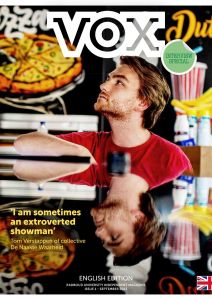

Showman Tom Verstappen never wants to leave Nijmegen

-

Photo: Duncan de Fey

Photo: Duncan de Fey

Tom Verstappen (26) calls himself a Catholic atheist. The former Arts and Culture Studies student is hooked on Nijmegen, can express his creativity with the activist art collective De Naakte Waarheid, and makes music with his band, Misprint. He is currently working on a podcast about the ‘tambourine lady’.

When Tom Verstappen missed the deadline for his Bachelor’s thesis in Arts and Culture Studies and decided to start his thesis all over again, he and a friend organised a house party on three floors of student complex Hoogeveldt. The theme: Dante’s Divine Comedy. ‘We had set up the bottom floor as the Inferno, for dancing and kissing. The middle floor was all about Reflection; you could go there to drink tea. The top floor was Heaven, a space to chill out by the pool. Two hundred people attended. I almost lost my lease because of that party.’

Broodje Spee

The grand-scale house party says a lot about Verstappen’s creativity and his drive to connect. Verstappen has since graduated and works as a programme maker for literary organisation Wintertuin, where he links literature to other art disciplines. He is also part of the collective De Naakte Waarheid (The Naked Truth) and the band Misprint, and he works to strengthen the local music scene with various initiatives at incubator De Basis.

Born and raised in Nijmegen, he has a soft spot for the local peculiarities of his home city, which is why he chose to meet us at Cafetaria Keizer Karelplein. ‘Look, they sell Broodje Spee here! I love that. It’s a local snack, invented in the 1990s by Pieter Spee, a student. It consists of a soft, white bun with a cheese soufflé, chilli sauce, peanut sauce, and onions. They have it on the menu in lots of places. You can compare it to Groningen’s “eierbal”.’

On the terrace of the chip shop, watching the many cyclists and passersbys, Verstappen mentions that he spent two months this year without a bank card. After cutting his ING bank card in half on stage in front of a sold-out Merleyn, he wanted to switch to ASN, but ING was being difficult. ‘I wanted to go on holiday, so I ended up having to open another ING account for a while; there was no other way.’

Benefit

This interview is part of Vox’s interview special, which can be found in the Vox stands on campus, starting next week. The magazine contains interviews with student and NEC player Dirk Proper; researcher Samira Azabar; virologist Marc van Ranst; producer Tom Verstappen; doctor Tanya Bisseling and her student daughter Jasmijn Olde; friar Stefan Ansinger; and influencer Manon van den Bos.

Cutting his bank card in half was part of the ‘Benefit Night for Yourself’, an anti-capitalist celebration by De Naakte Waarheid, with music, performances, and an auction. The idea was that the entrance fee and other proceeds would be shared among the visitors who stayed until the end. In the end, you could also choose to donate the money to a charity, which was what most people did.

The benefit night was one of the many extravagant projects of De Naakte Waarheid. The collective originated at the Nijmegen secondary school SSgN. In Cultural and Arts Education, Verstappen was asked to produce a social criticism paper. Together with two friends, he created a complicated rock opera on how Tinder is not about real love. ‘We performed it with a whole group, all mediocre musicians. In the end, three of us remained: Jens Bouwman, Willem Baltussen, and I.’

During their studies, the collective took part in a number of music competitions, including De Roos van Nijmegen. ‘We pretended to be a rock band, even though we weren’t. We did give it a serious shot, though, with a lot of audience participation. The audience voted us through to the final, where we wore Jesus outfits and took a huge butterfly on stage. We’d done our very best, and came second.’ Verstappen laughs. ‘Some people were really angry that we’d made it so far, because we cared more about the show than the music.’

De Naakte Waarheid appeared at many festivals, but in the end it was too much. ‘Our artistic principle is that every show should be different, with different dance moves and outfits. That means a lot of work, and before you know it, you’re rehearsing three times a week. So we decided to slow down a bit.’

Geert Wilders

Social engagement is the collective’s main drive. Verstappen himself became socially involved as early as in primary school. ‘I grew up at the time when Geert Wilders entered the House of Representatives with the PVV party. That kept me busy. I was in a so-called black school. At my football club, there were lots of boys from other schools, and they found children from other backgrounds very scary. I resisted that. It made me aware of how new Dutch people are often seen.’

In secondary school, he made friends who were also very politically aware and denounced the growing right-wing sentiment in the Netherlands. With De Naakte Waarheid, they gave shape to their activism. ‘It starts with believing that we can change something. If we then get a stage, we must use it for that purpose. We feel responsible.’

‘I grew up at the time when Geert Wilders entered the House of Representatives with the PVV party. That kept me busy’

Since the pandemic, the collective has expanded their repertoire beyond performances alone. For example, they organised a counter-reaction to the Vizier op Links stickers. ‘It was in the news a couple of years ago: radical right-wing stickers being placed on the front doors of left-wing politicians saying “observed location”. We recreated the same stickers, but changed the text to: “adored location”. It was a playful statement against harassment.’

During the Four Days Marches, they held a dance night at Merleyn, entitled Greetings from Zingelong. ‘We created a poputopia, because we want to make the world a more beautiful place. We prefaced the songs we played with social criticism on Instagram beforehand. For instance, we posted an excerpt from Kelis’ ‘Milkshake’ with the story that Kelis uses oat milk instead of cow’s milk for her milkshake.’ Greetings from Zingelong is due to return to Merleyn on a regular basis.

