Should we vaccinate young children or not? Even the paediatrician is still on the fence

-

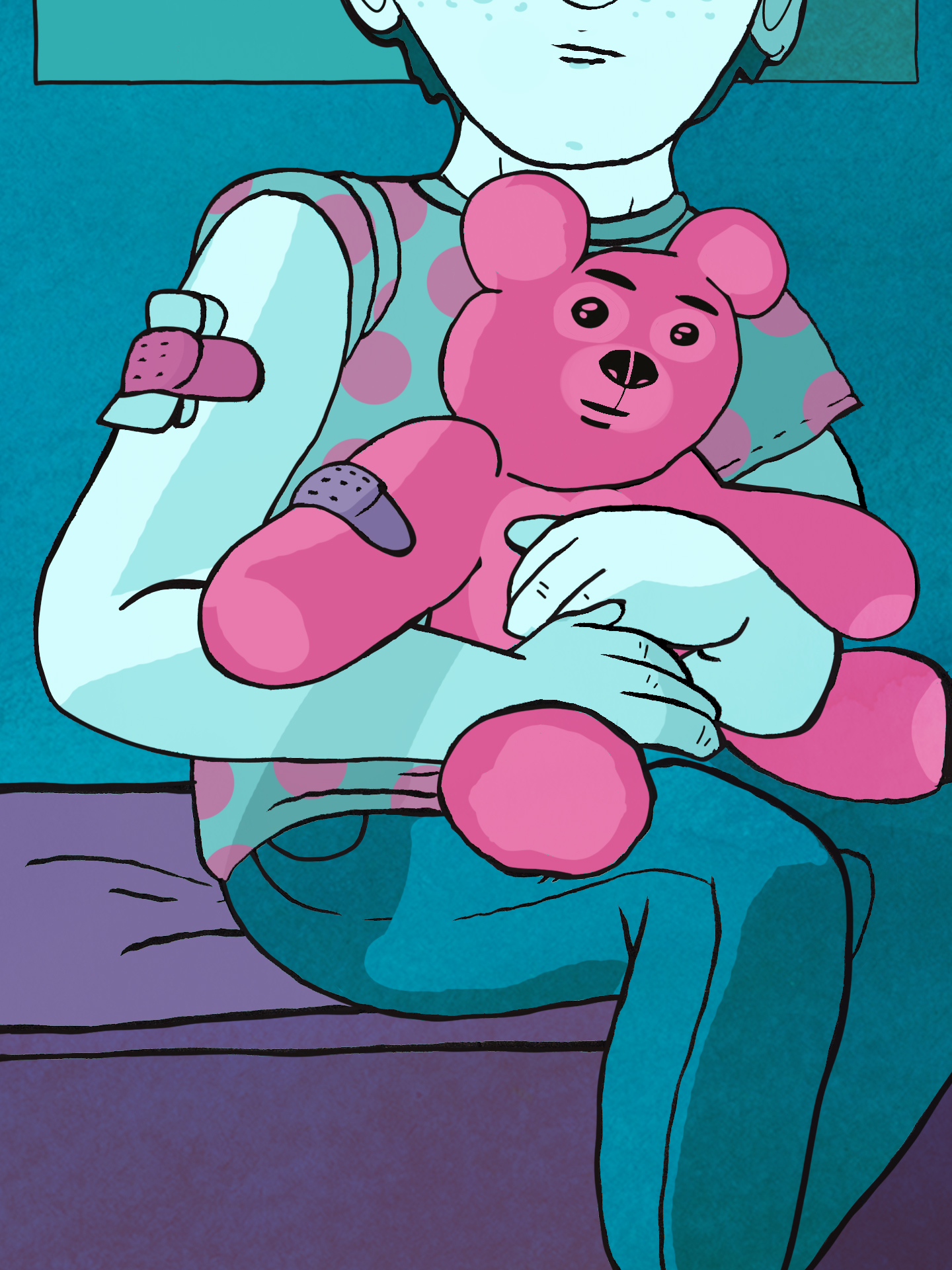

Illustratie: Ivana Smudja

Illustratie: Ivana Smudja

According to Professor of Civil Law André Nuytinck parents are violating their legal obligation by having their young children vaccinated. A Radboud university medical center paediatrician and an ethicist have a more nuanced perspective on the matter. ‘What exactly am I doing to my children by having them vaccinated?’

