Scientists use the most water

-

During the summer of 2017, the university distributed inflatable pools on campus. Photo: Annemarie Haverkamp

During the summer of 2017, the university distributed inflatable pools on campus. Photo: Annemarie Haverkamp

Every day at Radboud University a multitude of toilets are flushed, water bottles filled, laboratory equipment cooled and plates washed. What is the total volume of the drinking water we use, and how can we reduce our consumption?

In 2019, a total of 101,307 m3 of drinking water flowed from the campus taps. This comes down to 3.6 m3 or 3600 litres per student or employee, calculated Toon Buiting from the Department of Property Management. According to the National Institute for Family Finance Information (NIBUD), a one-person household uses thirteen times this amount on a yearly basis: 46 m3. Incidentally, Radboud university medical center is not included in this calculation: in 2019, they used another 231,000 m3 of drinking water.

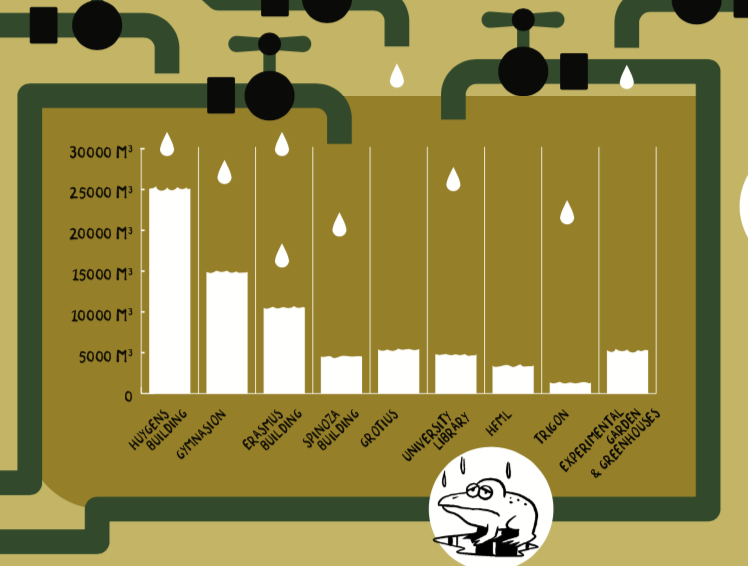

Buiting also calculated for VOX how much water was used last year by each individual university building. The Huygens building is a big consumer, partially because laboratories require a lot of water for things like cooling. The labs are responsible for approximately one third of the total water consumption on Campus. This explains why sometimes smaller buildings still have a relatively high consumption. Buiting: ‘Take the Nanolab. It’s very small, but uses 1230 m3, a proportionately large amount.’

’12 percent of the water is used for catering’

And besides the labs? Approximately 12 percent of the water is used for catering: in the dishwashing area or behind the bar. And with 8 percent of the water we take a shower after sporting activities. The rest goes to daily activities like flushing toilets, washing hands, filling water bottles and cleaning. Even though according to Buiting, cleaning requires less and less water – a microfibre cloth sometimes works wonders.

Because of all the water used for catering and showers, the Gymnasion is the second biggest consumer of water, followed by the Erasmus building. Even though in the case of the Erasmus building, some of this water was needed for the construction work in the Thomas van Aquinostraat. A lot of water was used in the demolition phase to avoid stirring up too much dust, and in the construction work to mix building materials.

Coolers

Over the past years, substantial steps have been taken to reduce water consumption. In 2012, water usage amounted to 172,423 m3, corresponding to 7.2 m3 per student or employee. Buiting: ‘Our goal is to reduce water consumption by 2% per year, on average in recent years we have achieved a reduction of 6%.’

To a large extent, this reduction is due to water-saving measures in laboratories. ‘Eight years ago, water consumption in the Huygens building was twice as high as it is now.’ In the past, laboratories generally used spiral coolers: water flows through the spiral, heats up during cooling, and is flushed into the drain. Many of the newer systems work with air and there are even cooling systems that don’t require any water, even though these sometimes use proportionately more energy.

Another place where the university saves water is on the roof of the Erasmus building. Until recently, the roof was the location of a ‘wet cooling tower’ for air-conditioning. This sometimes caused problems, which led to extra water being used. The tower has now been replaced with a ‘dry cooling tower’ that doesn’t use any water. The new cooling systems for server back-ups also don’t use any water, and air humidifiers are only used in the labs. Buiting: ‘Air humidity in offices is usually high enough. Employees sometimes complain about dry air, but this is usually due to dust.’ Tidying up and cleaning are more effective than switching on an air humidifier.

Rain water

All the drinking water on Campus comes from Heumensoord. In addition, on the roofs of the Grotius and Huygens building there are grey water systems: large containers that catch rainwater which is used to flush the toilets in those buildings. Ten years ago, when the containers were installed, the idea was that this would be a more sustainable system. After all, it eliminated the need to pump and filter drinking water for ‘lessor purposes’ such as flushing away poo. But in practice, the sustainability advantages are limited, explains Buiting. ‘Our drinking water comes from sandy soil, so it doesn’t have to be filtered as much as, say, surface water. But we did have to install additional concrete containers and pipes.’ The reduction in drinking water consumption doesn’t compensate for the costs and use of materials.

What’s more, the grey water system increases the risk of legionella. Since drinking water and rain water run through different systems, drinking water flows through the pipes slowly, in some water points that are used less frequently almost too slowly. In view of all this, during the construction of the new Maria Montessori building, the grey water system wasn’t even mentioned as an option.

What Radboud University does invest in heavily, in an attempt to reduce gas consumption, is the geothermal heating system. In winter, the university pumps groundwater at approximately 10° Celsius from a storage area behind Mercator 2, a heat pump then heats the water and uses it to heat the Campus buildings. As the water cools off, it’s redirected to another underground storage source near the botanical greenhouses. In summer, water from this source is used to cool the buildings. Approximately 1 million m3 are therefore pumped back and forth. In well-insulated new buildings like the Huygens building, the geothermal heat pump seems to work very well, says Buiting. ‘We’re now trying it in the old buildings. Although we’ll probably always need a bit of gas for these buildings, for instance when it freezes hard.’ If you would like to know more about the geothermal heat pump, Radboud University has made a short film about it.

Miglė schreef op 20 februari 2020 om 16:25

The link for the short film does not work :/