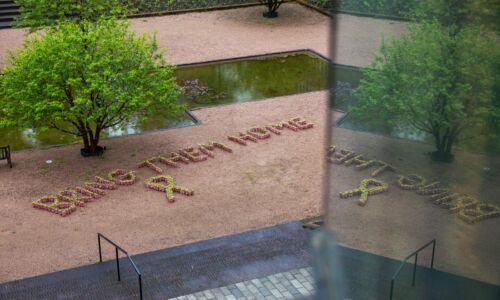

A cleansing ritual preceding the commemoration. Photo: Johannes Fiebig

A cleansing ritual preceding the commemoration. Photo: Johannes Fiebig

During a special commemoration at the Canadian military cemetery in Groesbeek, the role of Indigenous Canadian soldiers in the liberation of the Netherlands during World War II was acknowledged today. Nijmegen Americanist Mathilde Roza is conducting research on this group.

To date, approximately 120 Indigenous Canadian soldiers are known to be buried in the Netherlands, with over sixty in Groesbeek. This group is often overlooked or faces stereotyping, notes Americanist and associate professor Mathilde Roza.

She previously created the exhibition Albert & Theo at the Vrijheidsmuseum in Groesbeek, which was about the friendship between an American Mohawk soldier, Albert Tarbell, and Nijmegen resident Theo Smolders. She is now working on a major overview exhibition set to open in May 2025, focusing on the role of Indigenous soldiers in the Dutch liberation. She is also involved in the recent memorial service that was organised in collaboration with the Royal Canadian Legion and the Dutch Foundation for North American Indians (NANAI).

When it comes to the Indigenous population of Canada, which groups are included?

Mathilde Roza: ‘Canada is home to three major Indigenous groups: the Inuit who live around the Arctic Circle, and two others. First, there are the groups known as First Nations, and then there are the Métis, who have a mixed heritage of French settlers and Indigenous peoples. Overall, there are over six hundred distinct Indigenous communities that fall into these three categories.’

How have these groups been treated in the past?

‘That treatment has taken various forms. Initially, there were diplomatic and trade relations with many Indigenous peoples. However, as more settlers arrived, violence increased. Indigenous communities were confined to reservations, and there were aggressive efforts to assimilate them, notably through the 139 residential schools established from the 19th century onward. In recent decades, more and more groups have gained recognition for their sovereign status.’

How did these groups end up in the Canadian military?

‘Even before conscription was introduced, large numbers of young Indigenous men and about eight hundred women volunteered for the military, and that level of voluntary participation remained high. There were several reasons for this. Economically, many faced limited opportunities since they couldn’t leave the reservations, where options for well-paying jobs were scarce. Most worked as farmhands, hunters, or guides. The military offered them greater opportunities, including financial ones.’

‘For the Canadian government, it was a success story of an assimilated group, but that conflicted with the experiences of the Indigenous group.’

‘Additionally, the warrior had a special cultural position in their community. The fathers and grandfathers of those volunteers had sometimes fought in World War I or other wars, and they were held in high regard. This role enhanced their sense of being able to shape their cultural identity.’

What was their position within the military?

‘They had very limited opportunities for promotion. The highest rank most achieved was corporal, with just a rare exception or two reaching higher. Still, within the military, they might have been better accepted than outside of it. In a way, the stereotype of them as exceptional and brave fighters worked in their favour; some non-Indigenous soldiers looked up to them. However, this perception also had a dark side: many served as scouts or sharpshooters and faced high risks.’

And what was their status after the war?

‘For the Canadian government, it was a success story of an assimilated group. They believed they didn’t need to do anything further. This perspective clashed with the experiences of the Indigenous community. It’s possible that the veterans laid the groundwork for organised activism. The exact connection between the war and the struggle for civil rights and sovereignty still needs more exploration.’

Why hold this commemoration now?

‘It’s a tribute to a group of soldiers who are not often remembered. This commemoration highlights the importance of acknowledging them as well. We’re working on various initiatives with Veteran Affairs Canada, including the upcoming exhibition at the Vrijheidsmuseum and commemorative events next year.’

‘By shining a light on this group, we make it clear that they are also relevant to the Netherlands. Our country was liberated by them, and there are stories of children born to Indigenous soldiers, as well as Dutch women who married Indigenous men and moved to reservations in Canada. There are many more such stories. This commemoration serves as a reminder to keep recognising their contributions.’

Translated by Siri Joustra