With the booster campaign for adults in full swing, December saw the start of a new vaccination campaign, aimed at young children (aged 5 to 11) and starting with young patients with underlying conditions such as asthma or congenital heart defects.

Starting from mid-January, children in this age group without heightened medical risk will receive a vaccine invitation. This was decided following a positive recommendation from the Health Council of the Netherlands, which the Dutch government subsequently followed. According to the government advisory body, the advantages of vaccination outweigh the disadvantages even for this age group. The same conclusion had previously been reached for teenagers.

Parents are now facing a choice – possibly in dialogue with their child – of whether or not to plan in a jab. It’s up to them to weigh the risks of a COVID-19 infection against the potential side effects of the vaccine.

Low risks

This is no easy choice, as Radboud university medical center paediatrician Mathijs Binkhorst is the first to admit because of how nuanced and therefore complex this weighing of pros and cons is. ‘With young children, we’re talking about weighing the very small risks of a COVID-19 infection against the very small risks of a vaccine.’ He therefore emphasises that this is an invitation to vaccinate, certainly not an imperative. ‘It’s certainly not the direction we should be taking.’

To begin with: what are the risks of a COVID-19 infection? Although very few young children become seriously ill from COVID-19, the risks are not non-existent. A child that is unlucky may end up in bed with a fever for a few days. So be it, they’ll get over it, you might say.

‘I personally tend towards waiting a little longer, until we know more about it.’

But this is not the only risk. So far, over 300 children have been hospitalised with COVID-19. Some of these hospitalisations, around 100 to be precise, concerned children with a severe inflammatory response (MIS-C) as a result of COVID-19. In many cases, these children ended up at the ICU. Binkhorst: ‘The immune system turns against the body and attacks multiple organs. It’s a very serious condition. Luckily, no children have died of it so far.’

‘This is the worst thing that can happen to a child following a COVID-19 infection,’ says Binkhorst. This risk is comparable with the worst side-effect of the vaccine for children: an inflammation of the cardiac muscle (myocarditis) and/or the pericardium (pericarditis). This has also so far not proven fatal to any child. ‘What we see in the vast majority of teenagers is that they largely recover within a few days.’ According to the paediatrician, this side-effect has so far occurred in twelve teenagers – mostly boys – following a COVID-19 vaccination. So even less than the number of young patients diagnosed with MIS-C.

If you want to make an informed choice, you should also consider other consequences of a potential infection, says Binkhorst, such as the risk of contracting Long COVID following an infection, which is probably 2% to 5%. On the other hand, there is also a group (albeit a much smaller one) that suffers an allergic reaction after being administered the vaccine.

Taking all of this into account, Binkhorst finds the advice of the Health Council to offer adolescents and young children with a heightened risk a vaccine ‘justifiable’. Concerning the vaccination programme for healthy young children, he is more sceptical.

Binkhorst will therefore not be the first in line in January to plan an appointment for his six-year-old daughter. ‘Obviously, this is a decision I want to take together with my wife and my daughter. I personally tend towards waiting it out, until we know more about how the vaccine affects this specific age group.’

For instance, the rise of the Omicron variant brings further uncertainty. ‘Our priority should now be on administering boosters to adults. This is what will have the greatest impact on public health. We can always see later whether we want to vaccinate young, healthy children.’

Long-term effects

A far less nuanced voice than that of paediatrician Binkhorst comes from a surprising source. Via social media, Professor of Civil Law André Nuytinck, who specialises in family law, distances himself from the vaccination of young children using powerful language.

On 11 December he wrote on LinkedIn: ‘I’m fully aware of the fact that I’m repeating myself, but this concerns our young or even very young children, aged 5 to 11. Dear parents, don’t vaccinate your young children – as long as they are not currently experiencing any health problems – against COVID-19, because this virus will hardly, if at all, make them ill.’

Professor Nuytinck, who does not wish to further expand on his self-proclaimed cry for help in an interview, refers to Article 247 of the Civil Code in his message, which states that parents are responsible for the mental and physical well-being and safety of their child. ‘Please don’t violate your legal obligation. Vaccination is not in the interest of these young or very young children.’ Nuytinck urges parents who are in doubt to wait with vaccinating their children until the long-term side-effects are known.

