Small electrical currents can help people with social anxiety

-

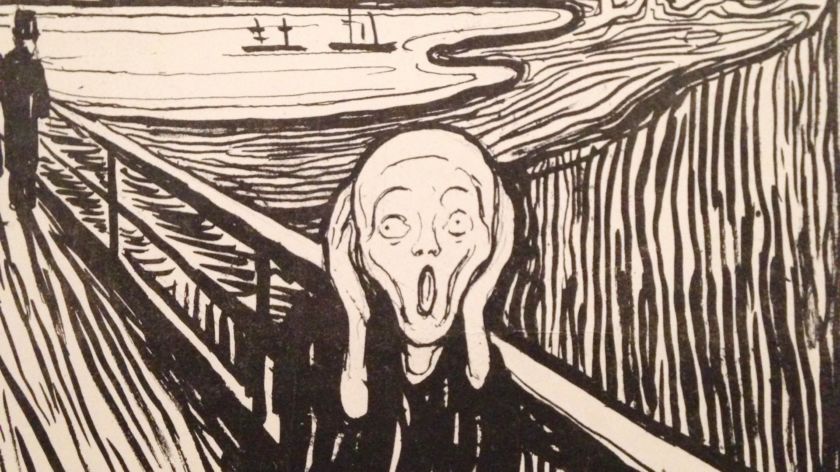

Bron: Wikimedia Commons (CC BA 2.0). Bewerking: Vox

Bron: Wikimedia Commons (CC BA 2.0). Bewerking: Vox

Small currents that you barely feel but which can help to eliminate anxiety? This may sound like a distant prospect but researchers at the Donders Institute have shown that it could work.

For some people it is a relief that restaurants are closed because of the coronavirus. People with social anxiety may spend days dreading a forthcoming meal in public, where everyone can see them. A new Donders publication in the scientific journal eLife shows that electrical brain stimulation may be able to help them in the future.

Emotional reflexes, such as the tendency to flee from danger, can be very useful. In an extreme form, however, they can lead to problems such as social anxiety. According to public health figures, some 600,000 Dutch people suffer from this disorder, women more so than men. For them, the fear of certain social situations, such as public speaking or going to a restaurant, can be so overwhelming that it disrupts their everyday lives because they start avoiding such situations.

Avoidance behaviour

Weak electrical stimulation of the brain can help suppress automatic responses of this kind, says brain researcher Bob Bramson, who conducted the study. These currents strengthen the communication between the prefrontal cortex – the executive area at the front of the brain – and the motor cortex, the part of the brain that controls movement. This then suppresses signals from the emotion parts of the brain (including the amygdala) that prompt avoidance behaviour.

In their experiment, Bramson and his fellow researchers at the Donders Institute simulated a situation that provokes an avoidance or approach response. Subjects (who didn’t suffer from social anxiety) were placed in an MRI scanner and shown pictures of happy and angry faces. At each photo, they had to either push a joystick away from them or pull it towards them. Bramson: ‘We know from other research that if you see something unpleasant, your automatic response is to push it away from you. That’s what happens with the joystick. It’s easier to push it away if you see an angry face than if you see a happy one. And vice versa: with a happy face, you pull it towards you more quickly.’

Reflex

The researchers saw these differences reflected in the behaviour of the 41 subjects. When subjects were instructed to pull the joystick towards them at the sight of an angry face, they did so more slowly and with more mistakes than when instructed to push the joystick away.

Interestingly though, if their brains were stimulated with small electrical currents during the task, they made fewer mistakes when performing a task that ran counter to their intuition. Bramson and his co-researchers concluded that the electrical stimulation made them better able to suppress their emotionally controlled reflex (‘push the joystick away when you see an angry face’). The MRI scans also confirmed that the currents had in fact affected brain activity.

Applause

How exactly does this work? Bramson explains: ‘We know from previous research that the prefrontal cortex and the motor cortex communicate with each other through certain brainwaves.’ Brainwaves are a form of rhythmic brain activity that is a little like two groups of people clapping in a stadium. If the prefrontal cerebral cortex wants to gain control over emotional reflexes, it claps slowly, at a frequency of about six times per second. The motor cortex claps a lot faster, about 75 times per second. They coordinate their applause so that it sounds “good”.’

The currents that the subjects received via electrodes on their scalp (tACS in the research jargon) reinforced this applause, as it were, making it easier for reason to conquer emotion.

Not permanent

We mustn’t think that anyone with a social anxiety disorder can rid themselves of it with a few simple electric shocks, Bramson warns. Firstly, the behavioural change only occurs during the electrical stimulation: the effect is not permanent.

And secondly, although statistically significant, the effects that were measured were small. ‘Of course, these were people without social anxiety, who make few mistakes. Patients with social anxiety have more problems with this type of task, and so we would expect the effects to be greater with them.’ Bramson, who has just completed his PhD, is currently setting up a follow-up experiment.

If you’re worried about scenes like in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, you can rest assured

Bramson hopes that in the longer term we will see the return of these electrodes to psychological practice – not to replace existing treatments, such as exposure therapy, but to support them. ‘With exposure therapy, people slowly become accustomed to the situation that causes their anxiety, which then reduces that anxiety. I hope that the familiarisation process will be quicker if this kind of stimulation is administered at the same time.’

If you’re worried about scenes like in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, you can rest assured. The electrical stimulation in the Donders experiment is not comparable to real electric shocks. Patients, often suffering from depression, who receive that form of therapy are given a much bigger electric shock that is designed to ‘reset’ their brain. Bramson: ‘At most, tACS causes a tingling sensation in your head that disappears after a few seconds.’

‘Also, the stimulation itself doesn’t affect your emotions; it just helps people to exercise control over their behaviour. It doesn’t mean that we can control emotional behaviour.’ In other words, he wants to point out that it’s very different from the crude electroshock therapy that finally silenced Jack Nicholson in the classic film.