Verstappen takes a sip of his iced tea. He’s a stage animal, he confesses. ‘I can be a bit of an extrovert showman. It was the same when I was president of KNUS, the study association of Arts and Culture Studies. I like being the centre of attention. The stage really stirs something in me. It makes me want to stand out, and then I really go for it.’

This is also apparent in his other project, the band Misprint. As a singer and keyboardist, he moves around a lot during performances, and uses the entire stage. ‘When I get the audience to do what I want, it makes me feel powerful, but in a good way. I enjoy the interaction.’

The band could not be more different from the collective – it’s made up of three former Arts and Culture students and a bass player whom they met via through their extended network. ‘I can express something different about myself in both projects. De Naakte Waarheid is conceptual, while Misprint is more personal.’

They started out as an English-speaking punk band, but soon found out that that didn’t work very well. ‘One time, at the Cultuurcafé, we saw a band playing badly and we thought: we can do better than that. But I found it hard to write in English, and we weren’t very good at punk either. We’re just not angry enough. So we turned into a Dutch-language indie rock band.’

Pierson Riots

These days, Misprint is doing very well. Late last year, the band scored a hit with ‘Lege koelkast’ (‘Empty fridge’). ‘You can sing along to it, and people have shared it everywhere. It became a local hit. It was great fun to experience! Still, if I’m honest, I’m personally more taken with our new single ‘En, soms’ (‘And, sometimes’). That song made people cry. That’s more important to me.’

This summer, the musicians performed as the opening act at the Valkhof Festival. For Verstappen, it was a dream come true. This Nijmegen festival introduced him to a lot of music. In September, Misprint will play at Misty Fields, a festival that features bands the Misprinters themselves have been listening to for a long time.

‘I love cult heroes and “village idiots”’

Verstappen wants to show us something. He waves the cafeteria manager good-bye, and walks around the premises towards the Quack monument. He pauses on the grassy area between the two lanes of Nassausingel. ‘Have you ever noticed these sculptures before? They’re a bit hidden.’ He doesn’t particularly like them, but they intrigue him. He chuckles. ‘The municipality of Nijmegen received them as a gift to make the city more attractive, but who sees these statues now? The Quack monument is also a gift, and the municipality didn’t actually want it at all.’

The Nijmegen culture won’t let go of him. For the past two years he’s had an NEC season ticket, one of Misprint’s lyrics features party artist Ronnie Ruysdael, and in a show by De Naakte Waarheid, he used a slogan from the Pierson Riots: ‘Lansink’s an idiot’ (in reference to CDA party chairman Ad Lansink who was seen by the squatters as the person responsible for escalating the conflict). Together with Willem Baltussen, a member of the collective, he is currently working on a podcast about the ‘tambourine lady’, Oda Le Noble. She performed with a tambourine in the city centre for years. ‘I love cult heroes and “village idiots”. We are now in contact with Oda’s sister and plan to pitch our idea to national broadcasters.’

Battering ram for creativity

Verstappen really wants to play a role in the Nijmegen cultural scene. At music incubator De Basis, he initiated Geluidstafel, an evening held on a regular basis where musicians play songs to each other. ‘These songs are all works in progress, and the other musicians can give feedback on them. At Wintertuin, we’ve organised something similar for writers for years, under the name Literatuurnest. The musicians really enjoy getting together on these evenings – otherwise you’re always working on your own, in isolation.’

He and some friends are also organising Rocktober for the third time this year. The concept is simple: musicians are challenged to write a new song every day during the month of October. These songs are shared via Google Drive, and there is also a group app. That way, participating musicians hear from each other what they are creating, and they keep in touch with each other. ‘It acts as a battering ram for creativity. You don’t have time for writer’s block. It releases something. During previous Rocktobers, I ended up writing songs for Misprint, and I also collaborated a lot with other musicians. And if you don’t get a song out of it, you might learn something about recording, for example.’

With Geluidstafel and Rocktober, he wants to connect people and help develop the Nijmegen music scene. ‘A close-knit community is forming. People attend each other’s performances and help each other out, which is really nice. But I also benefit from it myself. I couldn’t manage to write songs for an entire month if I was on my own. I need the pressure from people around me.’

Three questions for Tom

What did you want to become when you were little?

‘Rubbish collector.’

Where did you go this summer? What kind of holiday did you have?

‘I went to Amiens (France) with my girlfriend and to Slovenia, Croatia and Germany with five of my friends. On holidays, I always try to fit in as much as possible. Lots of walking, visiting museums, long nights discussing crisp flavours, and little sleep.’

Who do you admire (within or outside your field)?

I can be shamelessly inspired by everyone around me. Mostly by people I create things with, everyone from Misprint, and four people in particular: Jens Bouwman, Willem Baltussen, Jelle Crooijmans, and Mart Bouwmans.

Verstappen won’t be kept away from his city. ‘I’ve never wanted to leave here. I love the left-progressive, anti-Randstad sentiment. I see myself as a Catholic atheist, with the Catholic sociability and atheist mindset.’

He points to the Stadsschouwburg. ‘There’s another wacky building. The foyer overlooks the Keizer Karelplein. It was probably a nice idea on paper, but because it is suspended so high above the ground, there’s also something vaguely elitist about it. It’s ugly, but I like that.’