The long-term effects of the COVID-19 vaccine are indeed not yet known, confirms paediatrician Binkhorst. We simply need to keep collecting data in the coming years. ‘But so far, six months into the vaccination campaign, no serious side-effects have yet come to light. It’s very implausible that such side-effects would emerge at a later stage.’

What’s more: ‘We also don’t know what the long-term effects of a COVID-19 infection are.’ It is equally possible, says Binkhorst, that some children who suffer a severe inflammation response (MIS-C) follow a COVID-19 infection will still experience the effects years later.

‘The COVID-19 debate is turning into a battle between scientists who are being pushed into different camps’

And yet, Binkhorst is particularly careful to not contribute to further polarisation. ‘What we see now is that the COVID-19 debate is turning into a battle between scientists who are being pushed into different camps. I prefer to walk the middle road.’ For example, Binkhorst understands the need to vaccinate adults and teenagers. ‘But that doesn’t mean that I support all aspects of government policy. I’m not a proponent of 2G (whereby people only get access to services if they are vaccinated or recovered, Eds.). And I also believe that schools should only be closed as an absolute last resort.’

Jelle van Gurp, Assistant Professor in Clinical Ethics at Radboud university medical center, more emphatically distances himself from Nuytinck’s plea. ‘He uses these really big concepts, but they are colourless. Nuytinck appeals to people’s gut feeling. But if I was considering vaccinating my child, I’d like to ask him to tell me more precisely: What is it exactly that I’m doing to my child?’

The long-term effects, yes, those are a risk factor. But on the other hand, says Van Gurp, there is also the risk of young unvaccinated children falling seriously ill. ‘As a parent, you may think your child won’t be the one to get MIS-C. But this is remarkably naive, because the truth is that you simply don’t know, which means it’s a risk you must weigh in.’

School closures

According to ethicist Van Gurp, the generally accepted idea is that children should first and foremost personally benefit from a vaccine, as with any other medical procedure or study. The interests of society, such as raising the vaccination rate or preventing lockdowns and school closures, should always come second. And the Health Council claims that this is indeed the rationale behind their recommendation for a vaccination programme for young children.

But this is not to say that those indirect advantages of vaccinating children, which ultimately benefit both the children themselves and society as a whole, should be shoved under the carpet, says Van Gurp.

‘Preventing lockdown may well lead to the greatest health gains’

Indeed: ‘I actually think that these arguments weigh as much as the medical considerations. Through my collaboration with Karakter (Centre for Child and Youth Psychiatry, Eds.), I can see how serious the problems are that many children and young people face in the pandemic, and especially during lockdowns. If we can prevent these problems with vaccines, this may ultimately be the way to book the greatest health gains. So many children are lost, in unhealthy home situations, and in need of help. The pandemic has really exposed all these vulnerabilities.’

Solidarity

Van Gurp also raises the issue of whether children also have a responsibility towards society. ‘Since the start of the pandemic, there has been a lot of discussion about solidarity. Don’t children also play a role in this?’ The ethicist doesn’t have any ready-made answers. ‘What it boils down to is that we’re asking children to expose themselves to a very limited risk linked to the vaccine for the benefit of a larger group of older people who haven’t yet taken all the necessary precautions to protect themselves.’

But, he emphasises, the adults who are not vaccinated do not form a homogenous group. Not all of them are opponents of the vaccination policy. ‘Some people couldn’t get vaccinated, were unfortunate in the fact that the vaccine didn’t work for them or were simply unable to properly process the government’s information.’

We should therefore not expect any wise council from ethicist Van Gurp. ‘If I take the time to think about it, I expect that I will ultimately have my children vaccinated. But I’m not sure yet. I need some kind of future perspective: Will we be vaccinating people forever? And must children be part of this?’

What Van Gurp does know is that he disagrees with Professor André Nuytinck’s plea. ‘His language is too rhetorical – which is something a lot of people are sensitive to. They think that if someone with so much stature takes this kind of position, he must be right. Whereas in fact, his claims are not supported with thorough medical knowledge of vaccines. You’d expect someone who took his position as a professor seriously to produce a more nuanced, less rhetorical, and better substantiated story.’